Editor’s note: On Monday, Apple is expected to formally launch the Apple Watch, which will go on sale next month. As the company shows off what developers have built for its smartwatch, perhaps we’ll see something we didn’t when it was first announced last fall — some indication of how news might fit on the new device.

Jack Riley, head of audience development at The Huffington Post UK, spent the past month here as a Visiting Nieman Fellow, studying that very question: How should news organizations think about the Apple Watch, Android Wear, and the new class of wearables some predict we’ll all have on our wrists soon? What are the opportunities, the risks, and the challenges?

I’m pleased to share his report with you — I hope it’ll be read widely among the people making wearable-related decisions at news companies worldwide.

Any Apple product announcement prompts an outsized response, and the Apple Watch was no exception. Reaction from consumers was typically polarizing; for the news industry, the response was a typical mixture of excitement and fear at the prospect of molding a meaningful experience for users on a whole new platform — not to mention the challenge of creating an even shorter news experience that threatens to “make tweets look like longform.”

Of course, wearables in general and the smartwatch in particular weren’t invented in Cupertino. But the impact of the Apple Watch was such a certainty that, even before Tim Cook had stepped onstage to unveil “Apple’s most personal device ever,” I’d begun to formulate this research project on the effect that new smartwatches would have on content businesses. In the past month, I’ve spoken to many of the people figuring out wearable strategy at publishers including The New York Times, BuzzFeed, the Financial Times, The Washington Post, the BBC, USA Today, and Circa — as well as others outside the news industry whose alternative experience may help point the way for media companies. In this report, I try to cover the potential editorial, product, and commercial implications of the mainstream uptake of wearables broadly and the smartwatch in particular.

Alongside fitness trackers from companies like Jawbone and Fitbit, the smartwatch is projected to be the key wearable product category to grow over the next few years — particularly since Google’s decision to slow development on Google Glass. Compared to a headset, the wristwatch has the advantage of a hundred years of mass market adoption. Even the act of playing with a watch obsessively has a rich history. Here’s Samuel Pepys in 1665:

But, Lord! to see how much of my old folly and childishnesse hangs upon me still that I cannot forbear carrying my watch in my hand in the coach all this afternoon, and seeing what o’clock it is one hundred times; and am apt to think with myself, how could I be so long without one; though I remember since, I had one, and found it a trouble, and resolved to carry one no more about me while I lived.

Pepys’ £14 device, a gift from a scrivener that was “a greater present than I valued it,” might seem a world away from the new generation of smartwatches, which compress smartphone technology into a familiar form factor. But his mixed feelings about a new gadget were notably similar to the reactions some of my interviewees had to their early experiences with smartwatches. At first, the novelty of a new device can elicit strange or jarring experiences, though they can grow to be useful more quickly than you might imagine. Andrew Phelps, senior product manager for iOS at The New York Times (and a former Nieman Lab staffer), described how his first smartwatch experience made his “whole body started vibrating” when he started receiving notifications on multiple devices at once:

Pepys’ £14 device, a gift from a scrivener that was “a greater present than I valued it,” might seem a world away from the new generation of smartwatches, which compress smartphone technology into a familiar form factor. But his mixed feelings about a new gadget were notably similar to the reactions some of my interviewees had to their early experiences with smartwatches. At first, the novelty of a new device can elicit strange or jarring experiences, though they can grow to be useful more quickly than you might imagine. Andrew Phelps, senior product manager for iOS at The New York Times (and a former Nieman Lab staffer), described how his first smartwatch experience made his “whole body started vibrating” when he started receiving notifications on multiple devices at once:

The first experience I had was a sort of revulsion, because I always had something competing for my attention. Suddenly I’m in a meeting, and whereas the phone in my pocket is not a distraction, the watch is always just out of view and lighting up and buzzing.

Once you’ve dealt with your personal reaction to having a gadget physically attached to a wrist, you still have to handle how others perceive it. One common social stigma described to me by Joey Marburger, director of digital products and design at The Washington Post, is something I and many others have experienced:

I was one of the first people to get the Pebble smartwatch. My logic was like: I can silence my phone and I’ll tailor notifications that come to my watch. I don’t have to use my phone in a meeting, or pull out my phone and be rude — I’ll just check my watch. What I learned very quickly is I was being more rude, because it looked like I was constantly checking the time.

While checking your phone is still not acceptable in all settings, it still beats the palpable sense of impatience associated with raising your wrist. Checking your smartwatch in company is going to require a new set of social norms to become natural and commonplace.

While checking your phone is still not acceptable in all settings, it still beats the palpable sense of impatience associated with raising your wrist. Checking your smartwatch in company is going to require a new set of social norms to become natural and commonplace.

Confusing what’s essentially a miniaturised smartphone with a conventional timepiece is an awkward behavior partially caused by these early smartwatches’ skeuomorphism, the design tendency to create technologies that mimic analog or real-world products in order to make themselves easier for users to understand. Eventually though, one imagines that, as Apple has done before, the idea of a watch as a reference point for these devices will grow less and less relevant. Before that happens, though, publishers will have to figure out how to make a new category of products work for them and for their readers.

The first key question for any publisher considering a wearable product is the scale of the opportunity. How many of their current (or potential) readers will even have smartwatches?

Alex Walters, who led development of the Financial Times’ fastFT wearable app, described a familiar scenario for content companies: weighing finite resources against the new opportunities available to them: “We would love to make apps and content provided for all kinds of different weird and wonderful devices, but it’s just not realistic to serve every corner of the market…so we have to establish where our users are.”

For large publishers whose mobile audiences are likely in the tens or hundreds of millions, smartwatches may seem like a small market for quite some time. The biggest player is, of course, the Apple Watch, set to be released next month; conservative sales estimates put it at 10 million units sold this year, with Apple reportedly having ordered more than 5 million units for the first run of the device; most analysts are guessing higher, at between 20 million and 30 million sold in 2015.

