Welcome to Hot Pod, a newsletter about podcasts. This is issue 194, published February 5, 2019.

Happy Lunar New Year, everyone! Okay, so, obviously I’m going to go long on the Gimlet–Spotify deal this week, but we need to start with some other stories first, because plans were made.

A quick exclusive: Vox Media has added Switched On Pop, a popular independent music podcast by Charlie Harding and Nate Sloan, to its podcast network. The show will officially relaunch next month as Vox’s first music-centered podcast and will publish on a weekly basis. This is Vox Media’s first external podcast signing, though Harding and Sloan will retain ownership over the show.

Why file organization matters [by Caroline Crampton]. Preserve This Podcast exists to help podcasters protect their work against digital decay. Funded by an $142,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation, it started work in February 2018; it’s tackling a a problem they argue will hit podcasts other than other forms of mass media because cultural heritage institutions aren’t as yet focused on preserving them.

A big part of the project is improving awareness of the problem, but they’re also collecting data about how people currently create, back up, and preserve their podcasting work to get a snapshot of the status quo. To this end, they’ve conducted a survey, and I’m going to digest some findings from that work for you now.

To start, a brief note about terminology. There’s a difference between “backing up” your audio work (saving files in multiple locations to guard against a laptop failing, for instance) and properly “archiving” it. I’ll let PTP team member Molly Schwartz of the Metropolitan New York Library Council explain it.

“There’s a few things that go into it,” she told me on the phone last week. “One is having file organization in some kind of setup so that if someone else is looking at it, they would know what is where…Also, have all the necessary metadata and forms and other files with your podcast collection. Release forms, photos that you’re using, transcripts. Keeping those in a collection with the audio files is something I would consider part of archiving a podcast.” Another good archiving practice: preserving raw tape and draft cuts in uncompressed formats along with any final versions.

That said, PTP’s survey revealed some interesting insights into podcasters’ tech habits. There were 556 respondents, 72 percent of them in the U.S. Around a third produce podcasts full time and two-thirds make audio independently. With this last stat in mind, one of the biggest trends to emerge was the gap in digital preservation practices between indie producers and those working for an institution. Of the 27 percent who say the back up uncompressed versions of all of their files — what Schwartz calls “preservation completists” — 68 percent of them work for institutions.

That’s not surprising, since those working inside a media company or podcast network are more likely to have had training or guidance on how to organize their files. Within even that cohort, though, there was still a substantial knowledge deficit, Schwartz said.

“What was interesting to me was even though people who worked for institutions were more likely to have stronger preservation practices, they didn’t necessarily know what their institution’s preservation policies were,” she said. “And that’s actually a big outcome of this: It makes us aware that this should be a wider conversation within podcasting networks and public radio stations.” 28 percent of respondents said they didn’t know their institutions’ procedures, and 11 percent said their organization had no system in place.

Another trend concerned the Internet Archive: Podcasters who submitted their work for preservation there were more likely to be clued up and to feel strongly about keeping their work safe. “They were very likely to be preservation completionists and they were significantly more likely to actually back up uncompressed versions of all their files,” she said. “They’re more likely to have what I would consider their own self-made systems such as a hard drive or Apple Time Machine as opposed to relying just on cloud storage.”

The survey also threw up some intel about what PTP are calling the “precarious outliers,” the 7 percent of respondents who said that they don’t back up their files at all. Around half of those also don’t rename or organize their files and have little or no knowledge of institutional policies. Although the small size of this group is relatively positive, PTP hopes it can help these people keep their files safe.

PTP has its own podcast launching on March 21; the team is also adding resources to their website, and through 2019 they will be running in-person workshops (the first one is in New York on 22 March, keep checking the website for more dates and locations). At these events, Schwartz says, podcasters can bring all of their hard drives and equipment, and get help to put a preservation plan in place on the spot.

There’s a bigger purpose behind all of this, Schwartz says. Podcasting is a relatively accessible medium, attracting creators who wouldn’t be able to air work through traditional channels. If individuals can preserve that work for the future, it’s a way to save a record of that diversity. “Podcasting has been such an open medium, and everyone has stories to share and this space to put them, and we think it’s equally valuable,” she says. “I hate the idea that just because people aren’t aware of certain file management practices that they don’t make it into archives or in history books.”

Find out more about the project at preservethispodcast.org and keep an eye out for the podcast of the same name, which drops next month.

