Welcome to Hot Pod, a newsletter about podcasts. This is issue 205, published April 23, 2019.

Gimlet Media has officially recognized its union. The union’s organizing committee first signaled the development over Twitter on Friday. In a statement sent over to me, the committee said: “It’s been a very long road, but we’re officially a recognized union now! Twice now, our membership has affirmed that we want to organize with Writers Guild of America, East to win protections and build a stronger company. Gimlet is now legally bound to recognize us!”Today on RiseUp… we reaffirmed our support for unionizing by voting Union Yes! We now have a recognized union

Thank you so much to all of our listeners, #1u and @WGAEast siblings who supported us during our campaign – solidarity matters. #GiveMeAStrongGimlet pic.twitter.com/dGDxDxOQkQ

— Gimlet Union (@GimletUnion) April 20, 2019

Next up: the bargaining process, which, as I noted in my column on the matter, can take a while.

Luminary, launch, and licensing. Luminary, the much-talked-about paid audio content app that’s raised $100 million in venture funding, officially launched this morning, rolling out its iOS and Android apps in the United States, Canada, the U.K., and Australia. The company kicked off public life with a Medium post presenting its theory of the case, or at least a version of it.

If you’ve been reading Hot Pod over the past few weeks, you probably know most of the details. The company is premised primarily on an originals- and exclusives-driven business model. Its long game is built on the hope that customers will pay $8 a month to access its roster of podcast-style programming. It’s not the first to try something like this, but it’s distinct on three fronts:

— First, Luminary is actively pursuing the podcast community as we know it.

— Second, it’s the first major attempt at a subscription podcast-style audio content service that isn’t derived from a preexisting business.

— And third, it’s raised that aforementioned $100 million, and thus is motivated in accordance with venture capital expectations.

But here’s something new, courtesy of Ashley Carman over at The Verge:

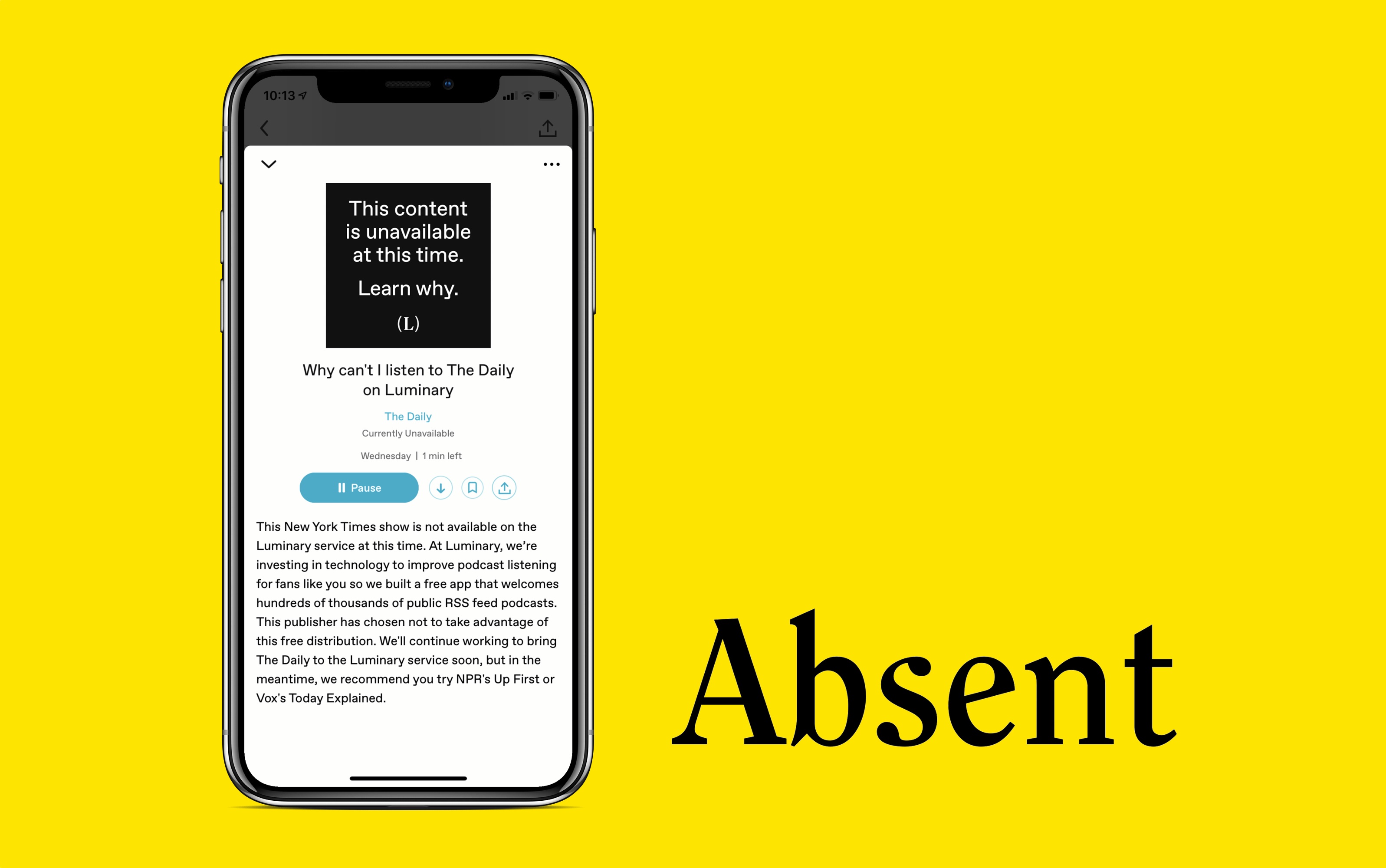

When it rolls out to the public on iOS, Android, and the web, Luminary’s podcast app will be missing some of the industry’s biggest shows, including The New York Times’ The Daily and Gimlet Media shows like Reply All and Homecoming. Shows by Anchor’s network of smaller creators won’t be on the app, nor will series from Parcast, both of which are owned by Spotify.

By withholding their shows, the Times and Spotify are setting Luminary up to fail — or at least struggle to get off on the right foot with users. It certainly seems like the first shot fired in the inevitable premium podcast war and could destabilize one of the first buzzy, well-funded entrants before it can make a dent in the industry. The decisions that happen now will reshape the way podcasts are distributed in the future.

So, this is obviously quite a

Let’s start from the top. If you browse through the app, you’ll notice the experience feels…well, rather familiar. In fact, Luminary is pretty much a straightforward podcast app that supplies users with a free tier of podcasts from the open ecosystem — except that it also comes interspersed with a layer of exclusive content, marked by the Luminary logo, that users would need to pay for. In that introductory Medium post, the company presents itself as both things equally, a free app and an exclusives-driven subscription app, with the argument being that the latter funds the former. But the component with the business model is probably always going to be the one that matters more to the company, and so you can read a utilitarian logic into the design here: The free stuff is what gets people into the app in the first place, after which they’ll hopefully encounter the exclusives and tumble down the conversion funnel into paid usership.

Now about that free tier: Luminary appears to populate its free section by pulling podcasts that are openly distributed over public feeds. Historically speaking, this isn’t an irregular practice. In fact, many third-party podcast apps do this, primarily by mirroring the Apple Podcast directory. More often than not, though, this methodology doesn’t trigger conversations or processes around licensing — i.e., the legal framework that establishes how an app can make money off content it does not own, and so on — chiefly because many of those third-party apps generally don’t command much meaningful market share. (“We often look the other way” is how I’ve heard bigger publishers describe their stances to this.)

