What should the experience of a magazine be when it’s moved online?

As the subscription-based Harvard Business Review drops from 10 print issues a year to six in 2017, it’s looking for those new formats through six new online series, each of which will be a multi-day, multimedia package organized around a single concept. The metaphor of the print magazine is useful for understanding the editorial structure of these series, which HBR is calling “The Big Idea.”“In each magazine issue, we have a spotlight where we collect a bunch of articles about a topic — an idea that’s big enough that we want to devote more than one article to it,” Scott Berinato, the senior editor at HBR who helped lead development of the Big Idea project, said. “The Big Idea is the digital manifestation of that — it’s a single idea we want to devote more storytelling resources and web approaches to, to get more people to convene around it.”

“The print magazine has its own long, rigorously researched articles. This is an equally rigorously researched longform idea, presented digitally first. That’s a serious departure for us,” Amy Bernstein, editor of Harvard Business Review, added.

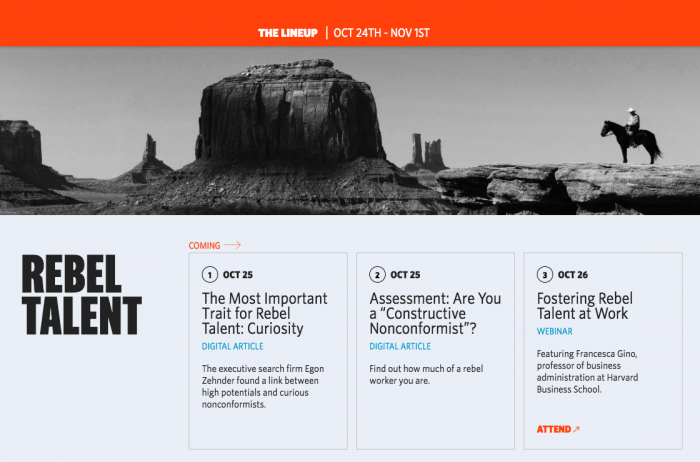

The first “Big Idea” series is a week-long effort centered around work by Harvard Business School professor Francesca Gino about the benefits of nonconformity in the workplace. It will culminate in a reception and roundtable discussion in San Francisco featuring Gino and Pixar cofounder Ed Catmull. HBR is dropping one piece of content each day — a long article packed with research, case studies, and recommendations on Monday; a quiz for users to determine whether they are “constructive noncomformists” on Tuesday; a webinar with Gino on Wednesday — and sold out its capstone event within a few days.

The launch of each Big Idea will be staggered with the publication of print issues, and the content of the digital series and the print issues will not overlap. The next digital series, launching in late January, features Wharton professor Adam Grant’s work on the “dark side of generosity.” Subsequent Big Ideas will be structured similarly — with lavish digital presentation and multimedia elements released over the course of a week or two — but the exact format of the individual elements may vary.

“Sometimes a piece is so good, we really wish we could have it for print. But we’re trying to get away from ‘it should’ve been in print, but it couldn’t be because of the lack of physical space,'” Josh Macht, publisher of the Harvard Business Review Group, said. “We’re trying to get to the point where this idea could only be in the Big Idea. That’s going to take some time to figure out.”Part of picking the “right” idea means looping in the right authors: People who can help brainstorm ways to represent their research beyond article form, can be compelling live, and can help promote the pieces. HBR is also conscientious about “making this worth the author’s time” and wants authors to feel they’re “getting value out of time spent,” Sarah McConville, HBR Group’s VP of marketing and publisher of Harvard Business Review Press, said.

Gino’s Rebel Talent series is in front of HBR’s digital paywall (which lets logged-out visitors read four free articles a month; logged-in visitors can read eight) to drive awareness for the series, and HBR is still considering how best to integrate it with a paywall in the future. There’s no advertising in Rebel Talent online, but “we’ll move there,” according to Macht. “Eventually, sponsorship will be tied into all of this.”

The project is an “experiment” that aims to attract a new generation of HBR readers (who might become paying subscribers). It’s one step in a larger HBR rethink that’s taken place over the past couple of years, which also includes a redesigned print magazine, new products like the Visual Library for charts and graphs, and a reworked pricing structure. HBR’s paid circulation isn’t declining (it was 278,241 for the period ending June 30, 2016, according to Alliance for Audited Media), and the newsstand price of each issue will increase from $16.95 to $18.95, starting with the January/February 2017 issue.

An in-house team built a custom, mobile-friendly template for the series; it includes a variety of bells and whistles, including email updates dedicated to a single project and design elements like parallax scroll. An “add-to-calendar” feature is rolling out soon.

“We’re trying to build daily habits with digital content,” Katherine Bell, editor of HBR.org, said. “A [print] magazine encourages occasional, really deep engagement with big new ideas. When we went down in frequency, we didn’t want to lose that. It’s a way to keep that rhythm and get the space to experiment.”

Editors will scrutinize reader engagement, from newsletter signups to social shares to less tangible metrics around whether HBR ideas are making an impact in the workplace. More than three visits a month to HBR’s site is a strong indicator that a reader will subscribe or renew, so building an online experience that encourages repeat visits is critical.

“I’m curious to know if we’re attracting a different kind of reader with this treatment,” McConville said. “Will we be able to open up HBR to someone who discovered it because a friend referred them to it, or because they saw something on social? This showcases a lot of the things we do digitally, that you may not be aware we do.”

As a subscription product, HBR has weathered digital upheaval relatively well (its model is 25 percent advertising, 75 percent subscriptions and paid content). But print advertising was flat between 2015 and 2016.

“Our print is fine, but we’re also not idiots,” Adi Ignatius, editor-in-chief of HBR, said. “We’ve done a lot of research that suggests readers don’t care so much what we do with the print magazine — whether six, eight, or 12 issues a year. The important thing is, are they getting value? And value seems to mean pieces every year that speak to them. We’re just trying to get ahead of how people consume things.”