Gimlet–Spotify, or the end (of an era). Quiet weekend, huh? In case you missed it, Spotify is reported to be in “advanced talks” to acquire Gimlet Media. Recode and The Wall Street Journal both had the story late Friday. And let me tell ya, my inbox saw more over the past 72 hours or so than it has in a long time.

If you didn’t catch the emergency newsletter I sent out on Friday, here are the beats:

In Friday’s emergency Hot Pod, I noted that there was a certain inevitability to Gimlet’s exit. By that I meant that, having taken substantial amounts of venture capital, the company had to operate under the assumption that its investors would want an exit in some form or another. Going public was probably never realistic, given that content-oriented companies aren’t exactly the most listable entities in public markets, and founders Blumberg and Lieber generally opted to eschew any kind of technology play fairly early on (as documented in StartUp’s first season).

One could argue that Gimlet set itself down this road once it committed to a growth plan that required what must be a blinding burn rate. The company’s headcount now numbers around 120 people, and it committed to a 10-year lease in downtown Brooklyn in 2017, where it proceeded to invest heavily in building out studio infrastructure.

All this, it should be noted, came off the strength of a three-pronged revenue stream: podcast advertising sold on its 24 owned-and-operated shows; branded podcast campaign revenues through Gimlet Creative; and IP-slingin’ through Gimlet Pictures (which I’m guessing doesn’t produce that much upfront money and may well be a comparatively unreliable revenue stream at the moment, but it’s growing nonetheless). Gimlet doesn’t make its revenues public, but there are enough clues scattered about. We know that they made at least $7 million in 2016, back when they were more transparent about its inner workings. In mid-2017, a Recode piece reported that the company was on track to bring in $15 million that year. (That’s the number, by the way, that The Ringer hit in 2018.)We can probably assume that its revenue levels have grown since. Maybe Gimlet had figured out a growth rate that would justify its burn, to the point that, in another universe, they could have felt confident about raising another round. Or maybe they didn’t. In any case, they’re selling, and here we are.

In Spotify, Gimlet has found an attractive suitor. The Swedish music streaming platform, which has been itching to do something with podcasting for a while, isn’t just any potential buyer of a podcast company. Indeed, it’s a particularly sexy suitor that would validate the brand that Gimlet has labored so hard to build and whose disruption narrative vibes with the worldview of Gimlet’s tech-centric investors. (A thought experiment: How long is the list of possible suitors who would make an acquisition still feel like an actual achievement?)

Gimlet’s exit might also be well-timed, given the probability of future turbulence. As I brought up last week, some smart folks argue that there’s a good chance of a recession in the coming years. That would bring significant uncertainty to podcast-land as we know it. Such an event would impose considerable pressure on podcast advertising rates, challenge the optimism and confidence around the industry, and truly force the question on whether there’s a podcast bubble. The opportunity to cash out now feels like an understandable choice.