Things are a little different these days. As more platforms with big potential podcast listener bases (Spotify, TuneIn, Pandora, and so on) move into the space, there’s increasing precedent for those platforms to actively and preemptively establish formal relationships with various major podcast publishers, often in the shape of signed agreements, so that all parties are super clear on how both sides can make money and not interfere with each others’ business models.

Poking around on this story yesterday, the issue of licensing came up as a major talking point several times. A source close to the matter told me that Spotify’s decision was rooted in the fact that Luminary had only reached out with a licensing agreement at the last minute, and that Spotify’s various podcast divisions weren’t preemptively told their shows were going to be on the platform. Luminary only approached Anchor with an agreement last Thursday, four days before the app launch, while they had not approached Gimlet at all. I was also told there was a very high likelihood that Spotify and Luminary could have worked out an agreement by the app launch, if only the latter pursued an appropriate process.

Luminary denies all this. “That’s inaccurate,” a spokesperson said. “Spotify and Anchor know the facts including Luminary’s constructive stance towards ad-based podcasting and fair play.”

So what exactly are we looking at here? One probable interpretation: Luminary, a deeply venture-backed subscription-first business that largely takes the form of a conventional third-party podcast app, misread how they would be perceived in the industry (as a potentially big platform that needs to engage in licensing agreements, and not a scrappy upstart), pursued an inappropriate methodology to populate its free tier (inhaling the open ecosystem in the style of various independent third-party apps), and triggered some perfectly predictable precautionary actions around licensing. In some ways, this feels like Luminary channeling, inadvertently or otherwise, an Uberian — Kalanickian? — approach to the podcast marketplace: act first, draw attention second, form partnerships third.

Still, I totally get how this looks like Spotify, the platform, firing off the first salvo to kneecap a potential competitor before it can even get going. But one should remember that Spotify is now also a big publisher, one that would generally like to know how its shows are being used to make someone else money without their explicit permission. Meanwhile, Anchor, which provides ad tech services to its hosting users, has also indicated a general doubt about Luminary’s relationship to third-party podcast advertising that appears to stem from a lack of proper outreach.

As Anchor CEO Mike Mignano told The Verge: “We’ve recently heard concerns from creators around Luminary’s very clear anti-ads stance, given that advertising is how most creators on Anchor make money…because Luminary’s business model is new, unproven, and frankly opaque in how it plans to monetize its free tier, we are being especially cautious regarding the potential to automatically distribute Anchor creators’ content, without knowing exactly how it will affect their podcasts.”

The “anti-ads stance,” of course, refers to the incident a few weeks ago when Luminary engaged in a branding campaign with a “Podcast don’t need ads” messaging. (There was a sign-bunny meme. It was a whole thing. I thought The Verge covered that detail really well at the top of its piece.) Anyway, Luminary has since reversed course on that approach, as evidenced by its current self-presentation as a dual-proposition — free pods and subscriptions — product.

oh shit what was their original tweet? pic.twitter.com/LfH8Vz14wz

— jeffrey cranor (@happierman) March 15, 2019

It was the bunny-holding-sign meme but it said "Podcasts don't need ads". The cached version from Discord is a bit janky looking as the formatting makes it want to create spoiler tags haha pic.twitter.com/0IB0y0WB5D

— Gavin | Podcaster, Writer, Train Enthusiast (@ThePodReport) March 7, 2019

| ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄|

| SOME |

| PODCASTS |

| DON'T |

| NEED |

| ADS |

| BUT |

| SOME |

| DO. |

| AND |

| THATS |

| OK |

|________|

(\__/) ||

(•ㅅ•) ||

/ づ— Fergus Ryan (@GusRyan100) March 7, 2019

We shouldn’t just fixate on the Spotify-Luminary dyad here; lest we forget, The Daily is also not on the platform at launch. There’s some nuance here. The New York Times told The Verge that it intends to be “judicious” about where The Daily is placed, and that it’s “looking forward” to working with Luminary…suggesting, once again, that this is a process issue, not a competition issue. Consider, also, that’s it’s only The Daily, the Times’ major audio money-maker and most sensitive asset, that’s being pulled off Luminary. You can still find other Times podcasts like Modern Love, Still Processing, and even Caliphate, a spinoff of The Daily, on there.