Recent new Apple product categories have doubled (in the case of the iPad) or tripled (iPhone) shipments in their second full year after release, meaning it’s not unreasonable to imagine a potential 90 million Apple Watches on wrists globally by the end of 2016. The “attachment rates” analysts are using for Apple Watch sales estimates — the share of the total addressable market, which is anyone with an iPhone 5, 5C, 5S, 6, or 6 Plus, who would buy a watch — range between 5 and 10 percent.

How about outside Apple? Over 2015, analysts at CCS Insight estimate 5 million non-Apple smartwatches will be sold, the vast majority of them running Google’s Android Wear operating system and from companies like Sony, Samsung, LG, and Motorola. That would be a leap upward: Research firm Canalsys claim that in the six months from Android Wear’s release to the end of 2014, only about 720,000 devices were shipped, with the bestseller being the round Moto 360. Over the same time period, Pebble sold 550,000 devices, taking the total worldwide shipments of the Pebble and Pebble Steel models to 1 million by January 2015, almost two years after their release.

CCS analyst Ben Wood argues that the Apple Watch’s reliance on an accompanying iPhone and its higher price point (starting at $349) could help lift Android Wear devices:

We also think though that there’s a rising tide, so Apple Watch will undoubtedly help sales of other products, predominantly Android Wear, because if you don’t have an iPhone, Apple Watch isn’t useful to you, but if you want to be with the cool kids and you have a two-year contract on an Android phone, then you’re probably going to go and get an Android Wear watch. Bear in mind that Android Wear is going to be a lot more affordable than Apple Watch.

Jeff Malmad, managing director at media and marketing group Mindshare North America, agrees that “when Apple Watch comes out, it helps the industry as a whole.”

Outside of Apple’s walled garden, it seems unlikely that smartwatch operating systems will divide as neatly into “Android, Apple, and everyone else” as the smartphone market has. Manufacturers including Asus, LG, and HTC are working on alternative smartwatch OSes, perhaps keen to avoid extending Google’s outsized influence on the non-Apple smartphone market. (Samsung’s Gear S device, for instance, runs its Tizen alternative OS.)

The first wave of users in any new product category is not necessarily representative of its larger eventual user base. But beyond classic gadget-happy early adopters, smartwatches will have another group of 2015 buyers: fitness enthusiasts. With fitness tracking positioned as a “killer app” for the first wave of wearable devices, Gartner predict sales of fitness-based wearable devices will fall from 70.2m global units in 2014 to 68.1m in 2015 despite growing demand, as users migrate from screenless wearable devices like the Jawbone UP and Fitbit to smartwatches. Apple CEO Tim Cook has drawn attention to the Apple Watch’s ability to combat a sedentary lifestyle with notifications to urge physical activity, saying “Sitting is the new cancer.”

Will news apps drive smartwatch uptake? None of the people I spoke with felt that news will be the individual incentive for consumers to purchase a wearable device in the way that fitness has been. As the Post’s Marburger put it to me: “No one’s going to buy a smartwatch because they get better headlines from one news source.”

The Times’ Phelps also sees an opportunity in this early adopter and pro-fitness profile for publishers to reach a highly valuable segment of their audience: those who are both wealthy and young.

The watch is truly a luxury device, because the watch requires a phone — for every watch that Apple sells they’ve also sold an iPhone. The overlap in the Venn diagram of those two groups is not very big. “Young and techie” and “lots of disposable cash” tend to be two very different audiences. So I’m left still wondering how this thing will sell. Now, if you can reach both of those at the same time, I feel like that’s the sort of golden ticket, right? You’ve found the most desirable users, because they’re young and can grow old with your brand, and they have money to spend.

I found plenty of reticence about the challenge of developing for the first generation of wearable products, with Marburger describing the problem as most devices available at this point being “too expensive or not connected enough.”

For all of wearables’ potential in their own right, the most salient technological shift the smartwatch could cause for news companies might be the shift to multi-device products designed to work seamlessly across multiple platforms. On both the Apple Watch and Android Wear, the Bluetooth link between the phone and the watch is essential to their operation, both for connectivity and processing power. The potential goes much further than that technical link, according to Robin Pembrooke, head of product at BBC News, who sees real possibilities in tying together products across devices so that “wearable devices interoperate with your services, from not just news providers but a wide variety of people on different devices.”

Part of that value is because, as many people expressed in the course of my interviews, the watch is not going to be the focal point for consuming content — even for publishers who’ve invested lots of effort in thinking about how they deliver it. “The wearable screen size is not great for reading,” says Julian Richards, who leads mobile products at Gannett, parent company of USA Today. “The device was never meant for lengthy interaction.”

Pembrooke puts this in terms of identifying where the payoff of wearable content really exists: “On a watch, it’s nice to get those kind of short updates, but you’re primarily getting into a ‘save for later’ or ‘share’ mentality…Your gratification to consume the rest of the content comes later.”

That model can be especially appealing to subscription publishers like the FT, who can offer a smartwatch experience as a useful benefit to an all-access paid customer, tying multiple services including wearables into a more coherent cross-platform experience for users. Walters described a theoretical model where reading the Financial Times through the day is a “seamless experience”:

The most interesting thing for publishers over the next few years is going to be how we link together our experience of our publication across multiple devices. To give you an example: I start reading my in-depth analysis page on FT.com in the morning, but I then get on the train and I want to carry on reading on my phone, or I get into the car and I want it read to me aloud.

The less friction we create between devices for users, the more they’re going to default to your brand, your content, because it’s an easy and beautiful experience that doesn’t demand their time and effort. Publishers who do that really smartly are going to be the ones with high engagement.

Historically publishers…have built products for individual devices. Now the next step is to say: Which are the most important features of these devices to us?…and work out how we can create experiences across them.

Building for multi-device experiences also hinges on acknowledging that wearable development is less about one particular device as it might have been in the past for the iPhone or iPad, says Joey Marburger. It should be more about building in device flexibility: “There will always be new trends…but how do we make sure that our content is flexible enough to be displayed in any type of wearable so that when the next wearable thing comes along we’re ready for it?”

