Is it really only the beginning of March? The news business’ gyrations seem to be moving at warp speed this year, and particularly this week, as two newspaper companies long in the news make new big moves.

As Tronc reckons with the crash of its stock price and oh-so-private Alden Global Capital gets publicly accused of financial irregularities, the plot of who will own America’s newspapers companies just thickens.

Let’s look at the big questions arising out of the Tronc and Alden news, and a few others generated by this remarkable news week.

From a January high of $21.55, Tronc shares closed at $15.05. That’s 30 percent down in total.

Why? It’s always tough to pinpoint investor rationale. In this case, though, three factors seemed to drive the crash.

First, the company’s financials themselves. Its adjusted earnings per share fell by more than 35 percent year over year, and overall revenue looked down by almost a tenth.

Second, the company, oddly, offered little “visibility” into how it would perform this year. That’s de rigueur on such quarterly analyst calls.

Instead, Tronc CEO Justin Dearborn surprised the call’s four analysts by saying: “Looking ahead to the remainder of 2018, given the pending material divestiture [the L.A. Times sale]…we are going to deviate from our normal practice of providing a financial outlook for 2018. We anticipate providing it on our first quarter 2018 earnings conference call as we have a better understanding of the impact of our recent actions on full-year performance.”

In other words: We haven’t yet figured out how Tronc will perform financially without the Times and San Diego Union-Tribune. Or alternatively: You wouldn’t like what we’d have to tell you.

Third, it failed to answer several questions from the analysts on the call. Read the call transcript, and you can see the analysts pushing for answers on the business ahead, the impact of tax changes, and even the performance of the recently purchased New York Daily News. Further, analysis of Tronc’s performance was made more difficult by the need to account for a “53rd week” in the fourth quarter, something the calendar forces them to do every few years. Most newspaper companies have broken out both a 53-week and 52-week comparison on their key metrics, but Tronc’s such reporting was limited.

Doing the math, Tronc appears to be down 9.6 percent in overall revenues year over year, on a “same-store basis.” That puts it no better than the middle of the pack of its newspaper group peers.

The fourth quarter posed particular issues — and no surprise, sources tell me, the circus at the L.A. Times exacerbated ad sales.

In that fourth quarter, Tronc was down 19.7 percent in its print ad revenue. Circulation revenue was down 3.5 percent. TroncX, the company’s digital division, was up 1.4 percent in revenue. (These results all reflect close-to-apples-to-apples 2017 to 2016 comparisons, with that 53rd accounting week of third and fourth-quarter financial contributions of the New York Daily News removed.)

Overall, analysts found themselves unpleasantly perplexed, and we have to believe that their investor advisories helped send Tronc shares tumbling.

If the numbers and the lack of outlook were surprising, the bigger questions may have sounded an alarm with the investors who had bid up the stock since September. That question, in a nutshell: What’s chairman Michael Ferro’s strategy now, after selling the California papers?

On Feb. 7, as it announced the Times’ sale, Tronc said it was “embarking on a national digital growth strategy through its newly reorganized Tribune Interactive division.” On Thursday’s call, again oddly, there was no mention of the Tribune Interactive push, or of its leader, the newly reinstated Ross Levinsohn, the just-departed L.A. Times publisher.

That digital strategy also now includes more promises of newsroom transformation.

According to Poynter’s Rick Edmonds’ well-detailed piece, “the company is launching big plans to get its editors and reporters pivoting to digital.” Yes, pivoting to digital in 2018, at a company that as Tribune had been an early digital innovator and that was renamed Tronc — short for Tribune Online Content — by Ferro two years ago.

Tronc’s strategy, of course, has been a moving target since Ferro took over the company, with a series of transformations promised and under-delivered. Instead, the company has been much more about deal-making in its short history. Just this month, Tronc lost its bid to buy the Austin American-Statesman (as did with Hearst) to GateHouse Media. Now, as I’ve reported that GateHouse will likely be the winner of the Palm Beach Post auction as well, Tronc is probably looking at another failed buy. It’s in the market for more digital properties as well, as I reported in February, including talks with The Street.(Last year, the Department of Justice thwarted its efforts to buy the Orange County Register and the Chicago Sun-Times. Tronc has been successful in buying the New York Daily News and a majority interest in the BestReviews shopping comparison site. )

Why are those losses significant?

