The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

Last week, the global policy nonprofit RAND Corporation released a 300-page report — it’s a book — entitled “Truth Decay: An Initial Exploration of the Diminishing Role of Facts and Analysis in American Public Life.” The report defines “truth decay” as a set of four related trends (of which fake news is only a little part) and offers lots of ideas for future research. It’s focused on the United States, though “there is evidence that this phenomenon is also occurring elsewhere, especially in Western Europe.”

One of the ways in which I find the RAND report most useful is that it highlights throughout where research is still needed — what the big questions still are. The authors reviewed more than 250 articles and books that fit into the Truth Decay framework; you’ll find all the buzziest studies and academics mentioned here. But, they say, there’s still so much more we don’t know. If you’re looking for something to study, you’ll find so many ideas here.

Authors Jennifer Kavanagh and Michael D. Rich define truth decay as:

1. increasing disagreement about facts and analytical interpretations of facts and data

2. a blurring of the line between opinion and fact

3. the increasing relative volume, and resulting influence, of opinion and personal experience over fact

4. declining trust in formerly respected sources of factual information.

It’s not just fake news, and, as Kavanagh and Rich note, plenty of sectors of American society — the military, the technology industry, sports — are increasingly relying on facts and data as “essential to survival or necessary for success. Why aren’t national political debate and civil discourse following this trend?

Many observers and analysts have responded to these trends in the political environment by arguing that global society has entered a “post-fact” world or by focusing on the spread of “fake news,” broadly defined. We believe that the argument is inaccurate and the focus is misplaced. First, as noted earlier, facts and data have become more important in most other fields, with political and civil discourse being striking exceptions. Thus, it is hard to argue that the world is truly “post-fact.” Second, a careful look at the trends affecting the U.S. political sphere suggests that such phenomena as “fake news” are only symptoms of a much more complex system of challenges, one with roots in the ways that human beings process information, the prevailing political and economic conditions, and the nature of the changed media environment. “Fake news” itself is not the driver of these deeper questions and issues, and simply stopping “fake news” is unlikely to address the apparent shift away from and loss of trust in data, analysis, and objective facts in the political sphere. As a result, a narrow focus on “fake news” distracts from a rigorous and holistic assessment of the more-extensive phenomenon—an assessment that might lead to remedies and solutions.

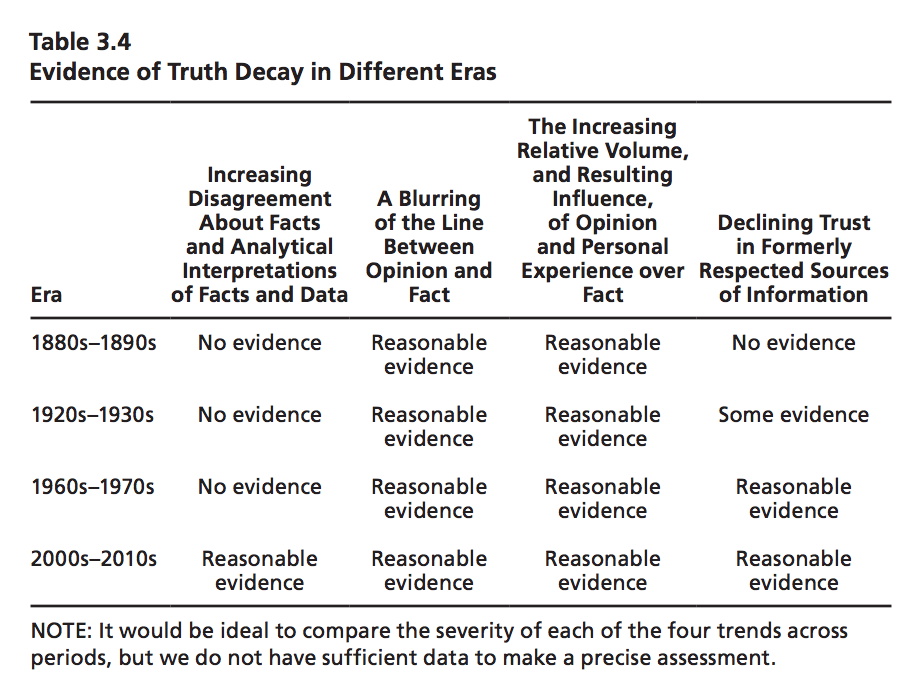

What’s changed, why, and how is our time similar to or different from the previous historical periods that are often mentioned when people point to the yellow journalism of the 1890s and say “we’ve been through this before”? The authors suggest that what’s different about now is our “increasing disagreement about facts and analytical interpretations of facts and data.” For example:

[W]e refer to increasing disagreement in areas where the prevailing understanding has not changed, or where it has even been strengthened by new data and analysis. Examples include skepticism about the accuracy of basic statistical information, such as the unemployment rate or the demographic makeup of the United States. It also refers to increasing disagreement or doubt about the interpretation or analysis of data and statistics in areas where supporting evidence has not changed or has strengthened, such as the science supporting the safety of vaccines.

