Editor’s note: Jeff Israely, a former Time magazine foreign correspondent in Europe, is cofounder of a news company called Worldcrunch in Paris. For the past nine (!) years, he’s been describing and commenting on his company’s growth process here at Nieman Lab. Read all his past installments here.

If you ask my political-junkie son, the pinnacle of my professional career was Michael Wolff (15 years my senior) accusing me on Twitter of “sound(ing) so old fart-ish.” It was a description any teenaged son could agree with — not to mention the sheer glory of having your father publicly insulted by the guy who’d screwed Steve Bannon!

you sound so old fart-ish. RT @jeffisraely: @MichaelWolffNYC a master "aggregator" out of a job…look hard , you can find his links too!

— Michael Wolff (@MichaelWolffNYC) May 19, 2010

I’d dug up the old exchange for a laugh when Wolff’s Fire and Fury was all the rage, but it dates way back to 2010, when I’d taken a passing Twitter slap at Wolff’s website Newser for not respecting the copyright holders of the articles it was systematically aggregating. At the time, we were preparing to launch our own digital news operation built around distributing top international journalism translated into English — so the Newsers and Huffington Posts of that world were the obvious opposite of our declared business model of monetizing full-length, copyright-cleared journalism.

In retrospect, my curmudgeonliness aside, the jury is still out on the economic viability of either approach. Indeed, after last week’s layoffs at BuzzFeed and HuffPost, some are asking if there is any sustainable-scalable model for digital news. (More on that below.)

Truth is, my four-tweet exchange with Wolff was the closest I’ve ever gotten to a bonafide battle in nearly 10 years on Twitter. Despite all its shortcomings and time-sucking, Twitter instead has always been nothing more or less than an efficient way for me to follow the news — and the people at work in the business of news.

Another news industry person I began to follow back then was Rafat Ali, who’d recently sold his company paidContent to the The Guardian. In the years since, I’ve watched from a distance as Ali builds his current company, travel industry media Skift, to a 60-strong staff with an impressive mix of welcome-to-the-digital-revolution swagger and the razor-focused pragmatism of a mid-sized business owner.Worldcrunch, we might say, is everything and nothing like Skift. Not yet quite a mid-sized business, we are continuing our pivot from that initial news syndication model to a mixed approach that includes digital editorial services for clients, distribution, and a recent focus on photojournalism. We follow our passions, but we’re as pragmatic as Skift, and have finally (and proudly!) gotten our balance sheets to break even. But while both enterprises aim for a global audience and opt for depth and quality over chasing clicks, Skift has a more direct path to reach its market for one big reason: It’s B2B and topic specific. We are (shhhh) generalists.

Here’s Ali last week: “Media is a simple business: You pick a sector, cover the shit out of it, get an audience, you either sell them, which is advertising, or you sell to them, which is subscriptions or paid services, that’s it. There’s no other way to do media.”

No other way? That’s probably a bit of that swagger — and it’s clear he’s speaking about for-profit endeavors. Still, his words hold extra weight in the midst of the recoiling of some of digital media’s top general news operations. So we’ll ask again: Is there really no sustainable form for digital news other than B2B vertical media?

As a Paris-based but anglophone publisher, our business has grown by a kind of reverse engineering of the B2B model. We work across a range of topics, capitalizing on our English-first edge on the French (and European) market for both our paid services and modest worldwide audience. We’ve also tapped into partnerships and foundation support, while pursuing at least two distinct revenue opportunities linked to photography. Sure, forging ahead without a specialization makes both our services and audience more diffuse. It requires us to seek ways to segment our coverage and audiences, while retaining the ongoing objective to make it function as a coherent whole.

But beyond product and model lie the twin questions of a media venture: pace and scale. The digital startup gospel often includes the pursuit of venture capital and/or a commitment to either make it big or fail as fast as possible. And this brings us back to the big industry news from last week. Rafat Ali has long extolled the virtues of keeping outside investment as limited as possible, warning about the downsides of the chase-the-eyeballs, venture-backed digital outlets that we’ve seen play out over the past 18 months, culminating with the recent avalanche of layoffs.

Don’t blame investors for investing, that is their job. The *only* job founders have, meanwhile, is to build a sustainable, long term business. “High growth at all costs” is NOT a necessary condition to it, merely a causation founders build themselves in their minds.

— Rafat Ali, Media Operator (@rafat) November 17, 2017

We made sure to never take millions from Disney or Murdoch. (Okay, so they never offered!) Still, it does feel like a better place to be right now for the founders to have ultimate control. You’ll often hear the term “runway” to talk about the time needed to build momentum to allow a business to finally…take off. Internet founders know that the lenghth of runway is calculated by a rather simple formula: cash × control, where a higher rate of self-generated cash increases the rate of control.

