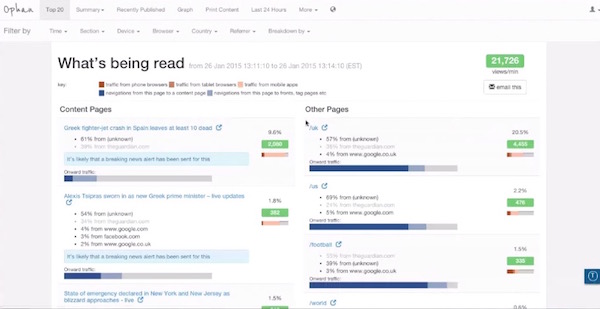

A little over a year ago, Katharine Viner, now the editor in chief of The Guardian US, had a question for the paper’s developers: Why didn’t Ophan, The Guardian’s internal analytics tool, work on mobile?

In short order, The Guardian’s developers built a mobile version of Ophan, and Viner has integrated the mobile analytics tool into her everyday routine.

“When I wake up, I lean over, check Ophan first, then check Twitter, and email, and personal things,” Viner told me earlier this week. “A lot changes a lot the time, and it can be quite unpredictable. Things do well that we don’t predict, things do badly that we think will do well, and you’re not really in the day unless you know what’s going on, and so having it on my mobile means I can look when I’m waiting for a train, it means I can just look all the time.”

Viner isn’t the only one who obsesses over Ophan. By design, more than 900 people across The Guardian’s newsrooms in the U.S., the U.K., and Australia have access to the analytics data. The idea is that staffers can take the information and use it to improve how their stories are performing and provide additional information they think would be relevant to readers.

A few weeks ago, for example, The Guardian noticed a spike in traffic to a story from February 2013 about former Navy Seal sniper Chris Kyle’s death. The piece was receiving renewed interest because of the release of “American Sniper,” the new movie based on Kyle’s life. To capitalize on that traffic, The Guardian re-promoted the nearly two year old article. (Though some Twitter users were confused why the story was tweeted out as if it was new.)

Former Navy Seal sniper Chris Kyle shot dead at Texas gun range http://t.co/8W5blMGigV

— The Guardian (@guardian) January 9, 2015

The Guardian wants staffers to use Ophan to make even the slightest of changes to stories or locate sources of traffic. Say someone notices an influx of traffic to a story from Reddit or that users are lingering longer than usual on a story, the staff can then tweak the headline to capitalize on that social platform or add in new links to the story to give those users more information and increased exposure to Guardian content.

“Everybody can see the results that they’re having,” Mary Hamilton, the assistant editor of Guardian US said. “So a lot of people involved in the production process, so if they make a change to a headline, or if they add a link or if they add something on the front, they can now actually see the results that that’s having in real time. They can test out a gut instinct and see what happens, rather than just flying purely on that instinct.”

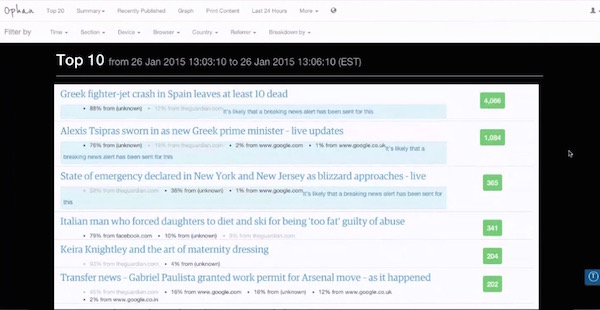

In order to get people to use the tool, The Guardian needed to make it easy to use and understand. The company’s developers built bookmarklets that let users paste a link and be taken to that page’s Ophan information, which shows users how a live Guardian page is performing at the moment. The tool only analyzes a week’s worth of content and focuses primarily on attention time and page views because “that’s the thing everyone can understand,” Hamilton said.

This approach isn’t uncommon among some legacy news organizations. NPR last year developed its own internal analytics tool along the same lines as The Guardian’s, which lets all staffers get a better sense of the data surrounding their stories. Other news organizations are emphasizing increased use of analytics. In its innovation report last spring, The New York Times called for better cooperation and communication between the newsroom and its “Reader Experience” departments of R&D, product, technology, analytics, and design.It’s those types of relationships, however, that has allowed The Guardian to continue to develop Ophan since it was first created out of a hack day in 2011 by Graham Tackley, The Guardian’s head of architecture. The audience engagement and development teams constantly discuss improvements to the tool. Whenever an editorial staffer first begins using Ophan they typically suggest new features to add — much like how Viner asked for a mobile view of the site.

“We just had a consistent and really open process where editorial feedback was fed back regularly,” Hamilton said. “The development has always been very agile, so we always have gone toward the minimum possible thing and then iterated on that thing, rather than waiting for it to be beautiful and built out perfect.”

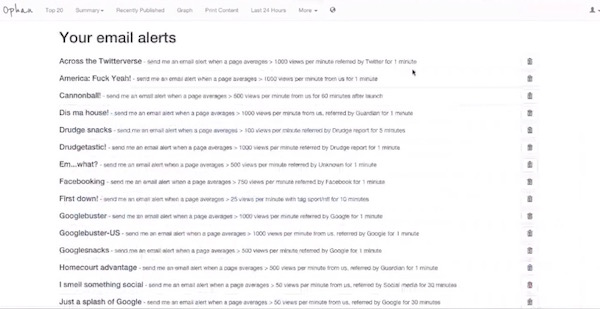

When it first launched, Ophan only held 3 minutes’ worth of traffic, but over the years The Guardian has added more functionality, so editors can examine everything from a single article, to a section front, or the entire Guardian site. Among the more recent additions to Ophan is a function that will email staffers when certain traffic conditions are met, Ian Saleh, The Guardian’s audience development editor explained, showing off his own email alerts.

Among his long list of alerts, Saleh will get an email when a page on The Guardian US site gets more than 1,000 views per minute via a referral from the Drudge Report for at least one minute or when a page gets at least 500 views per minute from an unknown site for a minute or more.

Saleh said this was a good way of simplifying the data and making sure editors and reporters are seeing the information that’s important and relevant to them.

“We know that everyone in the newsroom has a lot to do, and we know that we could build the most amazing tool in the world, but if a reporter or editor can’t access the information in Ophan without spending 20 or 30 minutes within the dashboard or being an expert, we know that’s a lot to do day in and day out,” he said.

Another experimental feature on Ophan is a live-updating ticker of what Google search terms have brought people to Guardian content. Because of the way Google is set up, The Guardian only receives between 10 and 20 percent of the search terms, but even then Hamilton said the information has been illuminating.

“It’s a really interesting way of humanizing Google traffic,” she said. “When we’re looking at some of the culture changes that have to occur in a newsroom that’s adjusting to this kind of data, getting people to understand that every single one in that massive basket Google traffic that you can’t really see into is actually just a person typing something in and hitting the Guardian.”