This trend for interoperability extends to device design. The growing screen size of smartphones, typified by flagship Android phones and the latest iPhones, can be interpreted as an acknowledgement of the potential for wearable technology to augment smartphone usage, since “the iPhone 6 Plus makes much more sense if you have the watch,” as venture capitalist and investor Taylor Davidson tells me. (The benefits of a larger screen are balanced by the devices’ more awkward size; a smartwatch could be a window into a large smartphone without the hassle of removing it from a pocket or purse.)

“A wearable is an extension of a greater experience,” Matt Galligan, CEO at mobile news startup Circa, says. “That could be a computer and wearable, or it could be a tablet and wearable, or it could be a phone and wearable. These are extensions. These are not meant to be replacements for consumption experiences.”

To fully assess the impact of the smartwatch on smartphone usage would require a lot of user data that, for now at least, isn’t available. I heard two opposing theories in conversations around this interaction. One argues that the proliferation of wearables would diminish smartphone usage — since salient information will be instantly accessible on a wearer’s wrist. The other opposing scenario posits that the immediacy of smartwatch alerts will make users engage even more often with their personal devices, including the smartphone.

But Alex Markowetz, an expert in smartphone addiction at the University of Bonn, cautioned that the idea that wearables will help users moderate their device usage is predicated on the myth that smartphone usage has a rational basis. His work has found that interactions with personal devices are defined far more by habitual behaviors than logical ones: “Smartphone usage is actually habitual. It’s not a conscious, deliberate decision.” (Think of how often you find yourself with your phone in your hand without a specific purpose in mind — or even an idea of how it got there.) For news publishers, this question might have an impact on the kind of apps to build — editorial products designed for constant checking behaviors or for notifications that limit users’ habitual engagement with the news in favor of a push-based model.

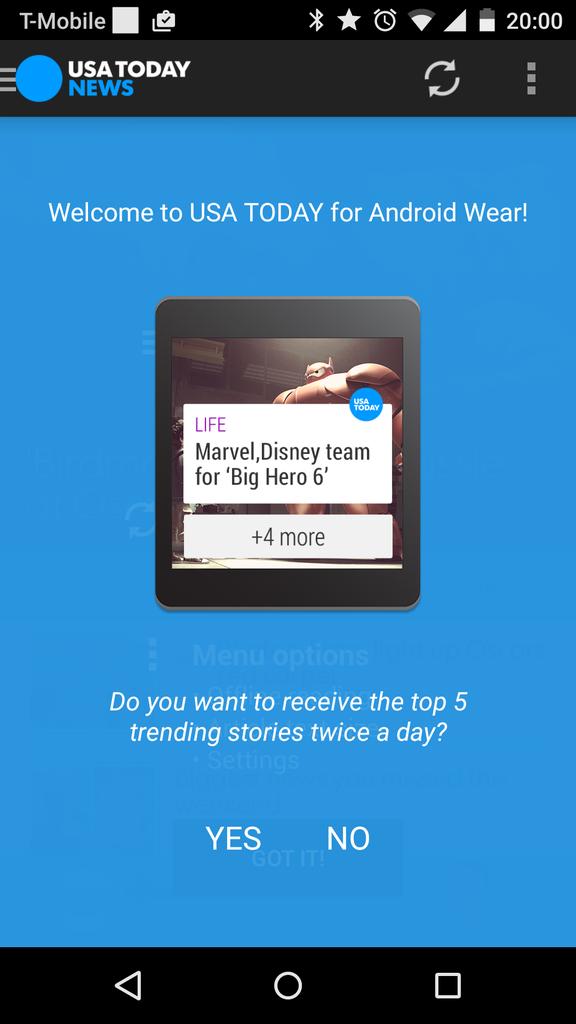

USA Today is one of the few publishers to have already released a product for smartwatch — an Android Wear extension to its Android app. Richards described how their first wearable app came about and the motivations behind it:

USA Today is one of the few publishers to have already released a product for smartwatch — an Android Wear extension to its Android app. Richards described how their first wearable app came about and the motivations behind it:

The main application is a twice-daily delivery of the top 5 stories, based on user traffic. They are downloaded at times the user sets and provide a quick overview of what’s generating the most interest on USA Today right now. The user can swipe left on any one of the story cards to either open and read directly on the phone or else to save for later reading — there’s a new “saved articles” area to hold these.

From users’ perspective, we’re offering an extremely simple way to stay up-to-date on what’s “most important,” without waiting until they normally sit down to read the news or forcing them to dig out their phone/tablet and check headlines. We know that news consumption tends toward frequent checks throughout the day, keeping up with the latest developments. The Wear app lets them do this in seconds.

From our perspective, we’re placing our brand and content on a screen that is constantly checked throughout the day. This provides yet another opportunity for users to engage with us — outside the existing news-reading times — ideally resulting in increased visit frequency.

Though wearables are a nascent category, with limited immediate potential to impact audience and revenue, monetizing new platforms is a long-term concern for publishers, whose business models are already in a constant state of flux. Outside of news, the advertising industry is beginning to see significant commercial potential in wearables as a marketing channel, given the immediacy of the smartwatch experience and the volume and quality of novel data wearable sensors are likely to generate. Jeff Malmad told me that Mindshare in particular see wearables and the Internet of Things as a distinct opportunity on the same scale as prior mediums: “We think about the different waves of digital advertising. We think there was the first wave, that was desktop; the second wave, which was the mobile device; and the third wave, which we believe is wearables and the internet of things.”

But commercializing wearables won’t just mean transferring existing marketing models to a watch, Malmad argues:

We’re not talking about sending a 30-second video clip to a watch. We’re not talking about sending a banner to a watch. What we’re talking about is how we provide an additive experience to the consumer in a way that they’ve opted in for, or done in a way that’s not highly intrusive.

For publishers, the risk of missing out on a new platform is real. “Given that we, the industry, practically haven’t figured out how to monetize mobile, I’m a little concerned about wearables,” the Times’ Phelps says.

