The independently owned TV Rain (in Russian: Dozhd, meaning rain) was founded in 2010 by businessman Alexander Vinokurov and his wife Natalia Sindeyeva and hit a wall in February 2014, when major cable providers in Russia began to drop the channel after the website ran a poll on the 70th anniversary of the Siege of Leningrad asking whether the Soviets should have surrendered then. (Hundreds of thousands died in the siege.) Public outrage was immense, and TV Rain removed the poll, with an apology.

At least, that was the reason the providers gave. But given TV Rain’s history of coverage of sensitive political issues and aggressive reporting of prominent figures’ activities, and the stifling media environment created by the Russian government, many connected the dots between an unhappy Kremlin and attempts to drive TV Rain out of business indirectly by squeezing providers. TV Rain lost 90 percent of its viewership, and advertisers fled.

TV Rain actually instituted its paywall in September 2013, intending it to be just an additional a revenue stream. At the time, advertising was its main source of income.“When we introduced a paywall almost three years ago, we understood that our business model was more about advertisements, and we also understood that was not so stable,” Lena Kiryushina, digital director for TV Rain, said. “Then we decided we needed to introduce a paywall — but we never thought that would be our future.”

In 2014, it launched a full-fledged subscription campaign, with renewed urgency.

“When we were kicked out of all the major networks in Russia, we probably wouldn’t have made it, we probably wouldn’t exist, wouldn’t be sitting in front of you right now,” Ilya Klishin, editor-in-chief of TV Rain’s website, said. “Really, this was pretty much the only source that could help us go through.”

Все главные новости этого дня — в одной программе:https://t.co/KSP2bIvuGS

— Телеканал Дождь (@tvrain) July 11, 2016

TV Rain now has more than 70,000 paying subscribers who pay for access to its flagship programs, news shows, special long reports, and live broadcasts, which TV Rain will sometimes open up to everyone in special cases, such as terrorist attacks. Paywalled videos certainly don’t handle Putin’s reputation with kid gloves: this investigation into his personal chef, for instance, or a piece on “Kremlin chroniclers,” journalists who traveled with Putin. It’s reported from Donbass in Eastern Ukraine. But Klishin emphasized that he doesn’t want the site to be described as “oppositionist,” he said, because “that’s what we’re called by our critics in the government,” and “we want to give both sides a place to talk” (though admittedly, getting government officials to come on TV Rain programs willingly has gotten harder).