When Patrick Soon-Shiong formally takes over as owner of the L.A. Times and San Diego Union-Tribune, a deal that is now likely to close before the end of the month, Tronc becomes a much smaller company. By various metrics, it will lose as much as half of its size. And to Ferro — who has talked about building a big national network — size matters. Tronc has long touted its march toward a national digital audience of 100 million; selling the Times puts it farther from that goal.

Secondly, the company finds itself confronted by “trapped overhead” costs.

Chains like Tronc routinely allocate the cost of corporate management to their properties. These headquarters costs — from top executive compensation to HR, finance, and other increasingly centralized functions — form a significant outlay for companies like Tronc with struggling financials. As the California newspapers disappear from Tronc’s books, so do their substantial payments to the mothership, their “allocated expense.” Now, Tronc needs more newspapers (or other properties) to help make up those lost payments.

Takeaway: For a company that is used to shooting from the hip, Tronc seems unusually tight-lipped. Maybe Ferro will pull another rabbit out of his hat — or maybe the market is turning on him.

That’s the allegation now moving into Delaware’s Chancery Court. This week, Solus Alternative Asset Management LP accused Alden Global Capital — the increasingly maligned majority owner of Digital First Media — of “possible mismanagement and breaches of fiduciary duty.” The big charge: Alden took profits from DFM properties and moved them into “poorly-performing investments.”

Solus asks for access to the books of Media News Group Enterprises Inc., the company through which Alden controls dozens of newspaper properties, including the Mercury News, The Denver Post, the St. Paul Pioneer Press, and Southern California News Group, all of which have been hit with major newsroom cutbacks as recently as this year. In fact, word is now out that The Denver Post, which saw its publisher suddenly resign in January, apparently over plans for further reductions, may soon be making another major newsroom cut, further decimating a newsroom of fewer than 100.Already, the suit alone has revealed new information about Alden and DFM operations. We’ve learned that Alden controls the company with 50.1 percent of its shares, while Solus holds 24 percent.

A court battle may well reveal more about Alden’s DFM management, recently excoriated in The Nation and in the American Prospect. Even LexisNexis’s Law360, which first reported the lawsuit, describes Alden as a “much-maligned ‘vulture fund.'”

Alden’s “milking” of its newspaper properties has been apparent for years. What the lawsuit may reveal is what’s happened to the 20 percent-plus margin profits that Alden continues to methodically wring out of distressed newspapers.The 24-page lawsuit:

In more detail, the suit alleges self-dealing by Heath Freeman, president and co-owner of Alden.

Takeaway: On the surface, of course, this appears to be an obtuse battle between two investors whose company has pursued the most aggressive, and sometimes mean-spirited, evisceration of some once-proud newspapers. They’ve done damage to the papers, but more importantly to their communities and readers. DFM’s business activities have seemed like a legal looting of the public trust. It may be as likely that these two parties will settle their profiteering differences out of the public eye. As one seasoned private equity investor cautions: “Most times, it’s wrath and fury signaling nothing, but every once in a while there is actually self-dealing or fraud of some sort.” For the moment, the lawsuit provides unusual visibility into the nest of secretive vultures.

The latest Steve Brill/Gordon Crovitz startup (which I described in detail last fall) takes an easy-to-understand traffic light approach to combatting the scourge of fake news. Its promised green/yellow/red signals seem like they should be brain-dead simple for even the least brand-aware of news readers to discern fact from fiction.

Now the dynamic Internet duo (who built and sold — twice — their Press+ paywall tech company) have secured the $6 million in funding they wanted. Most notable about the announcemen is the lead funder: Paris-based Publicis Groupe, one of the biggest ad buyers in the world.

Why did Publicis participate? In two words, brand safety. Digital advertisers have grown increasingly leery of finding their brands alongside hateful, deceitful, and incendiary material. A NewsGuard-like system could help ad placers stay away from the dark sides of the web.

But consider one other possible scenario. What if ad-serving platforms — including those of Google and Facebook — incorporated such signaling into their own tech? They could offer brand-safety assurance — and maybe even add a tiny surcharge for it. Of course, such a signaling might also cut off their ad serving business on the no-goodnik “red sites” — but they’re saying they want to be good citizens, right?

“Publicis is a dream lead investor,” Brill says, but keep that thought of platform use in mind as NewsGuard aims to get traction and launch later this year. The startup, of course, craves that standard of digital success: ubiquity. The first step in that is getting a major platform to adopt its rating system, and apply it. That would mean Facebook deploying it on its publisher content and Google on its publisher search and mobile presentation offerings.