The multi-device nature of wearables’ rise may differ qualitatively from mobile disruption, though. Mobile traffic usually rises at times of the day that desktop traditionally didn’t cater to, like early morning and evenings. Wearables will exist alongside mobile content consumption, since the devices are intended, at least in the near term, to work with an accompanying smartphone. Publishers may be looking to smartwatch alerts to drive attention into mobile experiences — where monetization is, while still fraught, better understood.

The biggest issue with display advertising on wearable products is obvious: screen size. (The largest Apple Watch screen is just 42 millimeters tall.) While many publishers I spoke to didn’t rule out this opportunity — “never say never, because advertisers find a way to get their messages on every damn screen in the world,” as one put it — few thought it was likely to work well in the near term. According to Maik Maurer, chief technical officer of speed-reading developer Spritz, that kind of transposition is typical of publishers’ attempts to adapt to new platforms: “People will just try out the way they’re used to advertising and content presentation in general, like they used to do it on smartphones. They will try it on watches and they’ll think ‘it doesn’t work’, because the environment has changed.”

Setting aside traditional display advertising, the opportunity for publishers to derive revenue from wearable devices is likely at first to be limited — but three possibilities stood out in my interviews.

First, there may be native opportunities for publishers to generate content used in brand-led applications, from which they could derive direct content licensing or partnership revenue from a brand. Delivering relevant content and “surround[ing] it with a brand,” as Malmad described it, may open up new opportunities. Imagine a Budweiser-branded nightlife guide that uses Time Out content to furnish location-specific smartwatch alerts with star ratings of local bars when a user is traveling around a city on a Friday or Saturday night.

Second, the wearable device is potentially a powerful channel to activate smartphone use for ad-supported publishers, where business models are starting to mature. Even where an alert is not translated into opening content on a smartphone device, publishers may benefit from the positive effect of building product loyalty that keeps a user engaged with a brand for future interactions.

Third, subscription publishers may find that wearable products are an additional service to boost the perceived value of multiplatform or mobile-only subscriptions. Both The New York Times and the Financial Times indicated to me the advantage they perceive their mixed ads-plus-subscription models to have on wearable platforms. “As it stands, at least with Apple,” Phelps told me, “the watch apps are directly tethered to phone apps and require a parent phone app. And so a pricing strategy that makes sense for the phone app may just extend to the watch.” For financial and sports publishers in particular, the timeliness of their alerts is key to their perceived value, and as such they may represent a greater opportunity than in traditionally lucrative content verticals like lifestyle and travel.

Publishers I spoke with are not yet worried about the longer-term effects of the potential migration of attention from smartphone platforms to wearables. In the meantime, traditional display advertising directly on smartwatch devices themselves may well yet prove viable, according to Taylor Davidson, particularly when you consider the history of advertising on new platforms, which typically scale first and monetise second:

If you look back over time, advertisers said ‘We’re not going to advertise on the web,’ ‘We’re not going to advertise on Facebook,’ ‘Facebook makes no sense,’ ‘Twitter makes no sense,’ ‘Snapchat makes no sense’…It doesn’t make sense based on what you see today. But if you have hundreds, millions, or billions of people using it, then you’re going to figure out a way.

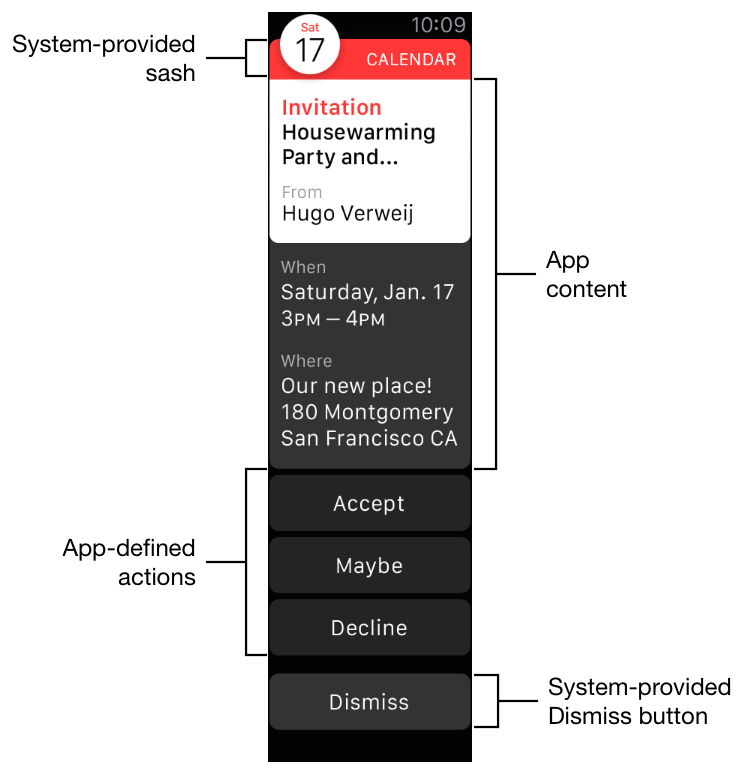

Since consuming content of any reasonable length on a smartwatch is difficult, the key focus of any wearable content product is likely to be push notifications. Notifications have been growing in usage and prominence since their introduction in iOS3 in 2009. The New York Times’ Andrew Phelps noted how exceptional they are as a medium:

The New York Times reaches about 15 million devices with our breaking news alerts, which is just a crazy number. No communication medium in history has ever allowed us to reach that many people all at the same time, maybe with the exception of television. I mean even if our Twitter account had 15 million followers, only, what, 2 percent of them would see a tweet at any given time. We have this great power in being able to say whatever we want to all of these people at a moment’s notice — and so with that comes a lot of responsibility.

And unlike television — with the exception of something like the Emergency Alert System — a push notification can change what you’re doing at any time. Everyone I spoke to believes the notification to be the primary type of user interaction on smartwatch devices.

