Do private hospitals in India perform an unnecessary number of C-section operations in order to make more money? It’s a common worry among Indian families, but until recently there was no official data to back up their concerns.

Then data journalists working at How India Lives, a three-year-old startup whose mission is to make public data more easily accessible, stumbled across a database India’s central health ministry had been maintaining.

The health ministry wasn’t looking at C-sections specifically; it was tracking pregnant women and newborns for a study on how to reduce infant and maternal mortality rates. But when How India Lives journalists dug into the dataset, they found that the numbers supported what many Indians had considered common knowledge: the number of C-sections conducted at private hospitals was almost three times as high as the number conducted at government-run, public facilities. (Private hospitals were also conducting C-sections at three times the country-level percentages recommended by the World Health Organization.)

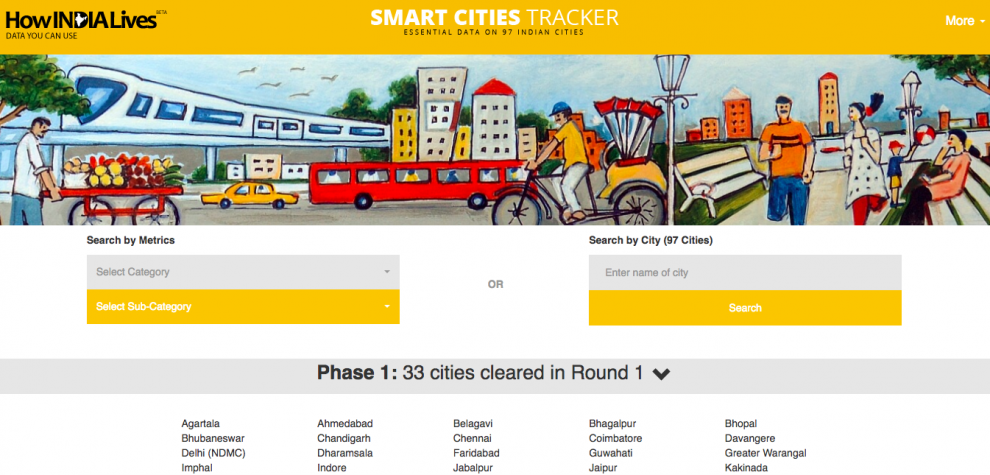

How India Lives wants to be the go-to search portal for publicly available data in India. It also operates as a data consultancy and agency for data-driven news stories that attempt to answer questions in the public interest by transforming difficult-to-obtain and analyze data into something more accessible. In its first year, the company worked with multiple editorial partners to publish its data stories; it’s since signed an exclusive publishing agreement with India’s second-largest financial news daily Mint, which has commissioned and published more than 150 data stories from How India Lives to date.“We want to be enablers for journalists to use public data for storytelling,” John Samuel Raja, How India Lives’ cofounder, said. Raja has worked across several of India’s major financial dailies, including India’s largest business newspaper The Economic Times, for more than 15 years. He worked on the idea for the company at the Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism, where it won a $16,000 grant to kickstart the venture. (That’s been the team’s only grant funding so far.)

How India Lives, founded by five journalists with a range of experience at mainstream Indian news organizations, now has a mix of 11 total full-time and part-time staff — six reporters, two dedicated coders, and three data analysts. On top of data stories for Mint, it’s done research and consulting for 28 clients, including organizations like IDFC Foundation and Ashoka University. The company has been profitable since its first year, and hopes to clear $230,000 in revenue this year. Two-thirds of its revenue now comes from its consulting work.

Indian journalists who want to work on data stories face several major hurdles, including the availability of data in a clean, analyzable format and the skills required to build clear and useful visualizations. Other organizations might have questions that can be answered via publicly available data — what’s the philanthropy situation in India? — but don’t have the capacity to go searching for and processing the data. How India Lives responds to these obstacles.

Raja says that the Indian government actually makes available a good deal of public data, but relatively few people make use of it. How India Lives has been able to, for instance, analyze public data collected by the government’s education department to show a strong correlation between having a functional toilet in schools and school dropout rates among girls. It analyzed roughly 39,000 government job postings for government officials to show just how frequently some government workers transferred jobs.

“Public data is quite hard to come by in India. Even if it is accessible, it is structured in such a manner that it almost becomes impossible to use it effectively,” Saikat Datta, South Asia editor of Asia Times Online and an Indian investigative journalist, told me. “The time and effort needed to structure and analyze the data leads to very poor returns, in terms of readership and insights.”

A lot of other public data is outdated, or can be faulty because of collection errors, Samar Halarnkar, editor of another major data-driven news outlet IndiaSpend.com (and a former Nieman Visiting Fellow), added. And many Indian journalists remain uncomfortable with data journalism, he said: “They do not know how to use data to lend strength to a narrative, or vice versa.”

While India’s made progress in making public data available through portals like data.gov.in and a data-sharing policy, the quality and comprehensiveness of what’s available continues to hamper data journalism. Often government departments upload scanned copies of the data as JPEGs instead of making the spreadsheet available online.

Census data, which used to cost a fee to download, is now free, and How India Lives has incorporated the information into the simple search portals on its site. But other sources like Survey of India — which has a monopoly over mapping data in India — and the Indian Meteorological Department are still paid. Indian authorities also used to put out detailed export and import data on daily basis, but stopped abruptly without notice in December 2016: Companies, many in the manufacturing sector, objected to the sharing of these figures, argued that it revealed competitive information.

Besides How India Lives, several other established organizations such as IndiaStat, Social Cops and Gramener also work in the data analysis and visualization space. How India Lives pitches itself as the only one working at the intersection of three circles — journalism, technology, and public data.

How India Lives is hoping to roll out more advanced data products in the coming years, with a continued focus on creating customizable services to surface new datasets to present to paying clients in a searchable, comparable, and visualizable format, How India Lives cofounder Avinash Singh told me. Its consulting business, Raja said, has helped his team understand what types of questions people want to answer with data, and in what specific formats they want to consume that information.

How India Lives currently offers a beta search engine for public data covering only census information, with 2,300 categories of data on 715,00 geographical locations across India. The company is now building out a paid-for search product, which will offer 18,000 new data categories for all these locations, with new datasets, such as the Socio-Economic Caste census, added. Access to some of this will remain free; the team is hoping to make the expanded search features available around the end of this month. It also wants to make the process of adding new datasets easier, and build out avenues for other people to submit datasets themselves, according to Singh.

“As new technology solutions come, journalists use them,” Singh said. “But our solution can be used not only by journalists but also by organizations for their own decision-making.”