OSLO — Yes, there’s even a Trump Bump in Oslo.

Take 56 million, the number of views VGTV has gotten so far on its “satirical masterpiece” of “tupéfabrikk,” the company’s discovery of Donald Trump’s secret wig field in Tromsø, Norway’s Arctic Circle city. But that bump is just a collateral benefit of VGTV’s innovation engine.

In the three and a half years since its founding, VGTV has become a global model, with its leaders speaking at numerous media forums.

This spring, the latest spun-off Schibsted division passed an important milestone: VGTV, the video operation of the leading Norwegian daily VG, now produces more monthly advertising revenue than does VG’s seven-day print product. VG, like many dailies, is losing double digit percentages of print revenue each year, but that revenue loss is being made up by the video operation. Of course, the new money is not nearly as profitable as the old — but for Schibsted, it’s all about the all-in bet on the longer-term digital future.

“What I hear [from journalists at conferences] is that people get inspired…that we are optimistic of the fact that we think we are going to manage to monetize video,” explains Helje Solberg, VGTV’s CEO and editor. Solberg moved over to VGTV more than three years ago, after serving for nine years as VG’s executive managing editor.

In 2016, VGTV pulled in 83 million Norwegian kroner, or about $10 million in total revenue. Into early 2017, it’s now seeing a steep ramp in growth, with a 51 percent increase year over year in the first quarter.

It’s not simply a maturing of the market — it’s audience growth. Year over year, VGTV grew audience 29 percent, accounting for 420,000 daily unique users in the first quarter. It can count more than 25 million video streams started per month, or almost a million a day.

That’s a good number given the sparsely populated northern terrain — Norway’s only got 5 million people.

Given that small, well-read population, why do so many publishers buttonhole Solberg at media events?

First and foremost, it’s the unique story of Schibsted’s serial and widening innovation. Schibsted is the biggest publisher most other publishers have never heard about. Based in Oslo, with strong newspaper publishing positions in both its home country and Sweden, Schibsted has become a Top 10 global company in revenue among legacy news providers, with operations in 30 countries and three continents, employing almost 7,000 people. As one executive of the now hyper-innovative Washington Post recently told me: “We like Schibsted. Some smart people there.”

Today, Schibsted’s media houses (publishing) contribute about 25 percent of its overall revenues, with the company’s marketplace/classifieds business and “growth” divisions still generating good growth. (We’ve chronicled Schibsted here at the Lab for years.)

It’s the innovation at Schibsted’s media houses that compels attention — for its early impact, its restructuring, and its results, with VGTV only the latest installment. The most recent critical result: Schibsted’s Norwegian news businesses now show small growth. In the first quarter, revenues were up 4 percent, with earnings (EBITDA) up 8 percent.

Overall, for VG (a popular Oslo daily, which operates alongside Aftenposten, Schibsted’s “quality” daily), the numbers show that investments in innovation are paying off. In the first quarter, VG saw 27 percent growth in digital subscribers (to 108,000) and a 28 percent growth in digital advertising, a good amount of that attributable to VGTV. Another good print-to-digital crossover number: Operating expenses were down 7 percent.

As it crosses over, the video strategy fits well with Schibsted’s vision of a next-generation platform vision. That plan emphasizes a signed-in engagement that seeks to compete against the always-signed-in world of Facebook.For innovation watchers, the short story of the Schibsted model is clear: Transforming the news business means separate and reintegrate, separate and reintegrate. That’s what Schibsted did in 1999 when, ahead of its peers, it funded a separate — and competitive to print for audience — digital operation. Later, it did the same with mobile.

Then, in late October 2013, it applied the successful model once again, to video and VGTV. Both “digital” and “mobile” have been folded back into the VG mothership. Solberg says she expects that VGTV will be soon as well. Once innovation is well enough established, resourced, and acculturated, it folds back into a bigger, smarter, and now digital savvy newsroom and company.

Today, VGTV includes a staff of 65. They remain organizationally separate from VG, though the operation is housed in the VG offices and works often as if the two are one — which is the point.

