The Verge launched five years ago today — a lifetime ago in the online news business. The site was designed for the desktop with bold, chunky visuals; the colorful rectangles on the home page were a departure from the timeline-style homepages common then.

What lessons can news sites learn from the bold launch of The Verge? Here are three http://t.co/4Hg7x96z

— Nieman Lab (@NiemanLab) November 1, 2011

Today, to mark the anniversary, the site is launching a redesign that epitomizes the changes that have swept through the media business since 2011. The website is getting a refresh, and The Verge is also debuting a matching set of graphics and animations that will accompany its videos and designs on platforms like Facebook and YouTube.

I spoke with Verge editor-in-chief Nilay Patel and engagement editor Helen Havlak (with a Vox Media spokeswoman listening in) about the thinking behind the redesign and the lessons they’ve learned over The Verge’s history. What follows is a condensed and lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

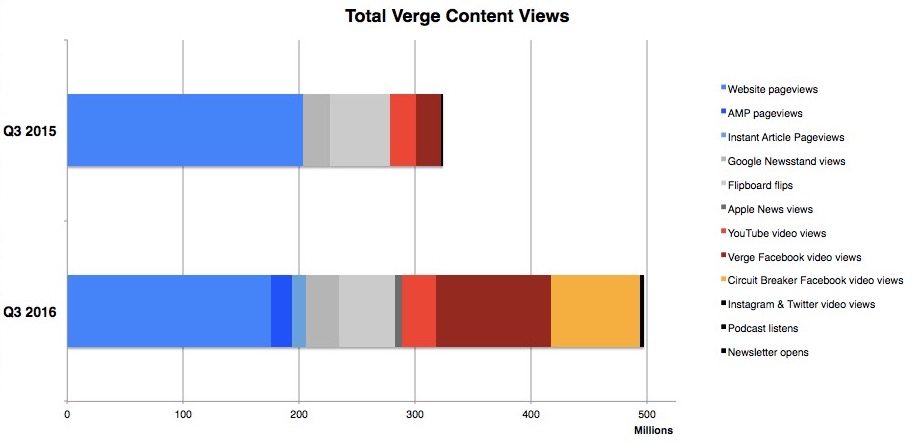

But as we look at the landscape now, that site, the 2011 site, was designed around a singular desktop experience. That’s no longer how our audience finds us; our audience finds us across platforms. We wanted to keep that big, striking desktop presentation, and make it cleaner and more powerful for the users who are more loyal to us on that platform, but we wanted to build a design system that allows us to extend onto other platforms like Instant Articles and Google AMP. We have an enormous and growing video operation that needs to tie into that design system, and we wanted the whole thing to be faster and render better on mobile.

Our entire team is built around finding the biggest stories in tech, the biggest stories in culture, and the collisions between those two things. Our entire team is hyperaware of all the platforms we publish to and how to make stories work best on those. There are few organizations with video as tightly integrated into the editorial team as ours.

Part of the redesign has been a project of redoing the animations of the videos, redoing how lower-thirds look, redoing what the thumbnails are going to look like, redoing how everything ends, and making sure that all the different elements of the desktop redesign are elements that can move and animate within video. That’s critically important for getting things on YouTube, but also for Facebook video and even Instagram Stories.

There’s the very standard thing that works on Facebook: You start with three seconds of something interesting happening, and that’s great, but the next turn that’s going to come in that format is finding new and exciting ways to tell bigger stories, rather than just looking at a thing.

Circuit Breaker, because it’s a shortform gadget blog, gives us freedom to do crazy things. The editor, Paul Miller, and his team are incredibly good at doing fun wacky things with video — whether it’s just “listen to this mechanical keyboard for 60 seconds” or “take this bonkers coat to see how many gadgets we can hide in the pockets.”

We’re having tons of fun with Facebook Live, and the series to watch that Circuit Breaker just launched a couple of weeks ago is Emotional Tech Support where they give Facebook users a telephone number and let them call into a live Facebook show. They don’t solve people’s tech problems, but they hear them out and provide emotional support.

This moment, for us, is about deepening the focus of our execution. I’m really interested in how technology is changing the world; that’s the thesis of The Verge. Talking about how it intersects with the culture, in particular, is the most important thing we can do. If you look at our four sections, science is where all of this stuff begins; it’s where our biggest ideas happen. Elon Musk wants to go to Mars. That is the next generation of science stories. There’s also a whole bunch of material science stories. Batteries are exploding — that’s a chemistry story. There’s a lot that we need to do to connect technology to where it comes from, its basic building blocks, and where it can go. Technology is also affecting health in a real, serious way. The science of our bodies in this case is rapidly being disrupted by the tech industry.

Then there’s our core tech coverage. You can tell that we have a new focus there with Circuit Breaker and gadgets, but then there’s the entire app economy, there’s Casey Newton finding crazy stories about bots in Silicon Valley, we have a huge reviews program. That’s getting deeper and more focused as well.