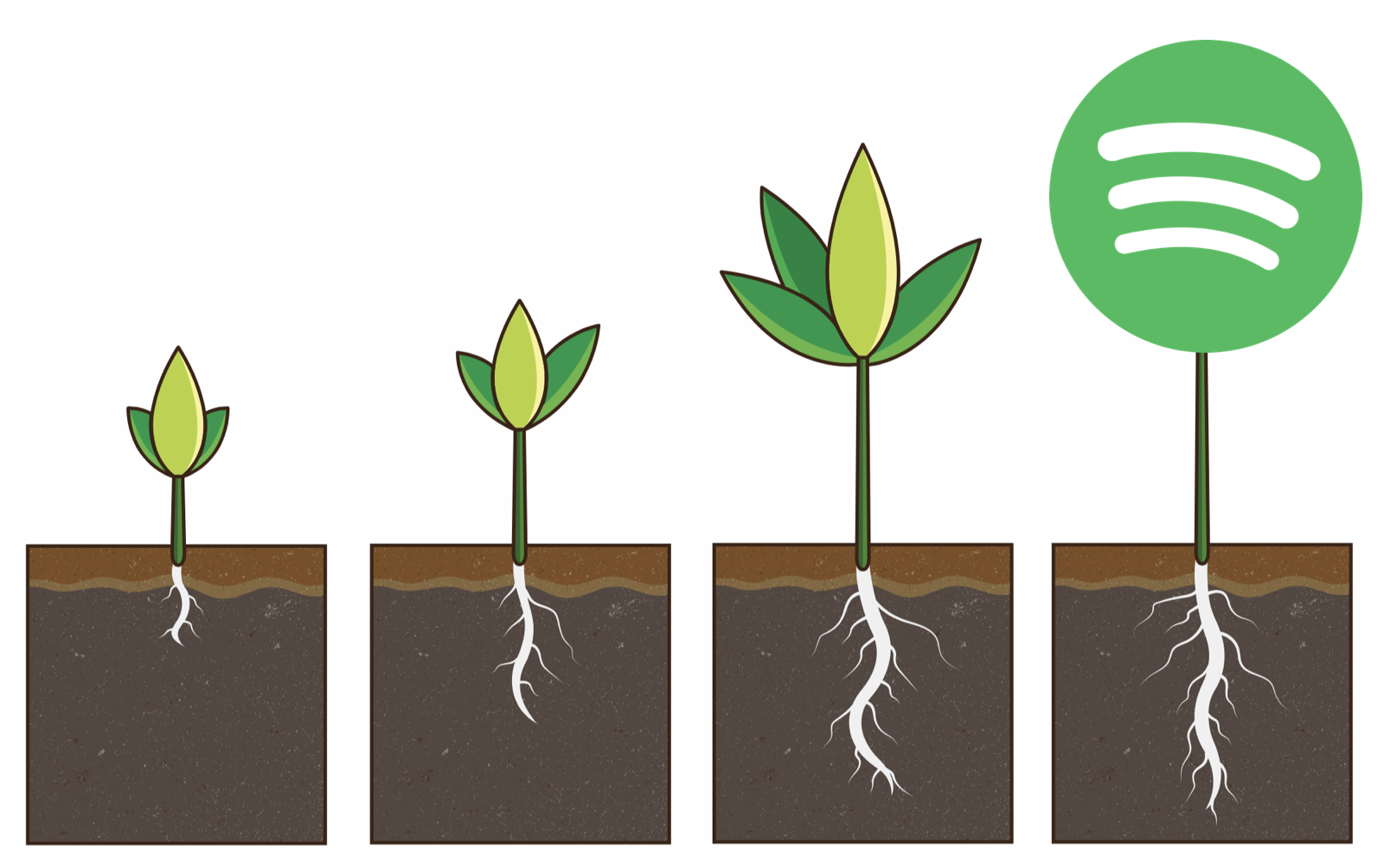

But to quickly recap: Spotify is looking to diversify away from purely focusing on music, where it’s been long locked into bruising rivalries with other streaming platforms (Pandora, Apple Music) and traditional music industry Powers That Be (labels). Podcasts, or talk content more broadly, offers the Swedish tech giant two things: first, a completely new growth channel for investors to get excited about, and second, the opportunity to differentiate its product, deepen its value to the user, and increase the friction of shifting away to another service. (Until competing services ramp up their own respective podcast plays, of course.)

So I wasn’t particularly surprised to hear that Spotify was acquiring Gimlet. First of all, there had been rumors floating around for a while. But there’s also an apparent superficial logic behind it: Gimlet would give Spotify a buzzy portfolio of shows with which the platform can focus attention on and build a narrative around its podcast offerings.

What did surprise me, though, was the $230 million price tag, which was significantly higher than I was expecting. I’d expected a sale around the $70–$100 million range, if only because of Recode’s reporting on the company’s $70 million valuation after its most recent fundraise. Maybe I’m just a naive small business owner who knows nothing about scale or corporate development, but holy shit does $230 million feel like a stretch. Especially when contextualized against iHeartMedia’s $55 million acquisition of Stuff Media, a pure podcast content company, last fall. And your suspicion lies somewhere along the lines of differences in infrastructure, a data point to note: Stuff Media had around 50 employees powering production slate of around 25 shows at the time of acquisition; as mentioned previously, Gimlet has over 100 staffers powering 24 shows.

Which prompts the question: What, exactly, is the specific value that Spotify sees in picking up Gimlet? (An alternative theory is, of course, a simple bidding war. But I haven’t picked up any signs of such a thing, and until we see reliable reporting on the matter, let’s proceed with the assumption of Spotify as the sole suitor.)