When I first wrote about VGTV three years ago, then-VG CEO and editor Torry Pedersen told me of this and other Schibsted forays: “Make sure you lose money for at least three years.” In fact, VGTV first became profitable in April, a few months past its three-year anniversary, says Solberg, though she doesn’t expect 2017 to be in the black overall.It’s telling that both Solberg and Pedersen have held both top editorial and business-side titles simultaneously. The Schibsted model seems to recognize and promote shapers, and some of those shapers should come from the editorial side of the business as well. Earlier this year, Pedersen, well known and respected in the broader media world, became head of Schibsted’s media house businesses in Norway overall.

In those three years, Solberg, a long-time VG news executive, has learned lots about what works and what doesn’t in digital video. She’s now intent on better integrating the VGTV experience into VG’s wider news delivery, and wants to apply lessons from its Snapchat and Facebook tests.

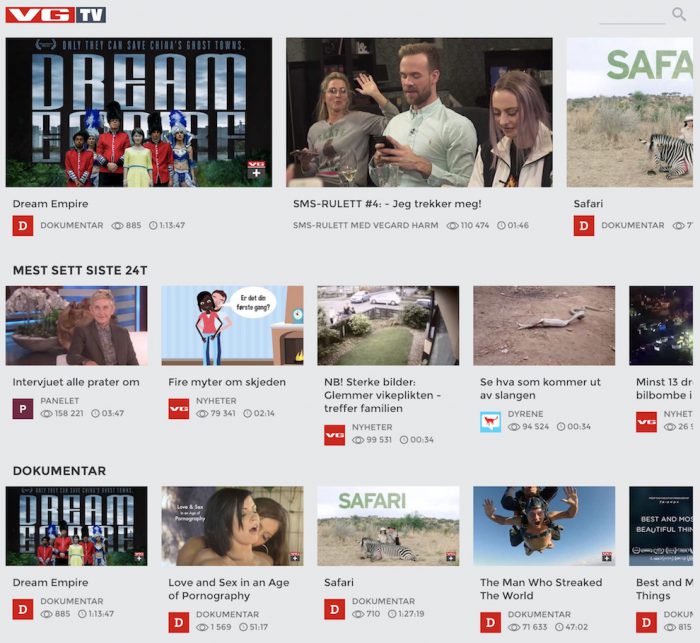

She’s had to make ongoing decisions about the kinds of video VGTV emphasizes. The site offers a lively mix — its offerings translate fairly well with Google Translate — of news, interviews, and popular culture. News and sports lead viewing time, with a variety of other programming, created and licensed, filling out the picture.

Given VG’s overall pre-eminence as a breaking news site, VGTV prizes its advances in live programming. “In the terrorist attack in Belgium last year, it was the first time we documented a major breaking news story with live images before still images,” she says. “Now, that happens again and again. On U.S. election day, more people followed our live coverage than read the most-read article on VG.no.”

For global coverage, VGTV uses both wire services and its own correspondents, transmitting live images from the news spot. Its anchors also host news programs.

“We don’t necessarily go live every day,” says Solberg. “It’s very important for us to go live if there is news that we have to report. All we need to go live is a journalist and an iPhone. The technology works with us. It’s easier and easier to go live.” By the numbers, viewers responded, with “live” viewing more than quadrupling in 2016 over 2015.

At this point, somewhat surprisingly, more viewers watch VGTV on their desktops than on mobile, though in April, mobile topped desktop. Why is desktop so strong? Solberg believes getting the mobile user experience right is one of her greatest challenges. A prime goal: “integrated native video.”

“We need to integrate video much better into the news journey. I used to say that you have peer-based video, [where] users go to the platform to watch video, [and] push-based video. Users go to the platforms again to get updated. Both are served video seamlessly like Facebook. For us, the big question is: Is it possible to challenge the peer-based platforms such as YouTube, that established play channels on time spent? We think we need a different approach. Facebook did some smart moves — it’s muted, it goes very fast, it has no ads interrupting the content — while we have a click-to-play model and interrupting ads.”

So, Solberg’s team studies Facebook, and its new partner, Snapchat. VGTV began producing VG’s first-in-Norway Snapchat Discover channel in January. “Snapchat is a good place to learn and experiment what makes a good video on the mobile phone. We really like it as a place to publish stories. It’s also a good carrier of advertising. It remains to be seen, however, how easy or how difficult this will be to monetize. It’s still an investment case for us. The test period for six months was sold out within two weeks.”

