Penelope Abernathy’s latest report on news deserts is damning.

About 1,300 U.S. communities have completely lost news coverage. More than one in five newspapers have closed over the past 15 years. And many of the 7,100 surviving newspapers have faded into “ghost papers” that are essentially advertising supplements.

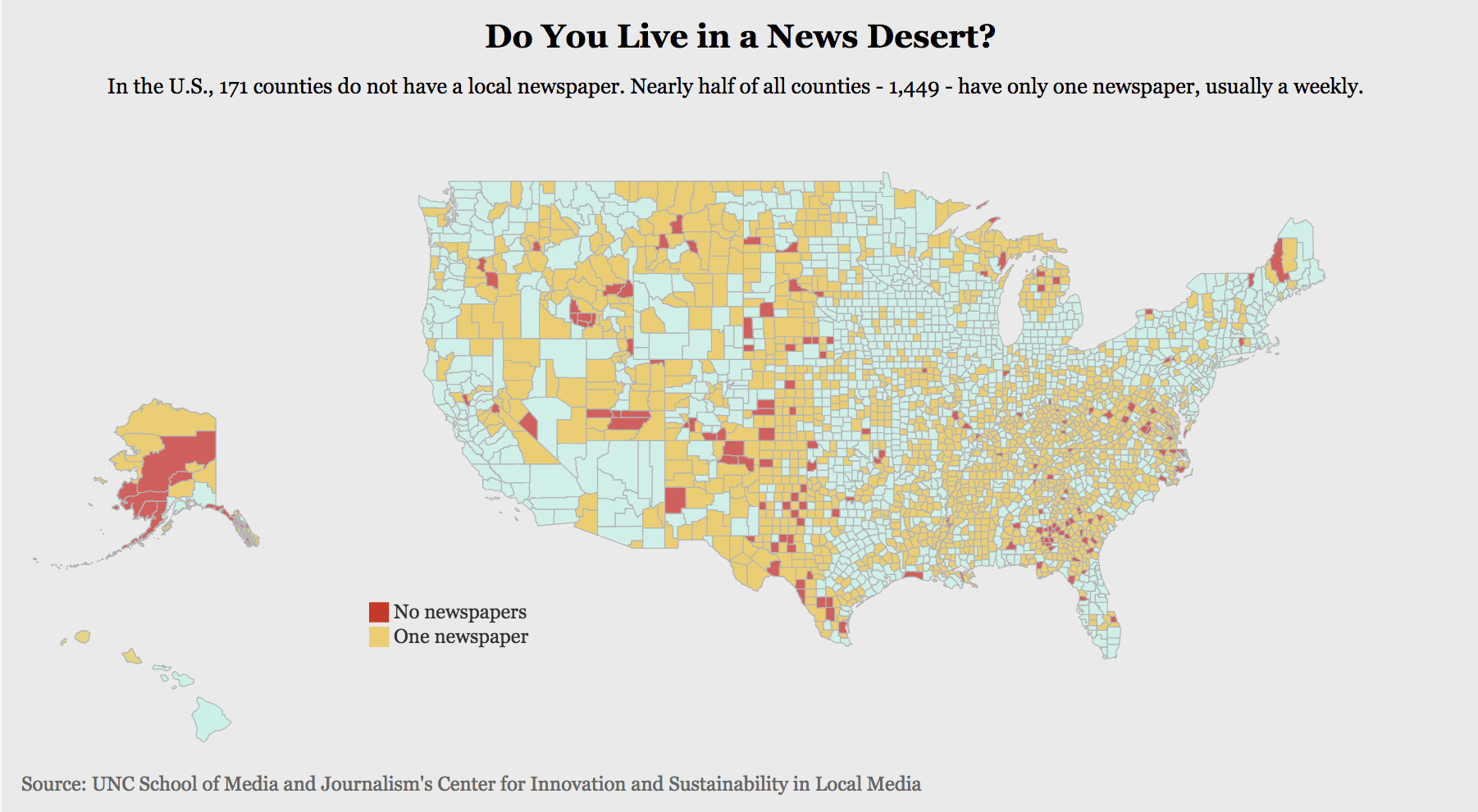

Half of the 3,143 counties in the U.S. now only have one remaining newspaper — and it’s usually a small weekly.

Some shuttered weekly papers were absorbed into larger daily newspapers whose priorities had shifted (looking at you, Jeff Bezos) or haunted the doorsteps of every resident in town as the advertising-laden ghost newspaper.

But the word “weekly” means more than just “published three times or less a week,” as Abernathy defines it in this report. The weeklies are the integral steps of the news industry food chain that feeds into the larger dailies whose layoffs we bemoan, like at the Denver Post and the New York Daily News. And their audience hasn’t gone away:

The decline in daily circulation was driven by the largest dailies shedding existing readers….In contrast, the decline in weekly readership resulted primarily from the shuttering of 1,700 papers. The average circulation of the country’s surviving 5,829 weeklies is 8,000, roughly the same as it was in 2004.