If you look at our culture coverage, what we’ve really started to do is look at the tools that creators use to make the culture, how the stuff is distributed, and how that stuff impacts what actually gets made. Westworld is straight up a show about robots. So much of culture has started to depend on tech in really serious ways to tell the stories. There’s an entire world of opportunity there for us, in terms of talking about what gets made, how it gets made, how it’s distributed, and why. We’re also really interested in who makes the stuff, because as technology democratizes the tools, the diversity and inclusiveness of the creator class and the audience are getting really, really different, and it’s really important that The Verge values technology inclusively.

I can keep going. The Internet has spawned an entire range of memes and cultural moments, whether it’s what just happened with Vine or whether it’s Black Lives Matter. Those are stories about technology changing the way we talk and interact with each other and our expectations about how our society treats one another.

We have a big transportation section that is really vibrant and has some of our best audience growth. If you think about how all of the things that I just mentioned come together, where they are going to have the most impact on society is on how the hell we move around — whether the cars drive themselves; whether public transit becomes all hyperloops; whether self-driving trucks mean we don’t need to have rest stops or even towns anymore; what we do while the cars drive themselves; how the entire industry producing all this stuff in America gets changed. Literally every piece of science, technology, and culture collides in the future of the transportation industry.

We feel very confident that the bet we made about technology changing culture in 2011 was the right bet. It’s the bet we can make again for the next five years. Doing it right, and doing it at our scale with our depth and with our scope, is so much harder than it looks and we just have to stay committed to it.

The biggest challenge, the hardest one, has been our video strategy: why we make videos, who we make videos for, what kind of stories we want to tell with video, what platforms the videos belong on.

When we started in 2011, it was as if we weren’t aware of YouTube. We published all of our videos to a custom player — from a startup that failed, actually; in the middle of our first year we had to switch to another custom player. Our entire video strategy was about producing little documentaries for our website. We went through 900 revisions of that strategy. It never really worked. It never really clicked. We made some great stuff, the people who made those videos are extraordinarily talented, but it never really hit the way we wanted it to hit.

In the relaunch, “video” in our nav bar is going to take you directly to our YouTube page. We’re walking away from the idea that all our video has to be viewed in an app experience on our desktop website. We know that the primary platform for the kind of people who click on the video link is YouTube. We know that YouTube is the second biggest search engine in the world, and we’re going to lean into that for a lot of the more narrative personality-driven videos we want to do.

We also know that Facebook is a massive, growing platform. We’ve done almost as many Circuit Breaker views off those 500,000 followers as we’ve done on YouTube with 2 million followers. We have to invent different formats for that platform. That is a way more sophisticated, more hard-fought set of strategies around video than “let’s run out in the world, make a bunch of documentaries and put them in a website in a player.” We still have custom players on the platform; the experience on the website is way better. When you click the play button the video opens in-line. It’s been iteratively improved, but I’d say we’ve learned the hard way that to have a sophisticated video strategy means being sophisticated about video platforms.

The way I’m thinking about it right now is that we’ve moved from RSS readers and desktop web to very much having our stuff mediated by a series of icons on homescreens. Our web experience and our AMP experience are going to come at you through mobile search, and if you’re one of our most loyal readers, you’re going to type “The Verge” into mobile Safari. I know we have a big audience on the Twitter icon. I know that there are lots of ways to capture a big audience for text and video on the Facebook icon. I know that lots and lots of people have the YouTube icon on their homepage. Those are the four icons right now, the four icons everyone has on their screen.

Photography is what travels to every platform. It’s usable and reusable everywhere we go, just as much as text is, and in many cases like Instagram it works more effectively than text.

We’re also good at knowing which of these platforms are a flash in a pan. To get an icon onto a homescreen, you have to do something that almost no one can do now. The average number of apps downloaded by the average user is zero. The platform bets for us are related to our core tech coverage about how different companies and different distributions play out against big changes and how apps are coming out onto mobile platforms, so we’re lucky in that I think we can see around the curve pretty well because organizationally that’s what we cover. We’re in a good place to be first to the punch in a lot of places. [Vox Media CEO Jim] Bankoff always tells me that for The Verge, the medium is the message, and we need to invent it first. Our jump into platforms is deeply informed by what we do editorially.

I had to report that post out because I didn’t know all the stuff, because there is a wall between editorial and revenue here. I’m very happy that wall exists, but as we look at the platform opportunity, the demand that’s going to be placed on every publisher who tries to participate in the distributed world is finding ways to do organic, meaningful integrations without corrupting our editorial.

It’s probably the hardest problem. It’s a problem that expresses itself in 10,000 different ways. Is the language on editorial sponsored content going to be “presented by” or “supported by”? Where do logo bugs appear on the videos? Do they make everything seem like ads instead of editorial that has a logo bug? There is a lot of work that needs to be done. There is a lot of training of the audience and setting of audience expectations that needs to be done. There’s a lot of respect for what both teams are doing that needs to be had in order to be successful at it.

None of it is solved. We’re in a good position to solve it because we do have a lot of respect for different teams. Again, The Verge is able to see the turn pretty easily because of what we do editorially, and we are particularly fortunate that our audience wants us to experiment and wants to give us feedback on what the future of media should look like. We can do wild stuff and ask our audience if they like it, and they will tell us sincerely if it succeeded or failed.