In its short history, VGTV has managed to gain healthy ad rate for its video ads — a CPM of 180 kroner, or a little more than $20. That’s better than VG’s average non-video digital ad yield, says Solberg.

Digital video ads come out of digital ad budgets, she says, so in this arena, VG is up against Facebook and Google. Together, the two dominate Nordic digital advertising, with a two-thirds share of the market.

At this point, 15-second pre-rolls predominate, but VGTV is experimenting with shorter forms less than 10 seconds.

“It is possible to tell a story, even in six seconds,” she says. Storytelling is key: It’s noteworthy that, along with VGTV’s increased ad revenues, it’s branded content that has also helped make up for print losses. Initiatives such as The New York Times’ T Brand Studio have found that combination of branded storytelling and video, the virtuous mating of two post-display ad formats.

Solberg hopes to find other ad rhythms that work, just as VGTV is doing editorially. “We saw two years ago most of the clips were, like, two and a half to three minutes. Now they are less — about one minute. But the time spent on VGTV has increased. So we make shorter news videos, but people spend more time with us. We also have a higher completion rate,” says Solberg. “We make the short videos and then we make the longer videos and documentaries and programs.”

“It’s possible to tell a smart story in 43 seconds,” says the former political journalist. She shows me one video — a quick-moving, graphics-centric piece, one that indeed tells its story well in less than a minute.

Very short, or longer and explanatory. The web isn’t a medium medium.

For long-time print journalists like Solberg and Pedersen, “TV” learnings have opened unexpected doors. Yet, all the efforts remain focused on a singular goal, which Solberg puts simply: “If VG is to keep and strengthen our No. 1 position as Norway’s largest online news site, we need to succeed with video.”

As it strategizes, VG also makes interesting use of old-fashioned linear TV. VGTV runs several channels on cable and satellite and gets payments from companies for carriage. Solberg is quite clear that Oslo’s two major TV news providers — commercial TV 2, and public broadcaster NRK — will remain the near-term linear TV choice of consumers. As strong as VG is for breaking digital news, consumers haven’t transferred that habit to old-fashioned TV. “What we learned was that, when there is big news happening, people go to VG, digitally, and to established TV channels. That didn’t turn out — that people would also watch us on linear TV,” says Solberg.

How likely is that to change? “I don’t think that’s possible to change,” acknowledges Solberg. “We have said from the very beginning with the linear TV channel, that everything we do has to gain us digitally. Our core strategy is digital.”

And that strategy includes ad revenue that is now “broadcast,” even if current VGTV revenues largely are bought out of the digital bucket.

“Traditional TV is still very strong in Norway,” says Solberg. “Norwegians like TV and watch almost three hours a day on linear TV. I think it’s just a matter of time before this shift [to digital video] in consumption will pay off.”

Put it all together and linear TV is a means to VG’s digital end. Those cable and satellite distribution payments represent the majority of linear TV revenue, with advertising a secondary source there.

After testing news on linear TV, VGTV now runs largely documentaries on the channel around the clock. “It’s about six to eight documentaries a day,” says Solberg. “Some news — a news loop and a sports loop.”

Intriguingly, it is these same documentaries — about 20 were produced last year — that have now moved behind a digital paywall. Documentaries such as “Stuck,” a series on human trafficking, used to be largely free via the web; now they support that significant digital subscription growth. And yet they remain free on VGTV’s linear channel. Consumer confusion? Not really — just a different distribution channel.

As VG and Schibsted’s other dailies in Norway and Stockholm work through the possible delivery channels of 2020, they have to deal with the economics of 2017. How well is that big overall strategy going — the establishment of VG, a brand established out of the ashes of World War II, as a digital brand of today and tomorrow.

In 2017’s first quarter, digital revenues — including VGTV’s — totaled 48 percent of all VG income. That’s close to a real crossover, and the highest percentage of any daily-based operation of which I’ve heard.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story said that VGTV was generating more revenue than VG’s print edition. In fact, it is only generating more advertising revenue than print — if you include circulation revenue, print is still ahead. We regret the error.