On the Apple Watch, there will be two types of notification. One is a Short Look, that comes up when an app has something to tell you, with just a glance at that information. Then, there’s a Long Look, triggered if you leave your wrist up with the notification on, which will display more information associated with the notification. On Android Wear, the notification either sits in the background where you can look at it any time or alerts you and lets you tap on it to expand or swipe for other options.

Most news organizations using push notifications on smartphones use them to send breaking news alerts, often undifferentiated by topic or user preferences. Almost everyone that I spoke to said they see the smartwatch as an ultimatum on this model of notifications. The BBC’s Pembrooke described the problem with reference to the BBC News app:

The pitch that [Apple] are making as the top-level proposition is that it’s a much much more personal device. And therefore one of our issues with notifications at the moment for us is that at the moment we don’t have much personalization in notifications. [When] we send a BBC News alert, it goes to everybody — no matter what time of day or night it is, wherever they happen to be, and regardless of whether or not they’re interested in that particular topic or not.

Apple is emphasizing the “personal” aspect of the Apple Watch; executives used the word 19 times in its introductory announcement. This thematic focus has certainly filtered down to publishers, who overwhelmingly cited both personalizing content and using a more personal tone as central to developing successful smartwatch content. Since the Apple Watch is “such a personal device, it makes perfect sense to be pushing more personal alerts,” Phelps says. On wearable products, “personalization is a given,” according to USA Today’s Julian Richards; at The Washington Post, Marburger said “maybe a wearable strategy is personalization overall”; Alex Walters at the Financial Times described personalization as “the most important factor” in a wearable content strategy.

Many publishers will face both technical and resource challenges in personalizing their content for wearable products. Besides being able to rely on a user’s iPhone or Android phone to build a rich personal profile of users, new smartwatch devices have their own suite of sensors to assist with this process. For the first part of its lifespan, the wearable was defined by its sensors, since Fitbits and Jawbones used them to track your fitness behavior. Despite some of the health-tracking aspirations having been pared back in the Apple Watch, most smartwatches will still have microphones, ambient light sensors, accelerometers, and heart rate monitors. Some have GPS and mobile reception built in, while other rely on the attached phone for that data.

USA Today’s Richards notes that these “devices are packed with sensors, carrying a detailed awareness of users’ lives. They could, for instance, enhance a story on sedentary lifestyles by showing how you, personally, measure up.” Pembrooke sees a path for the BBC that relies more on location data than the biometric awareness of smartwatches:

The more relevant use cases are less around data garnered from a wearable…similar to pulse rate than data you can garner in terms of where someone is — and focusing breaking news or local news alerts based on location rather than that kind of personal data.

Location could be critical, since even though most publishers find that most mobile usage is in the home, it could be that wearables deliver the truly mobile experience we once expected of smartphones. According to investor Taylor Davidson, the opportunity can be thought of by asking: “What parts of our day do we not have a phone in our hands?”

The Apple Watch at launch will have only very restricted hardware access for developers, so it might be that we don’t see news products that take advantages of those sensors for some time. But Kurt Mueller, a developer I spoke to at Concentric Sky — a development company that’s created products for National Geographic and the UN — thinks that Apple will unlock them as the product matures. Just as with the original iPhone, the toolkit will be opened up so that developers can eventually tie news products in with the richer picture they’re getting of their readers. That could mean apps that send you post-workout meal recipes, or that tie into your daily routine — knowing when you’re talking a walk around the block to send you an update on a story you’re interested in, knowing not to push you breaking news alerts when you’re out for a run, or knowing that when you’re sitting down at work, it’s not a great idea to distract you.

Those last examples might be key, since they’re built on a concept of “negative space” in news publishing, which current digital products don’t acknowledge — knowing (and acting on) when not to interact with someone. Alex Markowetz, whose work on smartphone addiction emphasizes the dangers of device addiction in the modern knowledge worker economy, described the issue like this:

The next feature of the phone [should be] a feature that lets me interact with the phone less frequently. The phone that helps me leave the phone alone. Because I’m a knowledge worker, that’s how I make my money — by thinking — and I don’t want to be interrupted.

For publishers already putting personalization front and center via active or passive cues from readers, the reward may be an easier transition to the new model. Circa’s Galligan sees its follow-a-story model (which allows users to select stories they see as important) as a boon for building wearable products that might feature this functionality most prominently: “In our case, the service model, on top of the ability to keep people in touch with the things that they care more about and do so in a way that gets them what they need and then gets out of the way, is a major advantage of ours.”

There are challenges in developing this idea of relevance though. Here’s how Andrew Phelps expressed them to me:

Personalization alone is fraught with problems. When you recommend something to someone using an algorithm and they don’t like that recommendation, you’ve lost them. So now you combine that with the fact that you’re interrupting their day on yet another device and it’s really a minefield.

We also have to tread lightly because nothing is more terrifying than the simplicity with which a user can disable alerts from this provider forever, and that the biggest and best form of retaliation is in the user’s hands.

For Noah Chestnut at BuzzFeed News, the notification represents an opportunity to adapt the tone and voice of a publisher: “Notifications are difficult. It’s a new format and it’s a new form that has this sense of immediacy. But also because the most common form of notification is a text message, they can also be silly, they can be light, they can be personal.” Noah cited the impersonality of mainstream breaking news alerts as a drawback for publishers looking to extend their notification strategy to wearables.

The alternative is to make notifications more like the content they coexist with on a platform. Since they sit alongside text messages, their tone could be more social and friendly. Publishers with a more traditional voice will find it more difficult to adapt than publishers like BuzzFeed and Vice who’ve already cultivated this social tone.

However it’s achieved, being relevant, personal, and glanceable are the three key factors in creating appropriate and successful wearable content. As Chestnut described it to me, publishers will have to move beyond “I just receive and consume.”

