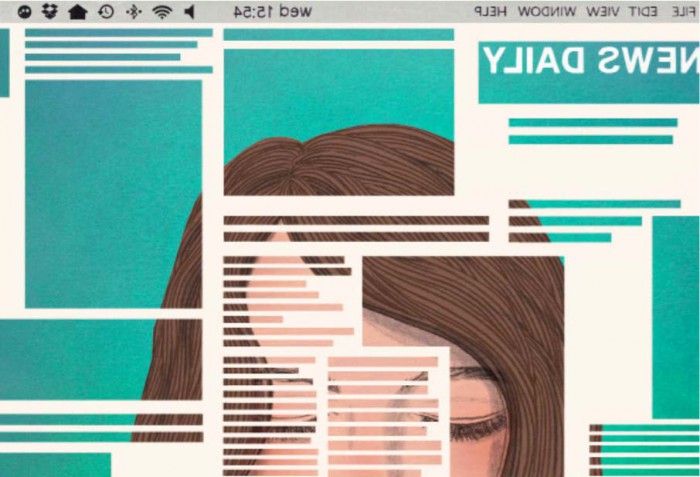

Editor’s note: There are lots of new stories to read in the newest issue of our sister publication Nieman Reports. In this piece, Michael Fitzgerald writes about how newsrooms can (and should) design their websites with accessibility in mind.

Elizabeth Campbell doesn’t see the web; she hears it.

Campbell is blind and uses a program called JAWS that reads aloud the text on a web page. The problem is, JAWS reads all the text. “I’ll be reading along and JAWS will start reading an ad right in the middle of a story,” she says. “A sighted person would see the same thing, but you guys can skim over it and skip the ad, where we have to figure out how far to go down so we can get back to the story.” The more ads, the more likely a site is to make JAWS crash.

Cluttered designs stuffed with ads and other graphics give JAWS problems, especially if a site isn’t programmed to make the text easy to interpret. So Campbell often tries a different browser. She might also use Apple’s VoiceOver software on her iPhone, pulling up the article on the web or even switching over to the publication’s mobile app. Facebook is helpful because it makes text more accessible than many news sites and apps. As a last resort, Campbell, a general assignment reporter at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, uses NFB-Newsline Online, a service of the National Federation of the Blind that reads news content aloud.

If that sounds like a cumbersome way to read an article, it’s also progress. “Even when I have challenges with access,” Campbell is quick to say, “it’s just amazing what we can do and what we can access as opposed to 30 years ago.”

According to Census Bureau surveys, nearly one in five Americans reported having a disability in 2010. Many are motor or cognitive disabilities, including dementia and depression. But more than eight million Americans are visually impaired, and more than 7.5 million have hearing issues. For people with disabilities, accessing the web can devolve into the online bunny hop Elizabeth Campbell sometimes experiences.

While standards exist for creating accessible content online for those with disabilities, they are entirely voluntary for news sites. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a law requiring people with disabilities to be afforded equal access in public spaces, mandates things like wheelchair ramps, Braille signs, and handicapped parking. No such broad-based legal protections exist for the Internet. But for news organizations interested in reaching the widest possible audiences, and for journalists who see it as their mission to represent readers’ interests, ensuring equal access to online content is essential.

Campbell wants to see the government extend the ADA online, treating the Internet like a public space where companies must design sites the way they design buildings — to ensure access for people with disabilities. That means incorporating things like descriptive tags for photos, videos, and interactive graphics so blind people can know the context of a photo caption; adding closed-captioning to online videos so deaf people can follow stories, and creating basic page designs for the web and mobile apps that make it simple for people with various disabilities to skip over images.