Editor’s note: Matthew Yglesias of Vox riled a lot of journalists’ feathers this week with his piece “Against transparency,” which argued making public officials’ emails subject to records requests from journalists (or others) is a bad policy. Here, Michael Morisy, cofounder of the FOIA-driven site MuckRock, responds.

As much as journalists hate to admit it, FOIA is not really for them. FOIA is for the public, ensuring that voters have meaningful oversight of work done in their name. Giving a blanket exemption to emails, Slack chats, and other “conversational” communication tools would disastrously break that oversight — and undermine the ongoing American experiment of an informed democracy.

Matthew Yglesias, writing for Vox, argues that leaving emails and other electronic messages subject to FOIA hurts effective governance:

The relevant laws were written decades ago, in an era when the dichotomy between written words (memos and letters) and spoken words (phone calls and meetings) was much starker than it is today. And because they are written down, emails are treated like formal memos rather than like informal conversations…Treating email as public by default rather than private like phone calls does not serve the public interest. Rather than public servants communicating with the best tool available for communication purposes, they’re communicating with an arbitrary legal distinction in mind.

Unfortunately, Yglesias has a lot of misconceptions about how FOIA works, as folks who live and breathe FOIA widely noted.

.@voxdotcom got this dead wrong. Among other things,not 1 mention of existing #FOIA exemptions that protect privacy and deliberative procoss— Lauren Harper (@LaurenLeHarper) September 6, 2016

Yes, mention FOIA to a government employee, and there’s a better-than-even chance that they’ll roll their eyes. It’s a pain, but it’s not carte blanche to access everything an official sends.

But beyond these and a number of other inaccuracies, Yglesias is wrong about why emails should be subject to FOIA for two critical reasons:

The first aspect is pretty straight forward: When reporters and the public can request emails, it makes it easier for meaningful accountability to happen. Yglesias writes:

Under current law, if Bill Clinton wants to ask his wife to do something wildly inappropriate as a favor to one of his Clinton Foundation donors, all he has to do is ask her in person…Information is disclosed on request to the requesting parties — which has turned it into a very slow, highly adversarial process that’s primarily useful to people with an ax to grind.

It’s true that there are an almost infinite number of workarounds to public records law that officials can use. But it’s also true that time and again, requests for officials emails have turned up important information that led to reforms.

Just a few of these stories based on FOIA’d emails:

This is just a tiny sample of all the accountability reporting that happens specifically because emails are subject to FOIA. The results are nonpartisan.

If you read any accountability journalism, it’s amazing how often emails received through public records requests and the Freedom of Information Act provide a pivotal role. If anything, stories based on public records stories tend to be the antidote to the “hot take” culture that Yglesias worries is corrupting good government.

Plus, even government phone calls are often recorded and provide important accountability. One great example, via the Associated Press’ Ted Bridis: How a No Fly Zone over Ferguson — originally stated as a public safety measure — was actually created to keep the media away.

Making emails and other modern communication channels exempt from FOIA means that most of these stories would be impossible, or at least much weaker. Instead, reporters would have to rely on citing “according to sources,” which leaves their reporting vulnerable to he-said-she-said back and forth that inevitably dulls its impact.

The other half of Yglesias’ argument, that too much oversight impairs government work, also misses the mark. He’s absolutely right that government employees need the ability to brainstorm and speak candidly. This is what the B(5) exemption, phone calls, and in-person meetings let them do. But it’s equally important that government officials get used to working in public — aware that part of their job is being able and ready to share, explain, and occasionally defend their work.

The more routine they make that practice, and the more deeply ingrained it is in their culture, the harder it is for anyone to turn it into a “gotcha.”

As one case study, take a look at how Jeb Bush handled requests for emails during his tenure as governor of Florida. It was not well handled: The emails included social security numbers and other private information, which later had to be pulled offline, redacted, and then re-released.

But dumping email early and often generally worked out for him: Dubbed “the email governor,” he addressed potential scandals that surfaced in his emails and moved on, as did voters. For all its faults, his campaign was never dogged by even his more controversial missives.

And that culture of disclosure is deeply ingrained in Florida, a state known for its expansive public records laws. I spoke with an official there several years ago who said that most organization charts in the state put the people up top:

Perhaps its a small, symbolic move, but it helps serves as a reminder: When you work in government, the people are your boss. And the boss has a right to see your work.

Yglesias:

Outside of the specific context of American politics, nobody thinks these messages should be treated socially or legally as the equivalent of official memos rather than phone calls or oral conversations

Which is odd, since this routinely happens in private businesses when companies do internal reviews to address issues ranging from sexual harassment to fraud. The Securities and Exchange Commission, in fact, has incredibly strict guidance regarding how internal messages — regardless of medium — need to be retained for all public companies.

Over the course of helping MuckRock’s users file almost 25,000 requests, almost all of the officials I’ve had the pleasure to work with agree on the issue of openness, but agencies’ culture of transparency varies widely — not because some are malicious or take their job less seriously, but because when you’re not used to oversight, it can be extremely uncomfortable. But when you sign up for working in government, it’s essential that it comes with the job.

Some agencies act as if they were the custodians of government records on behalf of the public — these agencies invariably seem to work with requesters on ways to make more public, and generally have stronger relations with the press and more trust with voters. Other agencies treat requests more grudgingly, and it has a ripple effect up. If you fight over whether trivial information is released, it’s hard to trust you with more important information.

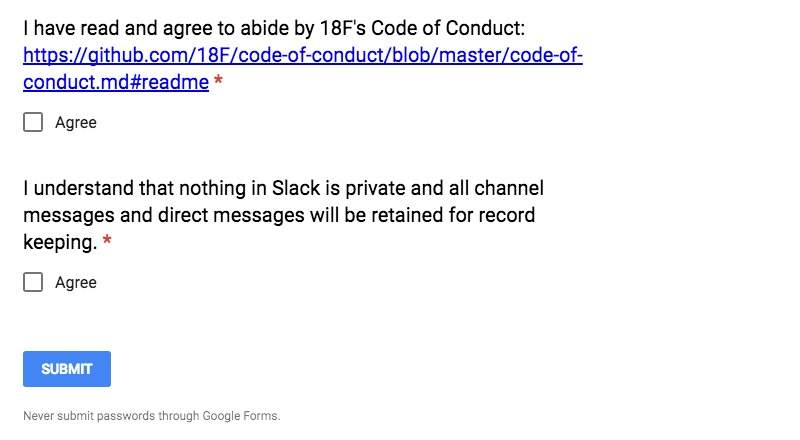

18F, the federal government’s in-house digital services agency, has done a great job of working to embrace openness as a core value, doing much of its programming work in public on GitHub and even working to open up much of its Slack conversations to the public.

That strategy has seemed to work: 18F has achieved a lot, and what scandals have emerged have been taken in stride, with the agency preferring open and honest communication around the challenges as they move to update the technological engines of governance for the digital age.

Another of my favorite examples is the Colorado city of Fort Collins, which has proactively released every city council email not specially marked private for the past two years.

Anyone can log in and search email at will, and it’s worked well enough that the council has kept up the practice (try it yourself here; login councilemail@fcgov.com, password City-80521).

What typically hurts officials is when they fight requests, rather than embracing them as an opportunity to share their work with constituents.