All these details, I think, contribute to the interpretation that rather than straight-up platform warfare, this Luminary launch brouhaha is about licensing. Specifically, this is about various entities wanting a properly executed process to make sure everybody’s square on who owns what, who owns what audiences and how, and how all sides can make money without interfering too much in each others’ lives. And as it stands, I wouldn’t be surprised if many other publishers outside of Spotify and The New York Times, big and small and medium-sized, might have the same desires too.

Which isn’t to say that podcast platform warfare isn’t on the horizon. For what it’s worth, I believe it’s inevitable. I just don’t think that’s what we’re looking at.

Anyway, three more things.

(1) Even if Spotify was aiming for the knees, I’m not sure it’s that big a deal? Moreover, if I were building a $100 million startup, I don’t think I’d want to build a business in such a way that not having access to five or ten major shows that I don’t own would be that big of a problem. To begin with, the podcast universe is huge and vast and still totally not existentially contingent on a few shows; one could easily outflank this problem with countless other shows and countless other communities. And furthermore, is the free tier truly necessary?

(2) There was a Digiday report last week that brought a mighty interesting Luminary data point to the table. Here’s the quote: “One source, who asked not to be identified, said Luminary was offering anywhere from $700,000 to $1.5 million per show, provided that show hit subscriber acquisition targets for Luminary.”

I’m hearing that this number range is, at the very least, imprecise. A source close to this matter tells me that the deal structure typically involves some combination of upfront payments — designed not to outbid the ad market — and performance-based payouts, both of which are sized differently based on the specific nature of the show. Sizing pre-existing shows is easier, as they have advertising track records that deals can peg numbers to. New shows, on the other hand, require projections. Luminary originals span a wide range of show types; so too, then, does the range of the deal sizes, which likely extends beyond the $700,000 and $1.5 million band in both directions, or so I’m told.

(3) Here’s the thing I’m thinking about with this licensing business: It’s all fine and dandy for bigger publishers, but I wonder how do smaller podcasters generally feel about being on the Luminary platform by default? Let me know.

Here’s a version I thought was interesting: Slate produced a narrated adaptation that was distributed through the Trumpcast feed, which featured Gabriel Roth and June Thomas reading aloud the report’s executive summaries.

“The idea came up a few weeks ago when we were planning our Mueller report coverage for the website — we thought our audience would appreciate the chance to hear some of the report in audio form,” Roth told me. “Trumpcast listeners, in particular, have been following the twists and turns of the Russia investigation avidly, and many of them probably won’t have a chance to read the full text of the report until the weekend, so it seemed like a useful service to give them the summaries in podcast form. (We did something similar with the audio from the Michael Cohen hearings in February.)”

The response appears to be good so far. “At least, as far as I can tell from Twitter and email,” Roth added.

Another format to note: Audible, which appears to have multiple recordings of the report. Here’s a free version that was developed as part of an initiative to create an archive of audio documents in the public interest, and here’s a not-so-free one produced by The Washington Post with additional material. (19 hours and 14 minutes, all told.)

Career spotlight. This week, I traded emails with Nick Liao — oh look, another cool Asian fellow in media named Nick! — who produces Good Food, KCRW’s great food radio program and podcast hosted by Evan Kleinman. The show recently received a James Beard Award nomination in the radio category for its tribute to the late Jonathan Gold, the Los Angeles Times’ beloved food critic who died last summer.

Liao wrote about his winding road into audio, having a complicated relationship with the notion of a career, and what radio brings to food media.

We’re also grateful for our longtime relationship with late Pulitzer Prize-winning food critic Jonathan Gold, who for two decades had his own restaurant-review segment on our program.

