The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

The conservative Weekly Standard joins Facebook’s fact-checking network. Conservative magazine The Weekly Standard, which has run a fact-checking column for several years, has become the first right-leaning outlet to join Facebook’s fact-checking initiative. (Quartz had reported in October that this was going to happen.) Sam Levin, who’s been following Facebook’s fact-checking efforts for awhile, reports in The Guardian:

Weekly Standard will be the first right-leaning news organization and explicitly partisan group to do fact-checks for Facebook, prompting backlash from progressive organizations, who have argued that the magazine has a history of publishing questionable content.

Facebook’s other fact-checking partners, who are all members of Poynter’s International Fact-Checking Network (a group that Weekly Standard joined), do not explicitly identify as liberal (or any other ideological stance), while the Weekly Standard describes itself on its own site as a “weekly conservative magazine & blog.”

As with any verified signatory, TWS Fact Check (https://t.co/QuPEfVTMZ4) went through a vetting process whose assessment is public at https://t.co/8CFLiZIM82

— Alexios (@Mantzarlis) December 6, 2017

The Guardian has a roundup of the backlash, mostly coming from Media Matters for America, a watchdog group that focuses on conservative misinformation. The partnership “makes little sense given the outlet’s long history of making misleading claims, pushing extreme right-wing talking points, and publishing lies to bolster conservative arguments,” Media Matters posted on its blog.

But Stephen Hayes, the editor-in-chief of the #NeverTrump-aligned Weekly Standard, told The Guardian, “I think it’s a good move for [Facebook] to partner with conservative outlets that do real reporting and emphasize facts. Our fact-checking isn’t going to seek conservative facts because we don’t believe there are ‘conservative facts.’ Facts are facts.”

“We are trying to raise standards for fact-checking across the industry. The more organizations meet these basic criteria of transparency, the merrier,” Alexios Mantzarlis, head of the International Fact-Checking Network, told me.

Integration of conservative media into collective fact-checking is an important step. It diversifies the process (conservatives see things liberals don't) and can persuade disaffected conservative readers/viewers that the MSM isn't fake. https://t.co/fDDUTJbxEI

— Will Saletan (@saletan) December 7, 2017

Reminder: It’s unclear whether Facebook’s fake news identification program, which consists of layers upon layers of outsourcing, is actually accomplishing anything meaningful. Facebook claims that it is working, but the fact-checking partners themselves have a lot of complaints.

A bunch of research shows that fact-checking has come to be regarded as a liberal concept; more here and here.For many reasons, Facebook can't continue to outsource the moderation of its own content. It allows the platform to be hijacked by the optics of partisan grievances in exchange for the optics of false neutrality.https://t.co/jb4D8Cet5A

— Daniel Sanchez (@danieljsanchez_) December 6, 2017

“Political information transmission as a game of telephone.” How does political information change as it’s passed from person to person? In a paper published online in the Journal of Politics, Taylor Carlson, a Ph.D candidate at the University of California, San Diego, explains her experiment, which she did using Mechanical Turk:

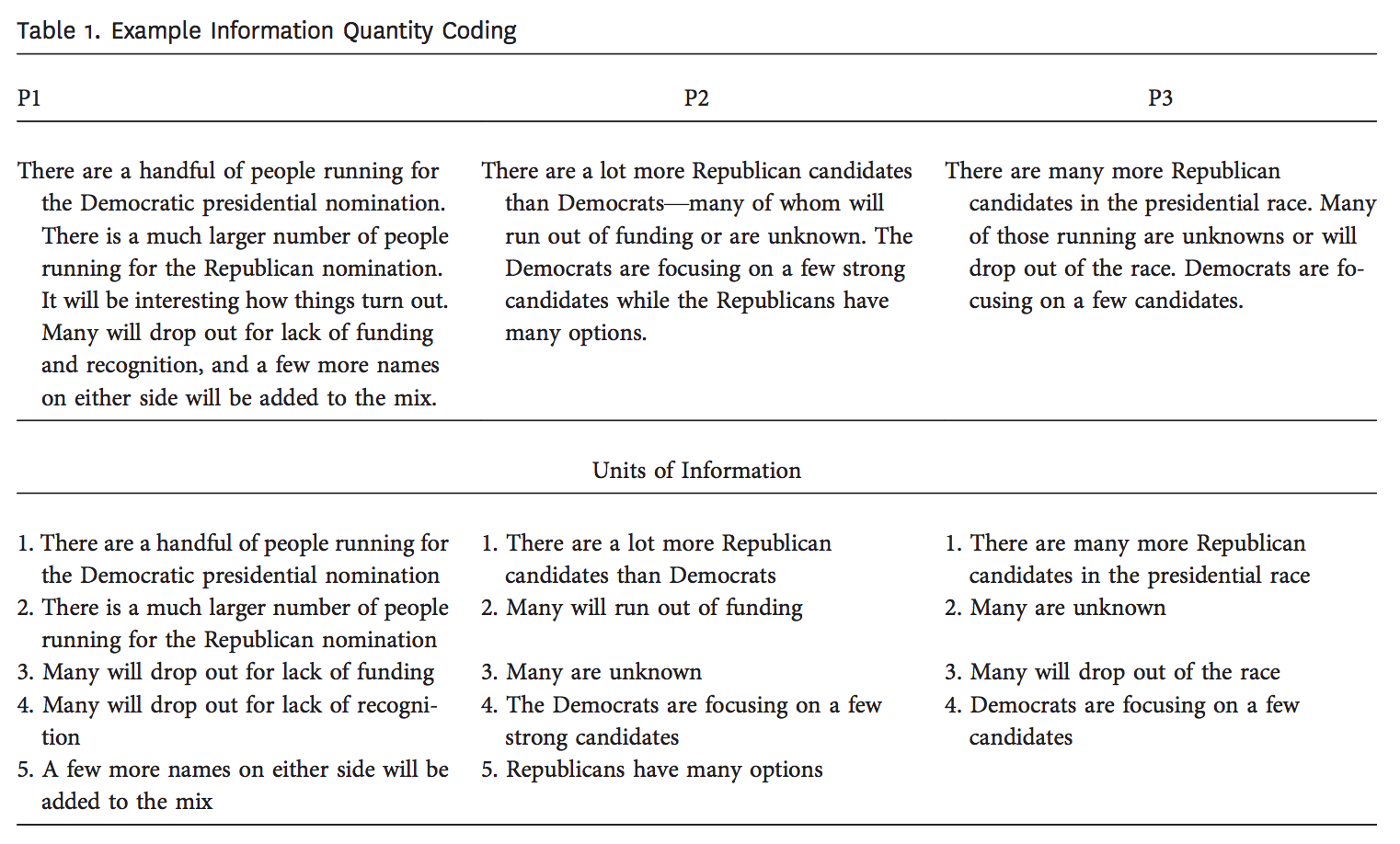

A diffusion chain consists of three unique participants that attempt to inform one another about the 2016 presidential candidates. The first participant (P1) read an article about the 2016 candidates as if he or she was trying to learn about the candidates. After they read the article, the next screen prompted the participants to write a message to people with whom they have previously discussed politics, elections, or current events, telling them about the 2016 presidential candidates. The next participant (P2) then read P1’s message about the candidates and was asked to write a message under the same instructions. Participant 2’s message was then given to a third participant, P3, to read, and P3 was asked to write a message under the same instructions. All participants were blind to any characteristics about the people from whom they received messages and to whom they sent messages. This provides for a baseline test of information diffusion, net of strategic communication or discounted interpretation conditional on individual characteristics.

The amount of information in each message declined as it was passed along; “The people at position 1 passed on only about 3 percent of the information from the article to the next person.” Here’s one example:

Carlson also looked at “the cumulative distortion of the information across each chain.” While information was distorted, it was rarely totally wrong. “Individuals at the end of a chain are certainly not exposed to the same, as much, or as precise information as those at the start of a chain, but they do not appear to be any more likely to be exposed to blatantly wrong information.”

