Philadelphia has one of the country’s most vibrant Chinatowns, and as new Chinese restaurants and Chinese-owned businesses open, many have turned to the city’s Latino community for new employees.

The influx of Latinos — many of them recent immigrants — to the city highlights Philadelphia’s changing demographics. That’s a key story for the city’s news outlets to cover, but one that can be difficult for traditional English-language news organizations to report.

“My employer doesn’t speak much English, and neither do I,” restaurant worker Jose Lemos told Ana Gamboa, a reporter with Al Día, a Spanish-language publication in Philadelphia.

Last spring, Al Día partnered with the Chinese-language newspaper Metro Chinese to report on Chinese businesses hiring Latino employees. The story was translated into Spanish and English on Al Día’s website and into Chinese on Metro Chinese’s site.

The coverage is part of a larger effort by Al Día to reach readers outside of Philadelphia’s Spanish-speaking Latino community. In July 2014, the paper launched a responsive English-language version of its website and began publishing original stories in English and translating stories between English and Spanish.

“We have a new generation preferring to read in English, but not necessarily liking what they see in English and in the rest of the media,” Hernán Guaracao, Al Día’s CEO and founder, told me when I visited Al Día’s offices in Philadelphia’s Center City neighborhood last fall.

“They may have switched their language preference, but there’s still desperation to have their stories told in the manner they feel that is representative of themselves,” he said.

Al Día started out as a neighborhood paper in north Philadelphia, publishing its first issue in January 1993. (The Macintosh SE computer used to put out its first issue is still in its office’s conference room.)

Until its recent redesign, the paper only published the occasional story in English — in fact, its use of an English headline on the cover of a 2006 issue was reportedly one of the reasons it lost a defamation case and had to pay out a $210,000 settlement.

In 2014, 13 percent of Philadelphia’s population was Hispanic or Latino, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, up from 11.6 percent in 2010. Philadelphia also boasts one of the fastest growing millennial populations in the United States: From 2010 to 2014, the number of 20- to 34-year-olds living in the city climbed by 33,000.

Al Día is far from the only outlet trying to reach young Latino audiences. That’s the same demographic that ABC and Univision wanted to reach when they launched Fusion in 2013. Other news organizations, such as The New York Times, have taken stabs at translating their stories to reach new and diverse readers.Sixty-two percent of adult American Hispanics are bilingual or primarily speak English, according to a 2013 Pew Research Center survey. By 2020, 34 percent of Hispanics will speak only English at home, an increase from 26 percent in 2013, according to projections by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Al Día hopes to take advantage of all of these of these trends. About 80 percent of sessions on the site are on the English version. The paper averaged 92,000 unique visitors per month in 2015, said Gabriela Guaracao, Al Día’s director of strategy. (She couldn’t give me data from before the paper redesigned its website because “the outdated platform produced data that was inaccurate.”)

“The numbers indicate that Latinos are dual-language citizens,” said Sabrina Vourvoulias, Al Día’s managing editor. “The younger they are, the more likely they are to want to read certain aspects of what they look for online in English. Very often, other aspects in Spanish. It became very clear, just from a numbers standpoint, that it’s something that needed to be upped.”

Most of the stories on Al Día’s most-read list are English-language stories that tend to do well on social media, such as “Philly’s new mayor dressed up as Buddy the Elf” and “Estas son las ciudades de EE.UU. donde más alcohol se consume” (“These are the drunkest cities in the United States”).

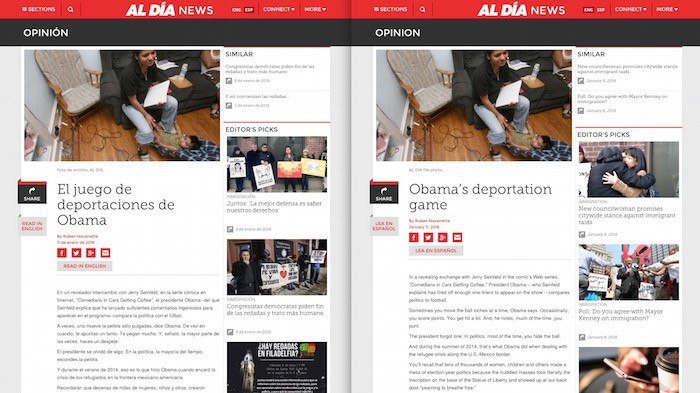

Each Al Día story page includes a button that says, “Read in English” or “Lea en Espanol,” which allows readers to flip seamlessly between the languages.

About 70 percent of Al Día’s stories are translated from one language to the other, Vourvoulias said. About half of Al Día’s six staff writers prefer to write in English and half prefer to write in Spanish.

Editors translate each piece, which means the process can take some time. Al Día often publish a story in one language first, then spends more time on the translation, ensuring that it captures the nuances of the original story.

“It’s slow because it’s a human translation process,” Vourvoulias said. “But there’s no way to replicate the voice of the person who is writing [using machine translation].”

Still, Al Día seems to recognize — and crave — the additional attention that comes with publishing in English.

2015 was a big year for the paper. There was a Philadelphia mayoral election, Pope Francis visited the city, and Donald Trump brought immigration issues to the forefront. Al Día saw its reporting cited in other outlets in the city.

“We’re doing a lot of work designing, reporting, and writing, and yet it didn’t reach many more people than we’ve been reaching for all these years,” Guaracao said. “We published in English and now people are reacting to it.”

Al Día has also turned to events to reach beyond its core Latino audience (and generate a little revenue). Last year, it hosted a forum for Philadelphia’s mayoral candidates and partnered with journalists from a number of different outlets — such as the Daily News and Billy Penn — to ask questions.It has also held events focused on less newsy topics: A talk and tasting last year featured a chef from a popular Mexican restaurant; an upcoming event will feature a whiskey tasting, film screening, and discussion.

Though Al Día continues to expand its offerings, the paper’s staffers say the Latino-American experience remains at the heart of everything they are trying to do.

“My whole thing is that we code-switch,” Vourvoulias said. “Everyone does it to some extent. You code-switch from one language to the other. I would hope that that is also what our website does: It code-switches from Spanish to English at will. You go from one to the other, but you hear the same voice in both.”