As managing producer, I wear as many hats as you’d expect for a lean, scrappy public radio show. I create rundowns, write scripts, edit audio, supervise music, work with freelancers, and help engineer recordings. I also oversee web content and socials plus external partnerships and live events.

My entrance into public media was in 2013, when I landed a news producer role with the PBS show Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly in D.C. (The show ended in 2017 after a 20-year run.) There, I learned the rudiments of much of what I do today: research and fact-checking, writing scripts on deadline, shaping rundowns, producing in the field, and booking studio conversations.

As that show was nearing its end, I pivoted to nonprofit communications for a short time, which turned out not to be a great fit. I missed producing and found myself listening to a lot of podcasts. So I decided to switch to audio, figuring that my TV producing experience would come in handy. Wrong! It was not an easy transition. I applied to jobs all around the country, only managing to land one interview with my local public radio station. I went to the Asian American Journalists Association conference in Vegas hoping to meet recruiters, but left without any strong leads.

Around that time in 2016, I was listening to a lot of Maximum Fun podcasts and ended up applying to MaxFun’s paid fellowship program on a whim. I got accepted, which was both thrilling but slightly terrifying. The job was in Los Angeles, and my wife and I were living in Cleveland at the time. After some handwringing, we sold our house and moved out to L.A. — a slightly more expensive city — for the gig. I was in my early 30s, and though we had some savings, I won’t lie: It was scary as hell.

Once at MaxFun, I found that audio editing came easily. I had messed around with DAWs in college, and I’d always been interested in audio gear from my teenage years playing music with friends. In one of my previous jobs, I had also edited a few podcasts on Audition. What MaxFun gave me was a chance to build a portfolio and network, and for that I’ll always be grateful.

That year, I co-produced The Turnaround with Jesse Thorn, a limited-run podcast spotlighting interviewers like Terry Gross, Errol Morris, and Katie Couric. I also helped create and manage the show’s partnership with the Columbia Journalism Review. After that, I was tasked with helping to launch the music podcast Heat Rocks, which is still one of my favorite shows. I also worked on NPR’s Bullseye and a few great comedy shows like One Bad Mother.

Towards the end of my fellowship, I spotted a job posting for the KCRW position on a Facebook group for Los Angeles area podcasters called Listen Up, Los Angeles! — an incredibly helpful resource if you happen to be around here.

It’s been a long journey, sometimes requiring a step backward in order to move forward, but everything kind of connects in hindsight.

In the future, I’d love to continue supervising shows, whether that’s one or many. As a writer with an entrepreneurial background, I’d love to create a project of my own at some point. Having worked in audio, TV, and print, I’m fairly agnostic about what form that could take.

Last year, we did a live show in New York where our host Evan Kleiman joined The Splendid Table’s Francis Lam for a tongue-in-cheek debate about pasta shapes with The Sporkful’s Dan Pashman as referee. No food was served, which I feared was a terrible mistake. But the venue was packed, and the audience was incredibly enthusiastic. One of the things I’m still surprised by is how much people love talking and hearing about food, abstracted from the visual appreciation or eating of it. You’d figure the subject is far better suited for video, but our listeners are really engaged.

As for what’s missing, I think many of us in food audio are still trying to innovate new formats and ways of telling stories beyond two-ways and traditionally reported segments. Though there are shows that I think are charting new ground, like Richard’s Famous Food Podcast, which is doing so in a fun and admittedly weird way.

In terms of non-food shows, I have to give a shout out to Long Distance, which is part of the Google Podcasts creator program with PRX. The show’s host and producer Paola Mardo is an exceptional talent who’s telling important stories about the Filipino diaspora. I’ve also been spending a lot of time with Dad Bod Rap Pod, kind of a panel discussion about the sort of rap music you might have been into if you were a backpack-wearing, socially awkward teen in the mid-to-late 1990s.

You can find Nick on Twitter, and KCRW’s Good Food here.