The numbers in the media industry are dire, but weekly papers don’t necessarily have to be casualties. I spoke with Abernathy, UNC’s Knight chair in journalism and digital media economics professor, about the role the weeklies play, how business owners view weeklies in their portfolios, and the rise of the “ghost newspapers.” Read the full report (and dive into the multiple interactive maps) here. Our interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Regional papers gave you the broad picture, but they picked up what was on the ground from the weeklies. Most of the papers that were under 15,000 [circulation] have historically been weeklies. Those newspapers built a community and they also educated you about what was going on in the community. They did that in three ways:

If you think about what has really fed democracy at the grassroots level, it has been the thousands upon thousands of communities in this very large country. It has been the weeklies or non-dailies binding us together at the grassroots level that feeds into the larger ecosystem which feeds into the larger dailies and national and international dailies.

Post-2009, it has become very hard for weeklies to go it alone. We noted in the study that the number of independently owned weeklies or non-dailies has decreased from roughly half to less than a third. A number of those weeklies that could just not do it alone went out of business. Or they got bought and were subsumed into other dailies. There’ve been two paths for them: If they couldn’t make it on the local retail business, they either merged with the larger daily or just went out of business.

For the first instance, The Chapel Hill News was bought by the [Raleigh] News & Observer and over a period of 20 years it became what we call a ghost newspaper. It went from being a standalone newspaper to being a zoned edition to most recently being an advertising supplement. It doesn’t cover the kind of stuff that informs you as a resident of a community or help you make decisions that inform your life or the life of your children. It focuses primarily on lifestyle, dining, and entertainment. We counted roughly 600 papers that had become ghost papers by that route. Or, if you couldn’t find somebody to buy you, you went out of business.

The surviving independents have had to be very creative about where they go for additional revenue. That means they go outside their market, they partner with other media organizations, they come up with something that defies the local gravity. They say “what do our businesses need to succeed” — they offer marketing services. And they project out and say “I’m going to build a business plan that’s five years out and go backwards…I may have to stop doing some things but I’m going to do things that I think will make a difference.” They invest in their human capital which is both their news operations and their sales and marketing operations.

A similar thing happened to News Corp. when it purchased the Wall Street Journal. The Wall Street Journal, like The Washington Post, had a chain of small dailies and weeklies that were mostly up in the New England area but spread up and down the East Coast. The main reason for buying something was to get the main, large daily. You come in and say, “Is this really in my strategic wheelhouse?” You either sell them, as News Corp did with the Ottaway chain, or, if you’re Jeff Bezos you make the decision to shut them down. You were buying the daily paper and they came along at a pretty inexpensive price.

To them, it’s about not just streamlining the priorities but saying, “Here’s where I want my strategic priorities to be.” Jeff Bezos was very clear that he wanted to put The Washington Post on a national level. That means investing in political coverage and the sorts of things that will resonate throughout the country. Invariably, that meant he walked away from the suburbs of Washington, where The Washington Post company had always made a strong commitment.

So most of those ‘new weeklies’ were actually shoppers.

Advertisers are very loyal to the papers, but acknowledge that they have to go where the readers are. As long as the weeklies can keep figuring out what the advertisers need and give it to them — marketing they’ve never done before, not just print advertising — I think really savvy, farsighted publishers have a good chance to make a successful transition. It’s not going to be easy, because the business model that sustained weeklies for almost 200 years has disintegrated. They have to come up with a business model that serves the community, invest in their human capital — their news-gathering operation as well as their sales and marketing operation — and keep a longterm perspective, by asking what they need to survive and be in a position to start thriving in five years. Those who work backwards by prioritizing those projects and initiatives that are going to get them there are going to be in a much better place. They already have a groundswell of loyalty and a real foundation on which to build in many of these communities.

It is critical to our democracy that we come up with business models for whatever is the 21st century version of newspapers. That’s regardless of whether it’s distributed digitally, broadcast, or in print. I do think some version of print will survive. There are several instances of digital-only enterprises evolving into printing weekly or monthly. The print serves a very different function from the digital function — the digital tends to be what’s happening now, the print is more of a weekly magazine for the community.

Less than five percent of philanthropic funding over the last few years has gone to state and local news sites. It’s going to take a very concerted effort that involves community activists agitating for it, working with philanthropic organizations, even working with local and state government to figure out what the solution for this is.

What’s needed now is the realization of where we have news deserts, what we can do in the short term to turn that around, and what we can do long term to develop for profit business models. Unless we have a for-profit business model for weeklies, we’re not going to have a vibrant news ecosystem.