Without a dedicated editorial team generating or repurposing content specifically for wearables, publishers may find their hands tied by their current content formats — unless, perhaps, like Vox’s card stacks navigation or Circa’s atomization, they’ve already invested effort in building more wearable-appropriate formats. Circa CEO Matt Galligan sees their principle of atomization as an advantage over more straightforward summaries in terms of delivering content modularly on smartwatch:

There’s an interesting challenge when it comes to summaries and evolving news, in that when a story that you’re paying attention to continues over time, summaries get worse and worse over time — because there’s only so much that you can do in the way that everybody writes articles today. You’re writing for two audiences: the audience that has never seen this subject matter before and the audience that has. You have this issue of background. When you do a summary, you continue to have those issues of background — it’s just now you’re working in less space.

So there are certain challenges that would come up otherwise, and I think for our purpose, atomization was always the choice — because we always knew that if a reader wants to be continually informed, then we would have that opportunity and be able to provide that without some kind of condensed, watered-down version of the facts. So not only have we been prepared for this for some time, we’ve been producing [atomized content], which is a very unique and distinct advantage, because otherwise your best bet is summaries.

For publishers using more traditional formats, the task becomes one of content selection. “The main challenge is working out what’s the most important information that we can put on a screen of that size to our users, [and] what will they find most useful to have on that device,” the Financial Times’ Alex Walters says. Even so, he emphasizes that more user feedback is needed before settling on any particular content experience. Even content experiences that might seem too long at first glance — like putting full articles on a watch screen — could be under consideration “if the user experience tests well.”

In the short term, repurposing content is likely to be the only scalable approach open to publishers looking to create wearable products, the Post’s Joey Marburger says. “If you just try to take stories that maybe do well on mobile and make them feel smaller or more digested and put them into a watch interface, I think that’s like a very short-sighted strategy,” he says. “But unfortunately, that’s what could work best for most publishers.”

One consistent belief among interviewees was that the right content formats for wearables will appear over time. “Every time a new sort of media comes out, people usually decry it for being dumbed down or not being good enough to create rich content,” Taylor Davidson notes. “Yet people always find a way to create really cool things with really dumb and simple tools.”

One opportunity for traditional content companies is for service-based content in areas like weather, travel alerts, and finance information — though the potential for specialist-produced apps or OS-level intervention is significant. Describing, as an example, a smartwatch subway travel alerts product, Marburger laid out the challenges:

If I’m walking onto the platform and I have a watch that buzzes and says there’s a Red Line delay, that’s handy, but do I know that came from the Post, or Yahoo, or the actual Metro company themselves?…That’s something that we could do, but that’s very specific. Are we going to be able to scale out across the entire world for that? No, because Google already does it, and Google will do it on devices like that. So it could be fun and cool, and we [could] try it out and a couple of readers like it — but that’s not really a strategy.

For USA Today’s Android Wear app extension, the opportunity is as much about catering to the user experience of checking the time as it is about alerting them to new content. “The sweet spot right now is satisfying the user’s need to constantly be ‘in the know’ — ideally before anyone else,” Julian Richards says. “[Android] Wear can do that in a far less intrusive way than normal push notifications: Users naturally glance at watches all the time and can get a little hit of news as a bonus.”

These new platforms and sensors create a wealth of opportunities for news publisher to innovate with creating and delivering content to users. The majority of publishers I spoke to described a first wave of content products primarily based around notifications, but delivered in a more personal tone and more relevant than the normal breaking news alerts delivered by smartphone apps. But in the course of our conversations, many potential concepts for future products came up.

Andrew Phelps at The New York Times sees the opportunity to be personal extending to establishing more of a relationship with readers through timed alerts:

Since [the smartwatch] is such a personal device, it makes perfect sense to be pushing more personal alerts. One example might be saying “Good morning!” to the user as soon as the watch detects motion and providing a link to a roundup of the day’s news or some sort of a briefing. Another one might be recommendations of articles we think you might like that are doing particularly well on social media right now.

Joey Marburger at The Washington Post agreed with that idea of figuring out a personal experience that could replace the habit of a “newspaper dropping on your doorstep on the morning.” He also described the potential in notifying people of content that’s not necessarily suitable to be consumed on the smartwatch but could extend to the smartphone:

One idea could be that we’re not going to send quick headlines like Yahoo News Digest — we’re going to maybe send one push onto your watch when we know that you’re in a very specific scenario. Say I’m on my way home from work and I get a story that’s just a randomly selected feel-good story. Because that’s when I want to play a game — I don’t really want to think; my mind is busy, I’m already overloaded. Here’s a good story about a guy that rescued some dogs.

BuzzFeed’s Noah Chestnut also expressed the idea that only pushing straight news content would be unnecessarily limiting: “With a watch, I do think that opinion has a different role to play than it may have with a push alert on a phone.” Content delivered by news publishers could be intended to start conversations and waves of sharing rather than just inform a reader or encourage them to read content on their phone.

Jeff Malmad described a few scenarios where location awareness could be the key factor in determining what content gets push to a user and when:

When I’m walking into a store, I could get a push notification to my phone as well as my watch, giving me information as related to that product and recipes around that project that I should swipe and learn more about. So location is critical, as well as timing…With the smartwatch, it just makes it more imperative, because a lot of times you’re not going to have your phone in your hand at all times.

The store example would involve using editorial content to support what might be a commercial experience. As such, the potential for publishers to provide contextual content to non-news products may constitute a native advertising opportunity — a chance to monetize content on wearables that publishers would not be able to pursue on their own. Malmad described another content-enriched experience where location is the basis of the product:

Take a golf magazine and a golf site, and I’m on a golf course. There’s a program that this golf company does where being able to track historically where Arnold Palmer hit a 275-yard birdie. So we can deliver a really interesting story that’s pushed to your watch. It’s very technical, but it brings it to life. We’re taking all the data that exists and we’re able to tell stories around that.

The use of location as a content trigger would also open up opportunities in travel and history journalism to provide rich “guide” experiences. Though using location to tailor content delivery is possible on smartphones (and already used, for example, by Breaking News), the lower friction of a wearable device could present the opportunity to build new lighter notification experiences that notify the user more frequently. Joey Marburger at The Washington Post described the opportunity: “Singular bits of information that are very proximity-oriented is what will succeed in the wearable space.”

