Hours before the first polls closed on Super Tuesday, my phone buzzed. I had a new text message.

“Ahhh I’m so excited Joseph! Today is Super Tuesday, the most important day of the election thus far. 12 states are holding their primaries today and I’ll be following the action. Text LIVE to follow it with me, or AFTER if you just want to hear what happens after it’s all over.”

“Ahhh I’m so excited Joseph! Today is Super Tuesday, the most important day of the election thus far. 12 states are holding their primaries today and I’ll be following the action. Text LIVE to follow it with me, or AFTER if you just want to hear what happens after it’s all over.”

The text came from Purple, an SMS-based service that is covering the presidential election through text messages. Purple lets users opt into live coverage of events such as primary results or debates while also offering analysis and background on the race.

I chose to follow along live, and as the night progressed, Purple sent out updates as Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton claimed resounding victories. The texts included quotes from each candidates’ remarks to their supporters, delegate math, and links to additional coverage at outlets such as FiveThirtyEight, and Politico.

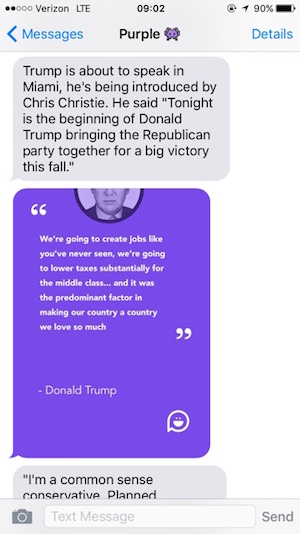

“Trump is about to speak in Miami, he’s being introduced by Chris Christie. He said ‘Tonight is the beginning of Donald Trump bringing the Republican party together for a big victory this fall,'” Purple reported as Trump was about to take the stage to declare victory.

“Trump is about to speak in Miami, he’s being introduced by Chris Christie. He said ‘Tonight is the beginning of Donald Trump bringing the Republican party together for a big victory this fall,'” Purple reported as Trump was about to take the stage to declare victory.

After Hillary Clinton narrowly won the Massachusetts primary, Purple texted: “Aaaaaand Massachusetts goes to Hillary, big blow for Bernie.”

Purple aims to inform its users in a friendly way without overwhelming them with a seemingly endless stream of content. Last Thursday night, during the most recent Republican debate, I was at a dinner celebrating a friend’s birthday, and Purple’s text messages were an unobtrusive way to follow along without staying constantly glued to my phone. (Though Purple didn’t cover the most talked about part of the debate: When Trump, Marco Rubio, and Ted Cruz took turns insulting one another in rapid succession.)

Purple CEO and co-founder Rebecca Harris, who graduated last year from CUNY’s entrepreneurial journalism program and describers herself as a “huge politics nerd,” said the company decided to focus initially on text messages because it’s easier than getting people to download and use another new app.

“It’s by far the most ingrained common behavior that we already use with our phones,” Harris told me. “Messaging platforms have overtaken social media. It’s where user engagement is.”

Purple plans to expand to other messaging platforms, including WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and Slack.

It’s also expanding its coverage to include sports, starting with the NCAA basketball tournament later this month. Purple is looking into topics like business and music, Harris said, explaining that the ultimate goal is to let users customize their feeds based on their interests.

Purple initially launched as a political website and email newsletter. Last November, though, she and co-founder David Heimann, decided to relaunch it as a messaging service with a test group of 50 users. More than 800 people have now signed up for the service, and the growth has all been organic. “We haven’t spent a dime on marketing,” Harris said.

So far, Harris and Heimann have funded Purple with support from their families and friends. They said some outside investors have expressed interest.

Harris said Purple is looking at a number of ways to monetize the service, including adding advertising or paid subscriptions of some sort, but “revenue is a bit of a ways off for us.”

“Our focus right now is on the product and user growth,” she said. “Monetization is going to be contingent on the volume of users.”

As the number of people using messaging apps has increased — half of smartphone users between the ages of 18 and 29 use a messaging app such as WhatsApp or iMessage, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center survey — news organizations have turned to them to reach younger audiences.

A handful of examples: The Guardian covered a GOP debate on WhatsApp in December, The Economist has been publishing charts directly to Line, and The New York Times has been sending election updates to Slack. The WNYC podcast “Note to Self” also recently sent 300,000 texts to 15,000 people as part of an experiment to measure information overload.WNYC used Twilio, a platform that lets developers program text messages and phone calls to power its experiment.

Purple is also built on Twilio, and Harris writes all the messages that Purple sends. She said her aim is to make them feel conversational and fun, while also remaining accurate and non-partisan.

“What’s going to make it successful is your ability to have a voice, to talk to people like you would talk to anyone else,” she said.

About 85 percent of the messages are automated. Many of the messages Purple sends have keywords written in capital letters, and if users respond with those words they’ll get a response with more detailed information.

About 85 percent of the messages are automated. Many of the messages Purple sends have keywords written in capital letters, and if users respond with those words they’ll get a response with more detailed information.

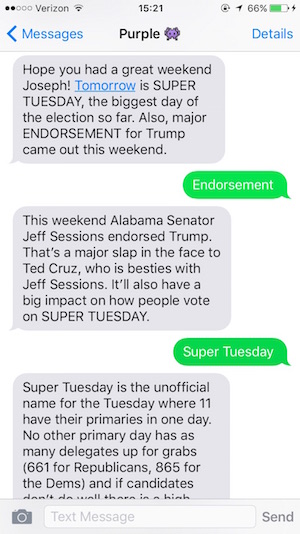

On Monday afternoon, for example, Purple texted me a reminder that Super Tuesday was coming up.

“Hope you had a great weekend Joseph! Tomorrow is SUPER TUESDAY, the biggest day of the election so far. Also, major ENDORSEMENT for Trump came out this weekend.”

By replying with “endorsement,” I got details about Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions’ support of Trump and how it was “a major slap in the face to Ted Cruz, who is besties” with Sessions. By texting “Super Tuesday,” I got details on how many delegates will be awarded. Additional texts let me drill down to specific state-by-state previews.

Users can also use the keywords to choose how they want to receive the text alerts. Prior to the debates, Purple let users pick whether they want live updates through the course of the night or just a summary sent to them when the event is over. Similarly, because the results in the Nevada Republican caucuses didn’t come in until after midnight Eastern time, Purple offered users the option to wait to get results until the morning.

Users can also use the keywords to choose how they want to receive the text alerts. Prior to the debates, Purple let users pick whether they want live updates through the course of the night or just a summary sent to them when the event is over. Similarly, because the results in the Nevada Republican caucuses didn’t come in until after midnight Eastern time, Purple offered users the option to wait to get results until the morning.

Beyond the automated responses, Harris will also respond to users’ specific questions, which she estimated accounted for about 15 percent of the replies.

Regardless of how users interact with Purple, the goal, Harris said, is to make it seem more personal than a typical news source.

“They think of us as their politics nerd friends,” Harris said.