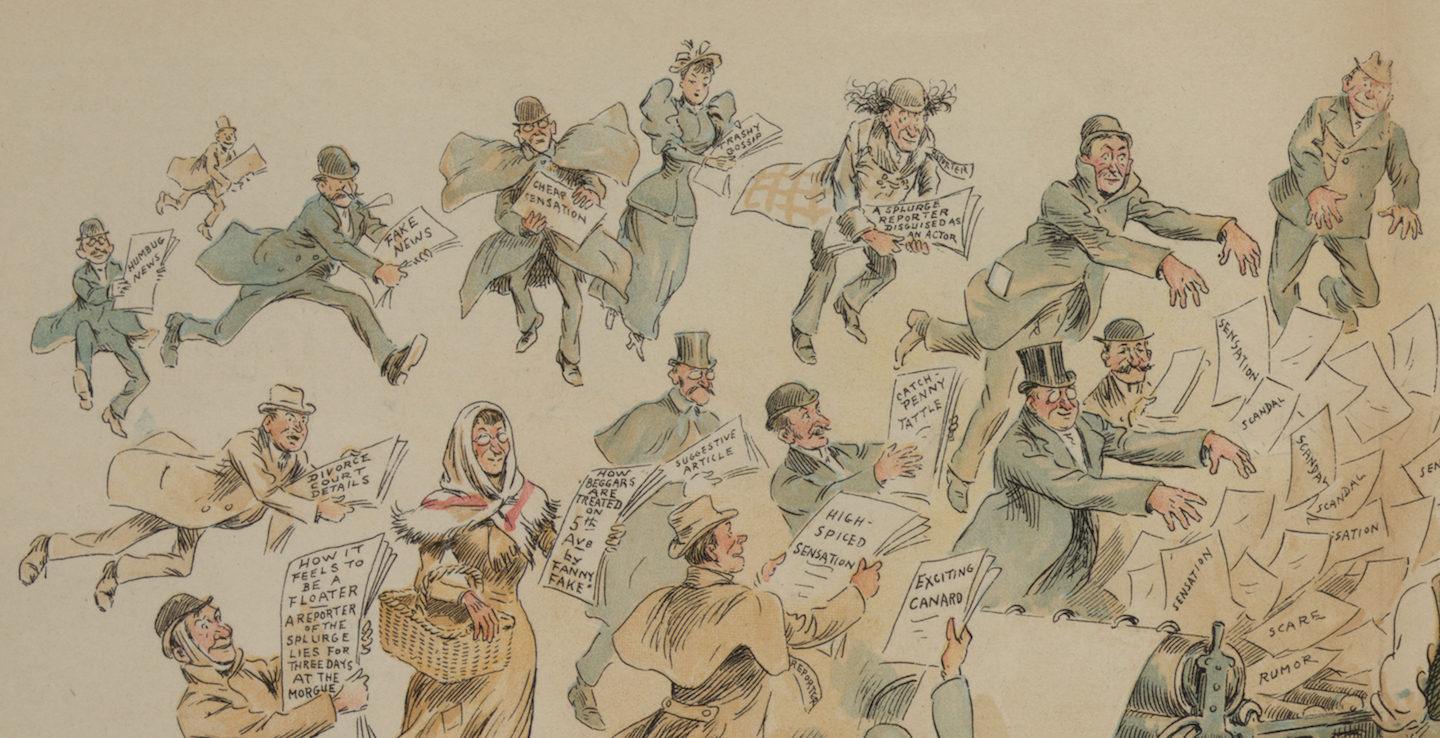

Fake news and news literacy and community engagement sometimes feel like new topics — and especially urgent ones, given nightmare-come-to-life incidents like Pizzagate.

But many people, including plenty in academia, have been plugging away at this line of work since well before Facebook had a fake news PR situation on its hands, before Pizzagate, before the 2016 U.S. election, before Facebook passed a billion active users.

Emerson College professor Paul Mihailidis, whose research covers topics like how young people consume information online and how people can use different forms of media to improve their communities, runs a new graduate program where students embed with partner organizations to develop concrete media projects that address specific problems that arise in local communities.

Emerson College professor Paul Mihailidis, whose research covers topics like how young people consume information online and how people can use different forms of media to improve their communities, runs a new graduate program where students embed with partner organizations to develop concrete media projects that address specific problems that arise in local communities.

“In doing civic media work, the first misconception is the thinking that a tool or a curriculum will necessarily solve anything. Students will jump to solutions before they understand problems,” Mihailidis told me, when I asked about common misconceptions among his students. “Fake news is a classic example here. We need to understand the problem, the community, why that problem exists within a specific community. That takes more time and energy than designing a response does.”

What we talk about when we talk about “media literacy” is often that teaching people to interrogate the credibility of media will help them sort out Pizzagate chaff from real news. But, as Mihailidis and his co-author Samantha Viotty wrote in a recent paper, there is a possible flipside: “[I]f individuals are taught to question, critique and inquire about the credibility of media, it seems as if this technique can justify those who felt compelled to investigate the #pizzagate story in the first place.”