The publishing industry’s most recent phase of growth has been defined by the use of data to optimize content and product. One potentially tricky issue for publishers developing for the first generation of wearables is the lack of data available — both in terms of news consumption specifically and product interactions generally. Without usage data, Phelps told me, it’s impossible to validate product ideas, saying that as a publisher, “we have to step back and say, ‘Look, we just won’t know until we get one of these things on our wrist.'”

Some things will be possible to track — how many times people go back to the smartphone app because of something they saw on the watch, for example. But one of the core experiences — the notification — will happen in a kind of data vacuum for publishers. Since the most common technical engagements may be a user either acting on the notification to open a story on their smartphone, saving to read later, or even opting out of notifications altogether, there’s a significant range of responses to a notification that are not captured by a technical, trackable action.

How do you judge the success of a user glancing at a notification — an action that might result in no trackable engagement at all? “For notifications, we don’t have that behavioral data that we do have with a click,” Noah Chestnut said. “If your job is to increase traffic from Facebook, you can get really good at optimizing that. But so much with the notifications on the watch is actually internal — or it’s a conversation in person — and we don’t get that data.

Chestnut sees the challenge as having to rely on qualitative measures, to “ask our users for that data”: “Initially we’re going to use surveys and user panels, and hopefully focus groups and user testing, but it’s kind of like we’re thinking of secondary measures.”

Alex Walters of the Financial Times says they too are planning to use qualitative data to make assessments of a product’s success:

We frequently take test groups of our users and we put new prototypes in front of them so we can establish things like whether articles at full length on a wearable-device screen size work for them. And that really is what dictates how far we go with things.

With a small but growing audience on wearable platforms, news publishers may focus on building loyalty rather than outright visitor growth. At USA Today, Julian Richards is planning on using data to validate their recently released Android Wear extension by looking at retention rather than sheer audience size, saying the organization will be “looking at visit frequency and Wear user lifespan versus baseline audience churn.”

The other commonly cited concern in interviews was that smartwatch operating systems could start to control access to notifications in a more meaningful way, disabling publishers from sending certain types of alert or alerts over a certain frequency threshold.

With most publishers anticipating that notifications will be the primary method of readers encountering their content on a smartwatch — as opposed to a user opting purposefully to open their app — this dependence constitutes a significant issue. Moreover, the diminutive screen and lack of a browsing experience makes routing around OS control, in the manner of the Financial Times’ 2011 move to web apps over iOS apps, practically impossible.

Robin Pembrooke of the BBC sees the role of the operating system in shaping publishers’ products as key:

A critical part of the ecosystem is going to be the extent to which iOS or Android Wear as an underlying platform intelligently begins to refine when and where it surfaces these notifications for people.

What might lead Apple or Google to start rationing access to notifications? Perhaps the fact that the news industry in aggregate is likely to provide a worse user experience to users than news sources would individually. Imagine a significant breaking news story: It would likely trigger multiple notifications from multiple publishers. “The issue for users is that it’s not just around their relationship with one publisher or one service provider,” Pembrooke said. “It’s the fact that these devices aggregate all of these relationships into this cacophony of noise from all manner of different service providers.”

Google Now’s third-party app integration may constitute the most relevant example of publishers allowing Google to intermediate between users and their services in this way. Via Google Now integrations from publishers, initially featuring The Guardian and The Economist, Google now has the potential to surface foreground or background content in Android Wear via Google Now without a publisher initiating that push.

The Times’ Phelps believes Google and Apple could be “constructive counterexamples” in this area, with the collection of personal data a differentiating factor between Google, whose revenue comes primarily from personalized ads, compared to Apple, whose primary business is hardware:

I think Apple has a real problem here. They designed push notifications before anyone really knew how they would be used. If you look at Apple’s guidelines now for how developers are supposed to use push, there are very strict rules that were written probably 4 years ago that say you cannot use push for any sort of marketing purposes. Well, nobody follows that rule, practically. And I’d love to see what those guidelines would look like if they were written today.

There may be room for another category of app innovation from developers who build better ways for notifications to be handled by the OS — in the way that apps like Snowball, a unified messaging app for Android, provides a single product that joins together all of a user’s disparate messaging platforms. At the moment, access to the notification layer is restricted on iOS, though the release of the Apple Watch may prompt a change in that policy:

This could be a critical component if, as many believe, one primary effect of wearable technology will be to accelerate the trend of apps that exist as notifications only. “A notification should exist without the app ever having to exist,” Chestnut said.

Whether or not developers get notification layer access on Apple to handle other apps’ notifications, Apple themselves may have to change notification handling to account for the changing nature of push notifications on Apple Watch.

But in the short term, the policing of responsible notification use from news providers could be restricted to users themselves, who after all have notification control at app and OS level already available to them. As Chestnut argues, users may have already reached a turning point: “A lot of people’s habit is to download a new app and when they’re prompted ‘Do you want notifications?’ — they say no now.”

Whatever happens next with access to push alerts, the situation will be exacerbated by the fact that notifications will be the fundamental interaction model for almost all types of service on smartwatches. As Taylor Davidson said to me: “Every site or app that’s based upon ‘the more I get people to interact with us, the better I do’…is going to say: ‘How do I push stuff to a wearable device?'”

Available exclusively as a preinstalled application on Samsung’s Gear S smartwatch, the Financial Times’ fastFT app, released in August 2014, is one of the very few explicitly wearable-native news apps from a mainstream publisher. Alex Walters, who led product development of the app, described its aim as “a strategic opportunity to test out technology.”

The product is integrated with Spritz, a reading technology company that presents text in a fixed space one word at a time, with the intention of allowing users to read text more quickly. Walters describes the product’s operation:

You’re presented with the last fastFT stories that have been published and…information on roughly how long it’ll take from Spritz for you to read the story at the reading speed you have the device set at. When you tap on one of those headlines, the fastFT story then scrolls across the screen with your eye being led to one letter, usually by a red bar, so you can speed-read the article at the chosen number of words per minute you have the app set at.