So the major assumption I’ve been seeing around this deal is that in Gimlet, Spotify is primarily getting a show portfolio to use as the cornerstone of their “original podcast programming,” with which they could push more of its users towards consuming podcasts on its platform. That push may or may not take the form of Gimlet’s shows becoming Spotify exclusives, but I’m pretty comfortable betting it will.

But I also think Gimlet Creative, the company’s advertising division, is another key piece to appraise here. Consider that Spotify’s core competency isn’t content, but distribution, engagement, and monetization — and that monetization, in particular, is both a podcast problem a good deal of people are fixated on and the one that established media platforms (like Spotify, but also Pandora) fancy themselves well-positioned to solve with their existing assets.

We know that Spotify has been tinkering with podcast monetization; a recent press push noted that the company was experimenting with selling ads on its own original podcasts and that it’s currently exploring the possibility of building out its own ad-insertion tech. And I continue to be convinced that all of this is going to link back to, or draw lessons from, Spotify’s adventures in building direct relationships with musicians — first by striking deals with independent artists and then by rolling out a feature that allows artists to upload music directly and automatically receive royalty payouts. In other words, they’ve been trying to become the monetization layer for musicians straight-up. I imagine they would want to do the same for podcasts.

But of course, podcast advertising is a completely different animal from digital audio advertising as they would know it. (For now, anyway.) Which brings me to my tinfoil-hat theory: One possible future sees the Gimlet Creative team being diverted to focus on developing new-age advertising experiences for Spotify to inject into its original programs and to supply its future podcast monetization tools.

To put it another way, instead of seeing Spotify picking up one end-to-end podcast company, you could also perhaps see it as picking two different (albeit conjoined) assets that can each be applied to different aspects of its business: a publisher and a creative agency.

And what an agency. One can debate whether Gimlet is a category leader in original podcast content — and it’s a debate worth having, competition’s mad fierce — but the way I see it, Gimlet Creative is the company’s most notable creation and quite far ahead of its peer group. This is a creative agency that has developed relationships with, built advertising experiences for (both branded podcasts and in-episode spots), and extracted a ton of money from an array of attractive advertisers, including Ford, Gatorade, Virgin Atlantic, MasterCard, Google, Microsoft, eBay, and Reebok. I imagine that all makes for a pretty attractive asset to somebody. (Not unrelated: Spotify itself has been experimenting with branded podcast production.)

Or maybe it’s all not that complicated. Maybe it really is the simplest version of the situation: a big entity acquires a smaller entity, provides it with resources and support but generally leaves it alone, and reaps whatever benefits that can be generated. Disney–Pixar, essentially.

Maybe. But I never really liked Occam or his razor anyway.

Miscellaneous notes:

The next few months will prove to be interesting, with an array of podcast companies perhaps seeing it as a strong opportunity to cash out. (I’d keep an eye on other venture capital-backed content companies, if I were you.) And given the high $230 million watermark that was just set, those companies could be emboldened to ask for high prices. What I can’t tell, though, is the actual extent to which it’s a seller’s market. On the one hand, FOMO is a powerful force. On the other, as established earlier, the future is more uncertain than it ever was, and it’s quite possible both sides of the table will know it.

Something to consider, though: Unless I’m overlooking some obscure part of its history, Spotify hasn’t governed a big editorial staff before. (They have, however, governed a small staff: that of Dissect, the music podcast it acquired last year.) That could lead to complications. Anyway, keep an eye on how that shakes out. In any case, I’m crossing my fingers that Gimlet and its new Swedish overlords will do good by its producer workforce, and I hope that everybody gets to keep doing what they signed up to do. Unless, of course, they came in for the money, in which case, good for you.

Make no mistake: Should the acquisition close, this deal would be an unambiguously important moment in the young history of podcasting, even if it doesn’t work out. Gimlet-Spotify would be podcasting’s first true blockbuster acquisition, a potential major turning point for the ecosystem (for better or worse), and the beginning of something…else. But as the poets of Semisonic once observed, every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end. In this case, this is the end of an era, the one that was kicked off in 2014 with the Serial Boom. I’ll miss it.

In the February 6, 2018 issue, New York Public Radio was three months into its organizational culture crisis, RadioPublic launched its Paid Listens program, Gimlet (remember them?) formed Gimlet Pictures (awww), and Pandora was reorganizing its business, implementing cost-saving measures to fund new bets on ad tech…and non-music content.