I talked to Mihailidis about the new graduate program in civic media, his research on the ways information spreads digitally, the problem of labels like “fake news,” and the tendency toward “solutionism.” Our conversation is below, edited for length and clarity.

In our program in the fall, the students do problem framing. They look at concepts and ideas that inform civic media practice. They take a course in participatory methods, focused on how you do research with communities. We built a community IRB [institutional review board], focused on the notion of research as building community trust. Students take a design course. Through that process, they identify a problem area, a community stakeholder — they’re out talking to partner organizations.

After the first semester, the curriculum turns into design studios and elective areas, where students are learning specific skills or content areas — they might take courses in data visualization, or coding, or multimedia storytelling, whatever they think might inform their project. In the spring, they build prototypes, and in the summer, they work to test the impact of their prototypes.

We’ve been seeing a large growth in institutions building capacity around civic engagement. City governments are all starting innovation offices; more news organizations have community-focused roles. We noticed this in the nonprofit sector as well. We envision that the people doing the social media work over the past few years are necessarily going to become civic media practitioners, once the idea of using social media just as a communication device has worn off.

One student is working on a game-based project around fake news. The form of the game is still in its early stages, but it’s about making critical choices as you navigate online spaces. We’ve tried to push her away from just defining the problem as “fake news,” and more as, critical help in navigation of online information. One student is working with middle schoolers and storytelling, which he’s thinking about as a news and media education initiative.

In civic media, we look at a lot of what we do as rubbing up against the news and journalism area. We try to make those connections as intentional as we can.

In civic media work, the first misconception is thinking that a tool or a curriculum will necessarily solve anything. Students will jump to solutions before they understand problems. In a day of fast-paced information, given the speed at which technologies emerge and are distributed, students come into this program, have a million ideas for what they can do to help, before thinking about where problems originate, what the organization they partner with on their project does within the community.

Fake news is a classic example here. We need to understand the problem, the community, why that problem exists within a specific community. That takes more time and energy than designing a response does. The more we can focus on that, the better our responses are.Another thing we’ve seen: Work around digital media literacy that takes an intervention approach is messy. It takes a lot of iteration and refinement. The projects my colleagues and I do take years to get right, not months. With our grad students and the constraints of a 12-month cycle, they are interested in creating that shiny new thing, and the frustration is palpable, since there’s an urgency to their work.

So this paper talks about the spread of spectacle-based information. We use a few case studies and talk about the role of mainstream news in legitimizing the spectacle — for example, Pizzagate. Citizens can introduce and spread and perpetuate questionable information, and do so not because they aren’t media-literate, but because they have their own value system, and they’re trying to advocate for that: “Perhaps the U.S. electorate is not ‘ill-informed’ so much as they would rather find information that fits their worldview. If finding truth is not as large a priority as finding personally relevant information, then what good is knowing how to critique a message in the first place?”

We suggest that mainstream media sources, in doing their jobs as traditional information outlets, end up legitimating spectacle. It’s not anyone’s fault. It’s just digital culture, pushing up against traditional forms of storytelling and reporting.

We have another paper forthcoming on something we call the “civic actor gap.” We did a whole bunch of deep interviews with about 60 young people around the world, trying to investigate their perception of and engagement in civic, news-based processes. By young people, I mean 18 to 24-year-olds.

Young people are really good at sharing and promoting ideas they like and things that reinforce their value systems. But in terms of interrogation or stopping to do analysis, oftentimes, because of the peer-based nature of their networks, and because of the speed of the technologies they use, they end up stopping at the level of consumption, and using weaker forms of expression — liking, retweeting, resharing. Engaging critical dialogue, or providing their own sense of reflection on this, often doesn’t happen. That leads to perpetuating some of these false narratives we see emerging.

The News Literacy Project has been doing strong work in providing an outlet and resources for people to help them think about critical news consumption. But we’re only just starting to put these questions on the table.

There’s some benefit to dividing these terms. But at the same time, should we still think of news as a separate space, as a specific type of information? I would say there are far fewer things that are news-like about, for example, cable television channels, than there are about websites. These terms end up creating dichotomies, and people do interesting projects under them. But they also create issues. We see this with the “fake news” term too — by calling something “fake news,” for instance, are we legitimating the thing itself? We are saying there is something newsworthy about it.

In the latest paper I’ve been working on, I’ve been using the term “media literacies,” plural, in an attempt to not get caught in this trap of using one type of literacy over another type of literacy.

At our program we use “civic media,” because we have this idea of it as the technologies, practices and designs that facilitate the process of being in the world with others, toward a common good. It’s important that we’re not trying to silo out news, politics, data; that we allow them to all live in this ecosystem of how we design, whether that’s curricula or technologies. That’s a broad term, but it allows us to fit things into it. When people are creating news aggregators, public data initiatives — is a public data initiative a news literacy initiative, or a data literacy initiative? It’s both, neither, and all. I’m sorry I don’t have a pithy two-sentence answer for you here!