That’s the big win: getting both of them to adopt. Unless at least one of those two do, though, it may well fail in its anti-fake news mission. Might Microsoft’s Bing, or Twitter, or LinkedIn, or YouTube be a first adopter? Would it be enough?

With its funding announcement, NewsGuard also announced that the versatile Jim Warren, who just finished a good run with a daily Poynter news industry column, will head the presumably green eye-shaded digital news checking crew. That group could grow to 50, as NewsGuard aims to signalize and write a “nutrition-label” is-this-site trustworthy précis on the top 7,500 or so news sites in the U.S. Eric Effron, last at Reuters, will serve as managing editor.

The redoubtable Warren and artificial intelligence? NewsGuard should be interesting to watch.

Takeaway: NewsGuard could be a simple, elegant solution to both the honest hand-wringing and the overwrought blather about fake news. But we still have to ask the question that NewsGuard won’t answer until it has to: What color is Fox News? Wait for the next NewsGuard announcement. Can it get either Facebook or Google to sign on, or work its way upwards with a next-level player?

Two local-news companies have focused on the large millennial populations in urban centers. Now, with several years under their collective belts, we can report some intriguing numbers.

By far, their number one source of revenue: sponsorship.

“Advertising with Facebook and Google is effective and they’ll continue to gobble up the majority of local advertising dollars,” Ted Williams, who started up Charlotte Agenda three years ago, told me this week. “We don’t sell against them — that’s dumb. We specifically target clients that understand digital brand advertising and want to reach the next generation of Charlotte. This means turning away potential revenue from clients only focused on lead generation or maximizing low-cost impressions.”Williams says Charlotte Agenda pulled in $856,000 in sponsorship revenue in 2017, generating 65 percent of its $1.3 million in revenue. That’s up about 55 percent over 2016, says Williams, who says the Agenda, with “6 FTEs, 2 PTEs, and about 5 core freelancers,” is profitable.

Meanwhile, 21-person-strong Spirited Media — Jim Brady’s three-city (Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Denver) operation — takes in 75 percent of its revenue from a combination of sponsorship and events. Unlike Charlotte Agenda — which focuses on site, social, and newsletter sponsorship — Spirited’s sites still focus on events. (The span of Lab coverage of Spirited here.)

Brady acknowledges a rough patch in 2017, which included layoffs, but says the last four months have restarted the revenue engines, as his sites have better learned how to pull in sponsors. Further, the sites now actively pursue membership — and have connected a newsletter strategy to that conversion well. After revving up that initiative, Brady says, “we’re at just under 600 after five weeks in Denver, three in Pittsburgh, and two in Philly.” Spirited is also beginning to license its self-developed platform, which it calls Bridge, and consult for other startups.

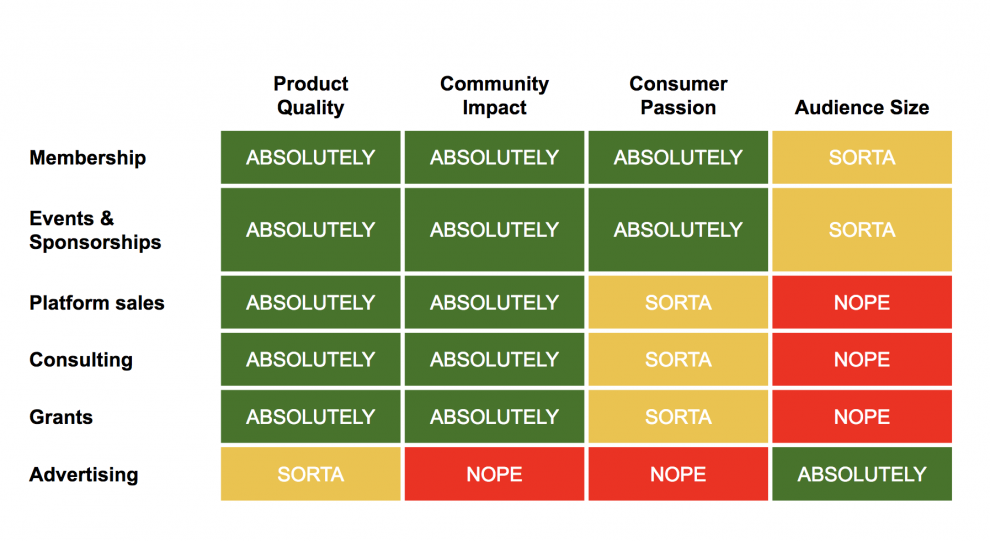

Brady spoke candidly to last week’s Megaconference in San Diego, sharing the travails of a four-year-old startup. One slide sums up a lot of learning, below.