For a subscription publisher with an upmarket readership, a luxury technology product tie-in was intended to reach a lucrative and appropriate audience:

We wanted to create an app that allows people to get through fastFT content as quickly as possible because the news that we’re breaking is market moving, so the faster we can get that delivered to our users to enable them to absorb it, the better for them.

Because the product was envisaged as an experiment, it doesn’t yet feature notifications. Alex sums up the challenges for publishers as twofold: first, figuring out which content can be repurposed appropriately for wearable platforms, and second, quantifying the value of the opportunity before starting development:

Because of the limited screen real estate that you’ve got, the main challenge is working out what’s the most important information that we can put on a screen of that size to our users, what will they find most useful to have on that device, and how can we render that content in the most elegant and rich way possible without making it feel cluttered.

The other great challenge is establishing the critical mass of a device or a platform or any kind of mechanism for distributing journalism. We would love to make apps and content provided for all kinds of different weird and wonderful devices, but it’s just not realistic to serve every corner of the market…so we have to establish where our users are.

While even optimistic hardware sales forecasts are fairly muted about the immediate revolutionary potential of wearables, many analysts say they believe the category will attract mainstream interest in coming years. I found that opinion matched, for the most part, within the publishing community. For most organizations, the appetite to embrace wearable technology is more driven by curiosity and branding than by any commercial imperative. The real growth area “still feels like it’s mobile,” says the BBC’s Pembrooke:

At the moment, what this turns into is an arms race for the big publishers to make sure you’ve got your app installed with as many of your loyal users as possible, and I strongly suspect that it is the app on the mobile phone that’ll remain the personalization hub of how you manage your preferences across these devices.

Publishers I interviewed had a mixture of enthusiasm and skepticism for wearable products’ eventual adoption. “Whenever you introduce a new device into people’s lives, the first thing that people do is say, ‘Why would I ever need that? It’ll be a total failure,'” Phelps says. “Cellphones were once ‘for emergencies only’ and definitely not for going on the Internet or reading, and I’m hearing all the same skepticism about the watch…Whenever Apple enters a new device category, people are skeptical and the rollout is a little bumpy — and then it sells like gangbusters. In a couple of years, people will think, ‘I can’t believe we ever didn’t have digital Internet-connected watches on our wrists.'”

Nonetheless, there’s also recognition that Apple’s embrace of a category alone doesn’t guarantee consumer demand. “All sorts of new platforms, devices, and mediums will come in and out of fashion, seem hot but in reality aren’t,” says the Post’s Marburger. “We are paying attention to that, but our job is not to make our readers think that a watch that reads you headlines is the future.”

Matt Galligan at Circa is convinced of the transformative effect Apple can have on the category:

[The Apple Watch] is going to do for wearables what the iPhone did for smartphones and what the iPad did for tablets. We have had these things before, but it won’t be until this moment…that we’ll really see the potential of the space. I think that far too many people are comparing the Apple Watch to any of its predecessors, and that’s no different to someone comparing an iPhone to a BlackBerry and complaining why there’s no physical keyboard. This is going to open up minds, and it’s going to dramatically change a lot of things. There’s a lot left to figure out in the market. We’re not going to understand the full implications for two or three years. But I believe that this thing is going to be huge.

The opportunity for building significant revenue and audience for publishers in wearables in the near term is slight, even if the Apple Watch realizes the potential mobile industry analysts see in it. The advantage to those in the news industry who capitalize on the novelty of the smartwatch platform in its early stages are chiefly focused on the halo effect of being perceived as having ‘cutting edge’ products. There may well also be a small number of commercial native advertising partnerships that could deliver direct revenue as a result.

Smartwatch adoption will be small at first — certainly when compared to the enormous growth in smartphones. But early Apple Watch adopters are likely to be particularly desirable for media companies — young, tech savvy, and with significant disposable income, often combined with an interest in fitness. Publishers that already targeting those wealthier audiences may have an edge.

From a technology perspective, the key shift will be for publishers to consider their iPhone and Android products as deploying onto multiple platforms, with an experience that is linked technically and experientially for users. Phone and watch will be more tightly linked than phone and laptop have been, and much of the user experience will be defined by movement in between devices.

Rather than just moving existing content to a new platform, the key challenge for wearable product creators will be to build and select content on the basis of its relevance to a user, to deliver it in a more personal tone, and to create it so that it can be consumed at a glance. There’s a divide in how users may react to notifications, the defining interaction model of the watch. Some publishers see a content experience that extends from smartwatch to smartphone; others focus on a wearable notification layer than exists without involving an accompanying mobile journey. Particularly in the latter case, the suitability of the content, and its potential to be shared directly from a watch interface are key to developing an effective user experience.

Will the watch drive more attention to our phones or save us from them? Will regularly looking at your wrist be considered more or less rude than pulling out your phone? How new social norms develop around smartwatches will be key to its long-term adoption. (It’s a hurdle Google Glass couldn’t get past.)

While smartphones are used more in the home than when news readers are really on the go, the smartwatch’s low friction user experience may represent the chance to reach people when they are between locations — as well as in traditional digital consumption locations like the home and workplace.

Useful user analytics will be hard or impossible to come by, at least in early versions of these devices. That will make it hard to judge what’s successful or not working about what publishers offer. Qualitative reporting — user panels, focus groups, user testing — will be a necessity for publishers to build a rich picture of users’ wearable experiences.

It will take years for smartwatch adoption to reach significant scale — if it ever does. Apple’s big bet on the device is heartening to those who want to see them succeed. But unlike the iPhone — which promised to reduce your device count by combining your iPod with your cell phone — the Apple Watch proposes the utility of adding an extra device to user’s device profile. Given Apple Watch’s pricing and requirement for a recent accompanying iPhone — and the fact that many consumers are yet to be won over to the smartwatch category’s utility — it could be that Apple Watch, Android Wear, Pebble and others all struggle to find a mainstream foothold.

Jack Riley is head of audience development for The Huffington Post UK and completed this work as a 2015 Visiting Nieman Fellow.