The year 2000-ish appears to be some sort of turning point. In 2001, for example, 64 percent of respondents to a Gallup poll said that it was “extremely important” to get their children vaccinated. In 2015, 54 percent of respondents said so, and the shift was “significantly greater among specific demographic groups, including younger parents.” We see the same trend when it comes to beliefs about violent crime in the United States:

Data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics show a steady decrease in violent crime rates since 1993. Attitudes about whether there is “more crime in the United States than one year ago,” however, have not followed this same trend. Attitudes tracked closely with reality, as measured by the trend in violent crimes committed per 1,000 persons (over 12 years of age), until about 2000. After this point, agreement that crime rates in the United States were declining began to erode, and an increasing number of respondents reported that they perceived more crime in the United States than in the previous year, despite clear evidence to the contrary. In other words, an increasing number of respondents question existing data on trends in crime even as data collection and documentation methods become more advanced.

Trust in major institutions, too, has dropped sharply over the past 20 years.

The authors look at three previous historical periods in depth and find “the least evidence that previous periods considered in this report experienced the same eroding agreement about facts and analytical interpretations of those facts that appears to be occurring in contemporary society…this is an important distinction between the current period and previous eras.

It’s possible, they write, that “the end of such phenomena as Truth Decay occurs naturally, in a sort of cyclical or wave-like process.” But if that’s the case, it’s not clear how we get out of the cycle.

One thing that simply hasn’t had enough time to change, probably: “Cognitive biases and the ways in which human beings process information and make decisions.” These are “common and consistent characteristics of human cognition.” But cognitive bias is an essential part of all of this:

Cognitive biases can…be exploited by any of the agents of Truth Decay described in more detail at the end of this chapter, including international actors, researchers, partisans, and propagandists. Furthermore, it is not clear that Truth Decay would be as dangerous or persistent absent these characteristics of human cognitive processing…

Cognitive bias might be a latent driver — a factor that is always present but does not cause Truth Decay unless activated by other environmental conditions and factors or exploited by actors with specific political and economic motives.

They recommend a couple of areas of future research into cognitive bias:

Research in this area could include an assessment of the types of messages or messengers that tend to be most successful in reducing cognitive biases, or an analysis of the issues on which cognitive biases are easiest to successfully challenge. As noted earlier, research into ways to reduce cognitive bias that could be tested and implemented outside of a traditional laboratory setting would also be valuable. Such approaches might include efforts to establish and disseminate standards of objectivity and evidence in structured decisionmaking situations, such as jury deliberations. Other useful exercises would be to (1) formally assess the ways that technology exacerbates cognitive biases and the ways it might challenge or undermine them by altering some of the basic assumptions on which social or other relationships are based and (2) explore whether there are ways to more precisely understand and even measure the costs to a person (e.g., in terms of reputation or social stigma) when he or she changes his or her mind and whether it is possible to design incentives that offset these costs.

The Annenberg Public Policy Center, for instance, has a project on the “Science of Science Communication” about how scientific findings can be conveyed to the public “in a way that is both more understandable and more persuasive, with the aim of closing the gap between scientific knowledge and research findings and public beliefs on such issues as the safety of vaccines and GMOs.”

In the book’s final chapter, Kavanagh and Rich lay out a bunch of questions for future research. Here are some:

— When are people most susceptible to disinformation, and can they be “inoculated” against it?

— How does a shift toward online political activism and engagement affect democracy?

— How has social media contributed to a decline in trust in institutions and increasing disagreement about facts?

— How can we get better data on discourse and engagement? For example, we could analyze the “quality and tone of discourse” at town hall meetings across states, or in congressional debates.

— Has the amount of disinformation and misinformation available actually increased over time? It certainly seems as if it has, but “empirical evidence to support such an assessment is limited.”

— How could we increase public demand for fact-based information? Would incentives work?

Moving forward, the RAND Corporation plans to continue investigating three areas: “the changing mix of opinion and objective reporting in journalism, the decline in public trust in major institutions, and initiatives to improve media literacy in light of fake news.'” Media literacy will be its first area of focus.

The full report is here.