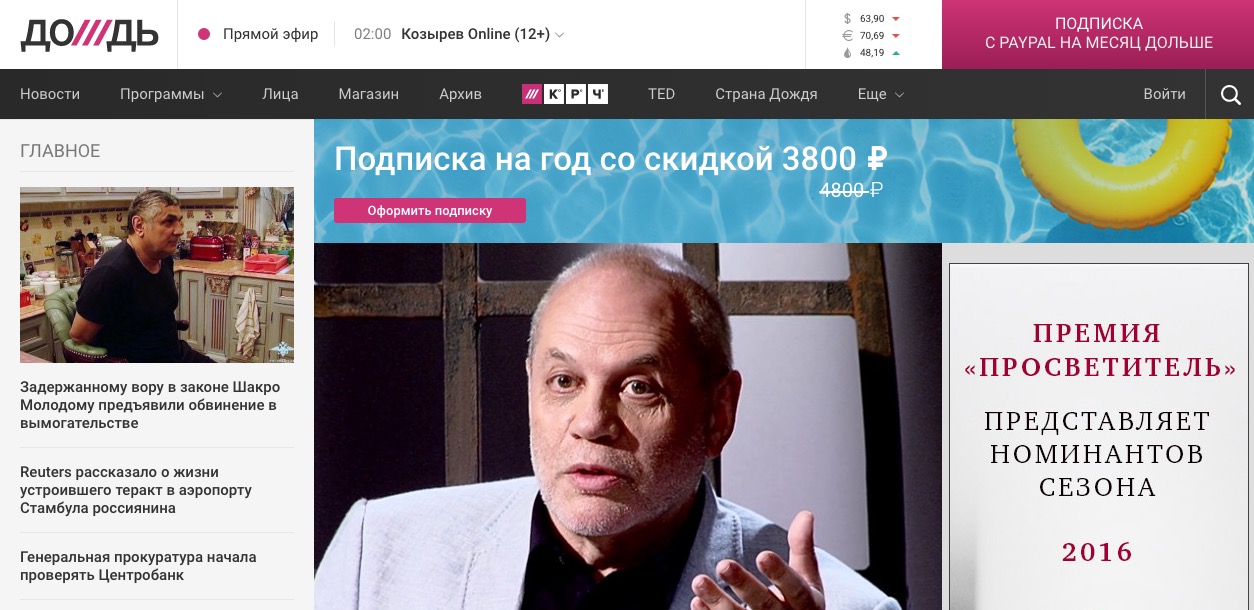

Beyond special coverage, there are other special perks to membership, including a closed Facebook group where subscribers can pose questions and discuss coverage with TV Rain journalists directly. Commenting on all platforms are also open only to subscribers. A year-long subscription costs ₽4,800 rubles (about $73 at the time this story was published), though it’s currently running a summer offer of ₽3,800 rubles for a year. One-month and three-month options are also available.

For a time after the early 2014 crisis, TV Rain was even forced to continue broadcasting from an apartment after it was evicted from its old studios, its dispatches looking very makeshift. But as a TV station, it’s conveniently positioned to produce digital video, at a time when news outlets are frantically hopping on board the social media video train. It’s repackaging longer programs into five-or-so minute video for social, following the formula of places like AJ+ and NowThis.

TV Rain has a staff of under 200, and about 10 to 12 people are dedicated to the website (that number is higher if you count developers; the TV programming requires far more production staff). It had to iron out miscommunication between the TV and digital sides; at one point, someone reporting for a broadcast might call a source, and someone writing a text story for the website would do the same, separately.

“I guess it took us three years to realize we were no longer an ordinary cable TV channel, but a media platform with a live broadcast component, that also is able to have a lot of videos on demand, a lot of articles, which are text,” Klishin said. “Far more people are reading and viewing us online than viewing us through TV screens. Once, when news would happen, we would wait until the evening broadcast. Why were we waiting? At times it felt foolish. Now, as soon as we get any video, any news, it goes first onto our website.”

Putting up the paywall slowed the site’s growth, Klishin said, though the web audience has tripled in the past three years. Its Facebook page has also grown to over a million fans and TV Rain has about two million followers on Twitter.

In a reversal from three years ago, subscriptions now make up 60 percent of TV Rain’s revenue, while around 20 percent comes from advertising, according to Kiryushina and Klishin. Distribution through smaller cable systems make up another 20 percent. The site is averaging four to five million unique visitors per month (fluctuating between 18 and 27 million pageviews per month). A substantial number of text stories and shorter video segments are all outside the paywall, covering both breaking news and “the usual Internet stuff”: In addition to hard news, I browsed with the help of Google translate stories on Leonardo DiCaprio potentially playing Vladimir Putin in an upcoming movie, permanent resident Larry the cat at 10 Downing Street, and of course, a TV Rain journalist demonstrating Pokémon Go in the newsroom.

The political pressure against TV Rain continues. Earlier this month, a pro-Kremlin group made allegations to state prosecutors that TV Rain was violating state media law in its reporting on the Islamic State.

But whether it was more business imperatives or political pressures that pushed TV Rain to implement the subscription model that essentially saved it from extinction, Kiryushina and Klishin said it was difficult for them to say. Its own journalists struggled a little with the change: “We had, at one point before February 2014, 12 million people watching on TV. Our journalists went from that, to making their content primarily for a web audience, which is four, five, six million? It can be hard to switch that mindset,” Kiryushina said.

“It’s interesting, I think, that two years ago, our subscribers understood that they were helping to save our channel, to save freedom of speech,” she added. “Now they understand they aren’t saving us, they’re buying premium content. The message is a little different now.”