Last month, a fire tore through an iconic Tehran high-rise building, killing more than 20 firefighters and injuring another 70 people as it collapsed.

The fire made international headlines, but it was a particularly important story for BBC Persian, the British broadcaster’s Persian-language service that targets Farsi speakers in Iran and neighboring countries.

Covering the story, however, presented a challenge: The Iranian government doesn’t permit BBC Persian reporters in the country, and official news agencies are often not reliable.

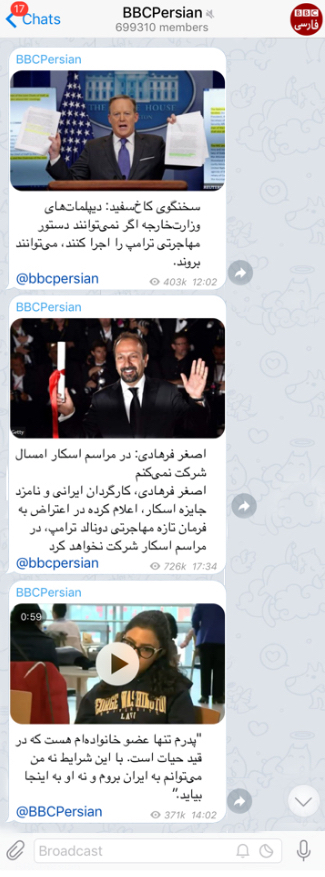

So BBC Persian turned to a different source: Telegram, the most popular messaging app in Iran. (It’s estimated that more than a quarter of all Iranians are on Telegram.) BBC Persian has more than 713,000 followers on its channel, but it also has a profile where users can get in touch with BBC Persian. After news of the fire broke, it asked its followers to share photos and videos of the fire.

So BBC Persian turned to a different source: Telegram, the most popular messaging app in Iran. (It’s estimated that more than a quarter of all Iranians are on Telegram.) BBC Persian has more than 713,000 followers on its channel, but it also has a profile where users can get in touch with BBC Persian. After news of the fire broke, it asked its followers to share photos and videos of the fire.

“That’s the main source of newsgathering at the moment for us,” BBC Persian multimedia editor Leyla Khodabakhshi told me from London. “The only way we could basically understand what is going on inside the country and get access to pictures was to put a call to action on different platforms and then receiving the UGC via our Telegram,” she said, adding that “lots of news agencies inside Iran have close ties to different political groups in the country, so you can’t rely on what you’re getting from the news agencies that are operating inside the country. We have to always crosscheck what we are receiving. That’s by putting different agencies together, but also to compare them to what we’re receiving from user-generated content as well.”

The Iranian Internet is heavily censored. Facebook, Twitter, and most major social platforms are blocked. BBC Persian’s website is blocked (and its TV broadcasts are routinely censored as well). Even though Iranians regularly use VPNs to circumvent government censorship, BBC Persian has turned to platforms such as Telegram that are permissible in the country in order to conduct reporting and promote its coverage to a wide audience of Iranians.

“This is a social circumvention strategy rather than a social media strategy,” Khodabakhshi said.

BBC Persian’s other main platform in Iran is on Instagram, which is the rare social network that is permitted in the country.

BBC Persian has significant followings on Facebook and Twitter, but it recently surpassed 1 million followers on Instagram, where its audience tends to skew female, Khodabakhshi said.

“Our strategy on Instagram is partly based on community building. It’s where we try to engage women to debate news on our page,” she said. “It’s not very straightforward, because it’s not a platform that is built for this type of debating or conversation, but it works for BBC Persian.”

There are, of course, limitations built into Instagram, though (it’s difficult to share links, for instance), and that’s why the Iranian government has decided — at least for now — not to block it, said Emad Khazraee, a professor at Kent State University who has studied social media and news consumption in Iran.

“I believe the Iranian government consciously left Instagram open because the affordances of Instagram are very limited,” Khazraee said. “You had a hard time to use it for social activism. They then herd them to one platform by letting it be accessible while blocking the other ones. Within Facebook, you have features, like organizing groups and having private groups, that you can manage to organize protests.”

BBC Persian puts most of its major stories on Instagram, Khodabakhshi said. And the account covers a wide range of stories — from Playboy’s decision this week to bring back nude images to Austria’s ban on full-face veils. It also uses Instagram to repurpose and promote BBC Persian television programs.

But because of the restrictions of the Telegram and Instagram platforms — along with Iranian censorship — driving users back to the BBC’s own platform isn’t necessarily a priority. Instead, Khodabakhshi said BBC Persian’s goal was to make as much information readily available as possible.

After President Donald Trump last month issued his executive order banning citizens of seven majority-Muslim countries — including Iran — BBC Persian went to work explaining the ban and its implications on each of its main platforms.

“We had to put the news in bullet points and push them on Telegram so people knew what is the latest and how Iranians are affected by this executive order,” Khodabakhshi said. BBC Persian also “visualized it and post it on Instagram without necessarily thinking that we need to have a referral back to our website, even though we have a detailed explainer on our website. That’s how it works in BBC Persian. We have to serve the audience.”

Messaging apps are popular among Iranians because they offer more privacy than more traditional social networks, Khazraee said. (But Telegram and other apps are still vulnerable.)

The beauty of messaging apps is that there is no API that you can go get user information from the system,” he said. “The max you might be able to do is to crawl all messages that are sent through a channel that is public, but you can’t get much information about who is using these channels. This is hard for us as researchers because it’s extremely hard to study this environment, but it’s extremely effective in terms of preserving users’ privacy.”

BBC Persian approaches Telegram slightly differently than Instagram and other social platforms. Though it shares video and other features on Telegram, the app’s chat interface helps BBC Persian view Telegram primarily as a breaking news tool, Khodabakhshi said. It sends about 20 messages per day.

When stories break, it’ll post news on Telegram and then also solicit comments and user-generated content as well, taking advantage of the less-public nature of the apps.

BBC Persian’s Telegram message about the death of former Iranian president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani was viewed 2.7 million times, for instance. And after Trump’s immigration ban was hastily enacted, BBC Persian asked its following on Telegram to share stories of how it was affecting them. It was then able to share some of those stories with other units within the BBC.“We have received hundreds of messages on Telegram about people who have been trapped somewhere, Iranians who have been traveling, those who were really concerned about the impact of the executive order on their lives. It has helped us give a more human personal flavor to our coverage. Not only for BBC Persian, but for the wider BBC as well.”

Telegram and Instagram are popular for now in Iran, but that could change if the government decides to restrict them or if users decide to change their habits. This previously happened to BBC Persian. In 2014, the service was planning to launch on the chat app Viber (which the BBC had previously used in other markets), but the government decided to block the platform. Users migrated to other services before deciding en masse to use Telegram, where the BBC eventually launched in late 2015.Ultimately, Khodabakhshi said BBC Persian is committed to publishing online to reach audiences in Iran, and it will continue to adapt as platforms and access changes in the country.

“We have always had to have contingency plans, Plan Bs,” she said. “If they shut down this platform, if they filter this platform — if they block Telegram, for example, all together, what would be our Plan B? We’re basically all the time on our toes.”