Down the Y-axis are Spirited’s revenue categories, all in some stage of development. On the X-axis, he’s arranged four factors that he’s learned drive — or don’t drive — revenue lines. There’s a lot in this one chart for rising entrepreneurs and those who follow them.

Takeaway: Small can be beautiful. These lively sites, staffed by young journalists, do attract readers, and increasingly loyal ones. Using newsletters and Instagram, they can find audiences that are under-served by existing local media.

Rumors have swept across Advance Publications country, from Portland to Syracuse and in between, of Advance “going paywall.” The Newhouse family’s company made big news six years ago when it chose to throw itself headlong into the digital world, cutting print frequency back to three or four days a week in big and medium-sized cities.

Over the years, it’s stuck to its strategy and that’s brought in little digital reader revenue, other than from e-editions. As digital ad sales have gotten tougher, observers, including me, have suggested that Advance’s strategy and its forsaking of reader revenue was poorly timed.

So is Advance going paywall?

I asked Randy Siegel, CEO of Advance Local. The answer: sort of, slowly, maybe.

“Advance Local is researching a number of options for digital subscription revenue, including recent tests with paid newsletters and high school sports,” he told me. “Due to our success in building highly engaged local audiences, and in light of the evolution in consumer behavior toward paying for high-value digital offerings, we believe now is the right time to explore options to diversify our revenues with various paid digital content strategies.

“We expect this work to take several months of discovery as we leverage learnings from our own experiments and from industry peers. If we decide to test anything, it will be a dynamic meter in a single market but a final decision won’t be made until much later this year.”

Takeaway: Expect a test, and one using the new “dynamic” meters now increasingly embraced by everyone from The Wall Street Journal to smaller titles testing with Piano Media and Mather Consulting. Given recent layoffs at Advance’s Oregonian and buyouts now in process at several other Advance properties, the need for digital reader revenue seems fundamental to any daily newspaper’s business model.The Athletic has turned a lot of heads over the past year. This week came another $20 million in announced venture funding, further indication that it’s going to be a big, serious enterprise — and one aimed competitively at metro newspapers’ sports pages.

Evolution Media, TPG Growth, and Creative Artists Agency have led 18 investors in pouring $30 million in total into CEO Alex Mather’s operation, the no-ad, subscription site (currently $48 a year), plans on expanding to 45 markets across North America from 23. It may double (or more) its staff of 120. The company says it has signed up 25,000 subscribers and attained profitability in a couple of its cities.

There’s lots more to be written about The Athletic and its model, but for now, its innovation tells us so much in what is a bleak time for the journalism business overall.

As a subscriber and analyst, what I find about The Athletic is how unremarkable its model is: Find top reporting and writing talent, pay them fairly, and give them the freedom to communicate with their readers directly, writing short or long.

The Athletic has poached many top talents from metros — and has benefited as national outlets like ESPN and Sports Illustrated have laid off staff. That’s good luck for The Athletic. But its good fortune it’s earned in a simple well-executed product that relies on old-fashioned — but contemporary and deep — journalism.

Takeaway: Jessica Lessin’s The Information has become a darling of new paywall thinking, and it deserves kudos. Yet, The Athletic’s act — with an easily affordable subscription — reminds us that the digital reader revenue game, for the masses, is still in its infancy.

The story of German media giant Axel Springer’s big U.S. push, and the principles behind it, has been well told. Its big move came in late 2015 when it paid about as much for Business Insider as Patrick Soon-Shiong is paying for the L.A.Times, half a billion dollars. Then, two years ago, it bought eMarketer. In total, it’s made about 19 U.S. investments, including Tony Haile’s emerging Scroll, Ben Lerer’s Group Nine, Mic, and Ozy.

Now, Jens Mueffelmann, the CEO of Axel Springer Digital Ventures & President Axel Springer USA, is leaving the company. Mueffelmann, a well-known face in the venture trade, will stay in the U.S. and pursue venture work on his own.

Takeaway: Consider the news just one more sign of consolidation. Even the biggest companies now circle their companies around their largest investments — BI and eMarketer, in Springer’s case — with the case for new newsy startups harder and harder to justify.