Watching the bad news of BuzzFeed and HuffPost layoffs spread on Twitter brought many of us with roots in the legacy media back to similar moments in the past (and present). Bitterness. Loss. Bewilderment. A smidge of self-righteousness, as we wonder about the state of our democracy when straight-shooting professionals who simply want to cover their beats, expose injustice, and publish quizzes are suddenly cut loose.For old and new reasons, these are all questions worth asking — and anyone tossed into joblessness deserves basic empathy. Still, those pursuing a career in news are now almost required to also ask questions about the business side of the equation, and think hard about where our place can be in this industry that, yes, is consolidating, but also changing every day.

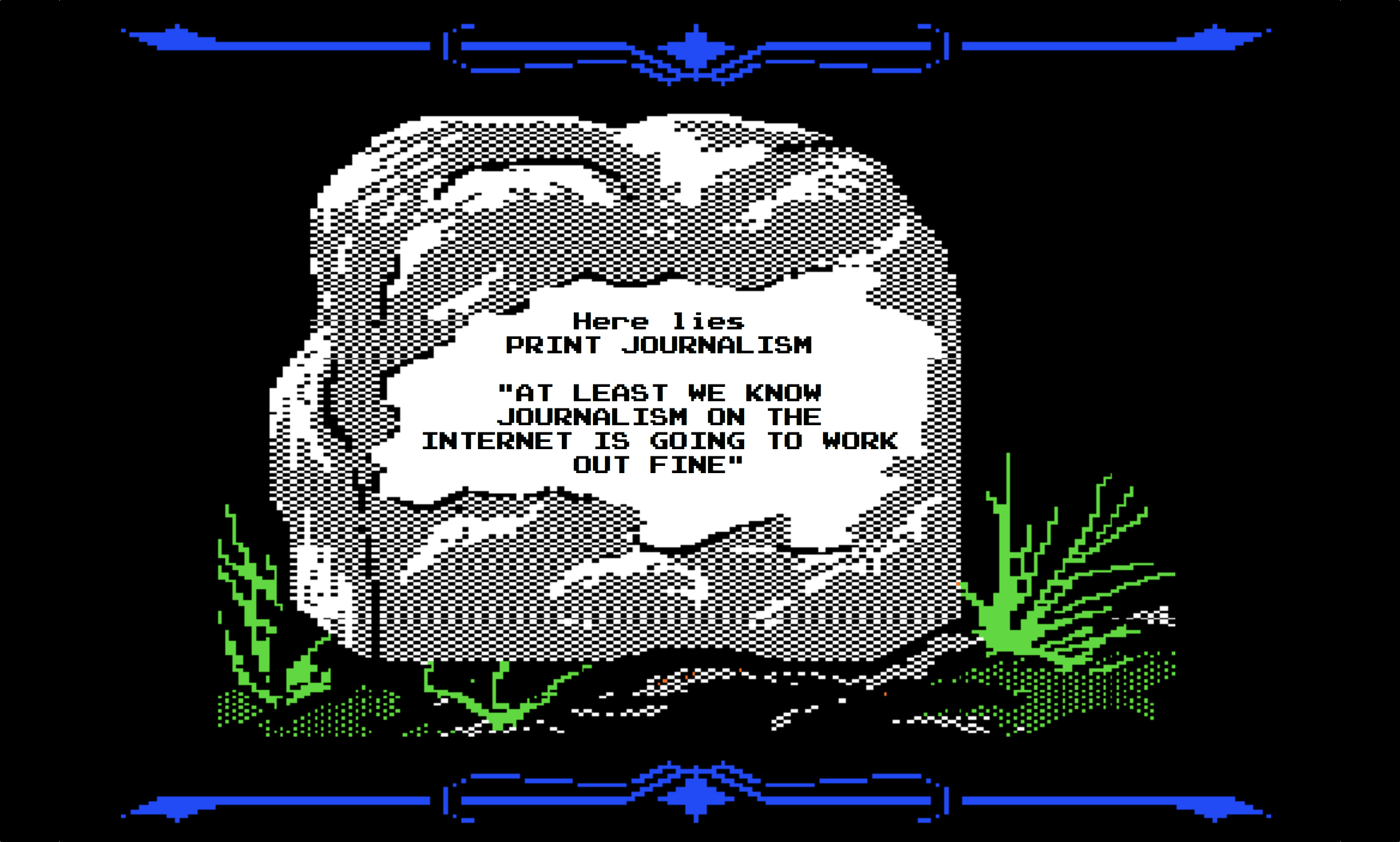

One of the mantras accompanying this round of layoffs is to blame it all on the “duopoly” of Google and Facebook for gobbling up all the ad revenue. No one can deny that something is fundamentally broken in the model for digital news — and much more of what is happening online. But breaking up the duopoly wouldn’t solve the deeper questions about how to make money delivering information when it’s available instantly, anywhere, and theoretically at zero cost. In 2009, it was: The internet is killing (print) journalism. In 2019, it’s: The internet is killing (internet) journalism. The truth is that journalism isn’t about to die — but neither is the internet. More than the next big thing, we should all be looking for a longer runway.