See also The amplification of risk in experimental diffusion chains (PNAS 2015): "Although the content of a message is gradually lost over repeated social transmissions, subjective perceptions of risk propagate and amplify due to social influence." https://t.co/8KHpRmoHJ7

— Brendan Nyhan (@BrendanNyhan) December 5, 2017

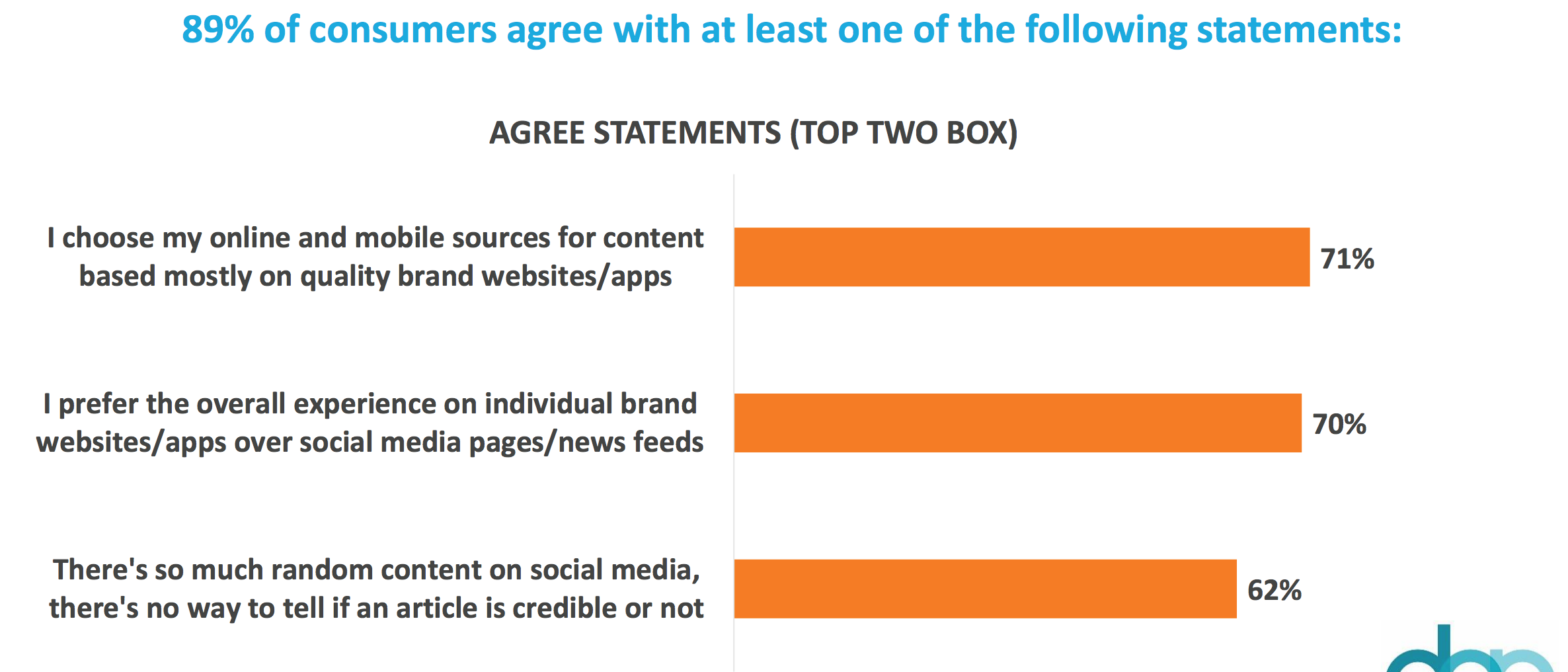

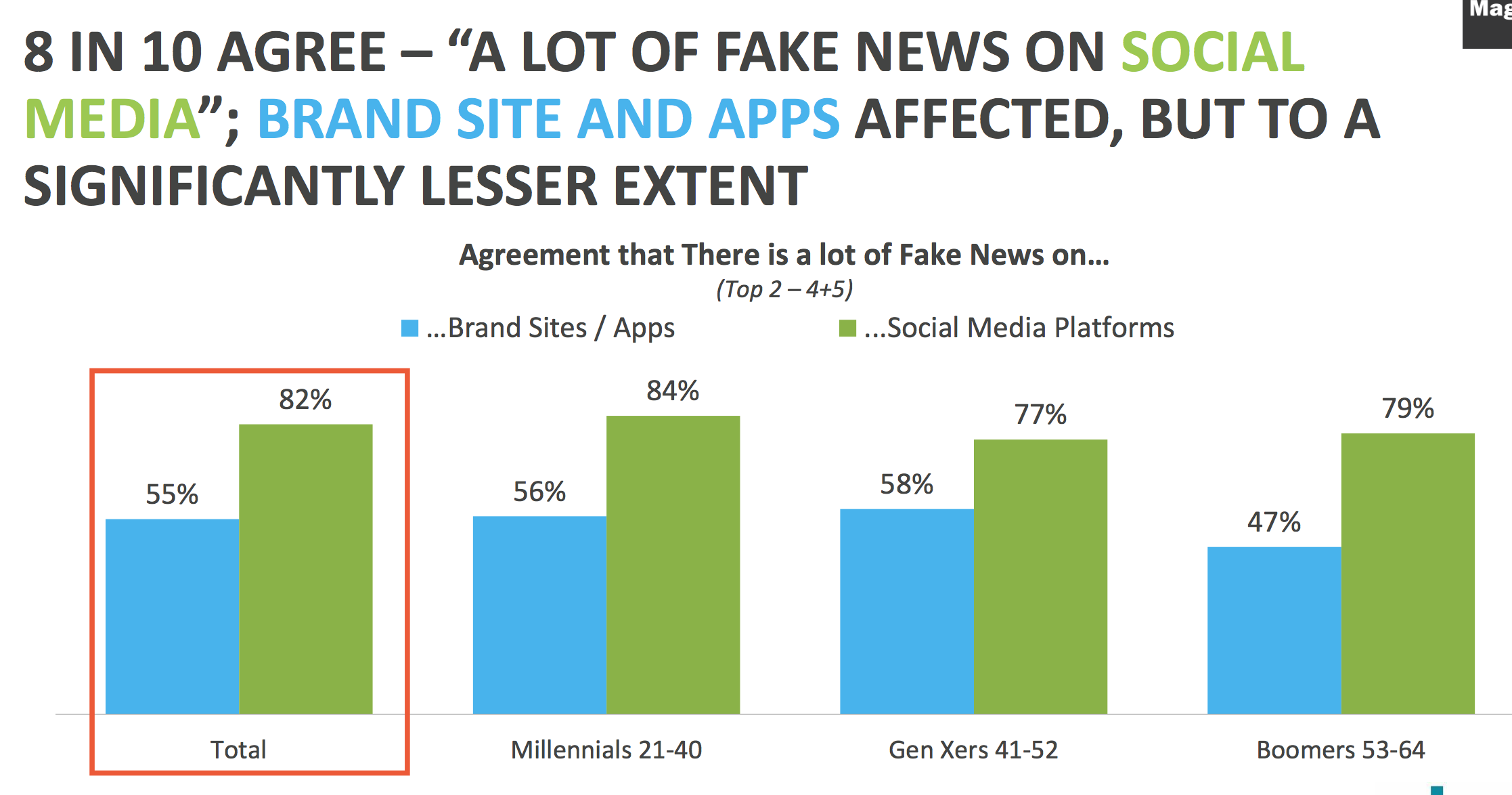

“Premium preferred, social skeptic”? New research from Digital Content Next, the trade association for digital publishers, released a new report on trust in digital media that finds that people are more likely to trust content on a brand’s own app or site than on YouTube or social media.

The research shows “a measured and significant decline in trust for digital information discovered on Facebook and YouTube,” writes Jason Kint, CEO of Digital Content Next. “It’s a problem that no one wants to talk about as it puts us at direct odds with the most powerful companies on the planet. But it’s real. And it’s a real problem for the whole industry.”

hint: social media = Facebook and this is their problem. pic.twitter.com/sNZqJWMA3J

— Jason Kint (@jason_kint) December 7, 2017

The fact that the gap expands with millennials is “counterintuitive,” Kint noted to me. “We often wrongly believe millennials are more whimsical about things like privacy, security and trust, when often they’re even more diligent and careful.”

It’s clearly a huge group, encompassing 89 percent of the people surveyed. Of course, what people say they think about content online and what they actually do with content online are two different things. Still, the survey found that, of this group:

— 61 percent are under 40

— 44 percent currently pay for a subscription to a brand site/app

— 71 percent visit brand sites/apps often in an average week

— 68 percent purchased a product based on an ad they saw online in the last 30 days

The survey also asked respondents about what breaks their trust.

DCN commissioned the research in October 2017; the online survey included 1,000 people in the U.S., ages 18–64, who have a home internet connection and said they engage with social media and brand sites or apps weekly or more.