Welcome to Hot Pod, a newsletter about podcasts. This is issue 206, published April 30, 2019.

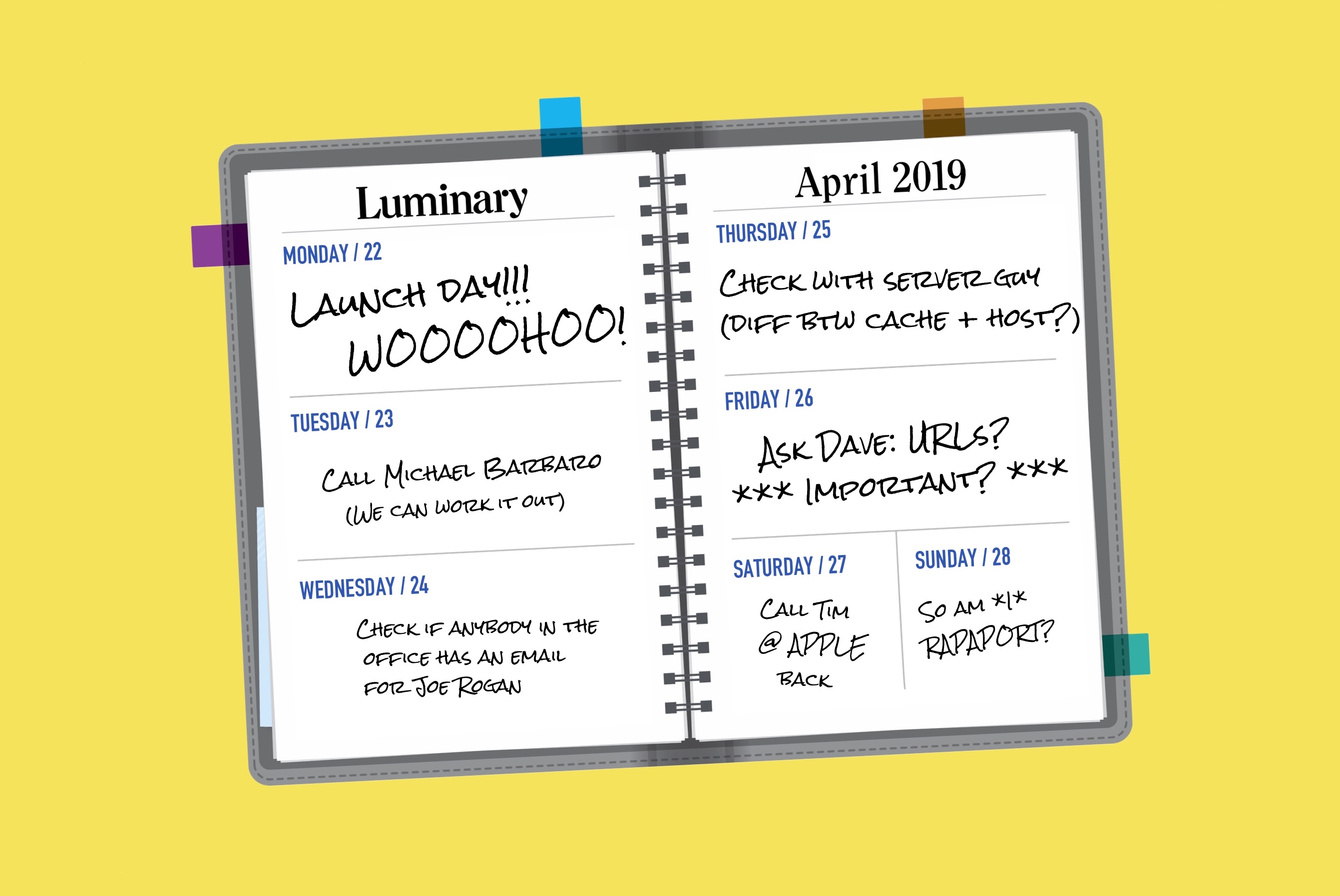

Luminary, seven days in. It’s been a full week since Luminary officially rolled out into the marketplace, and what a maelstrom it’s been. I’m sure many of you have been following the incremental updates as they spilled out into the open, but for the benefit of those who didn’t, let quickly recap to get us all of the same page.

When last Tuesday’s Hot Pod went out, the big headline had been the pre-launch pullouts of The Daily and Spotify’s various podcasting assets from the platform. The Verge, which broke the story, framed the move as the first overt sparks of some budding platform war. I didn’t fully share the interpretation, believing it to be more rooted in a procedural pushback over licensing and lack thereof. Since this time last week, Luminary’s rough rollout has worsened in multiple directions. To begin with, several other major podcast publishers followed The New York Times and Spotify’s lead in moving to pull their shows off the platform citing licensing issues, including The Joe Rogan Experience, Barstool Sports, and PodcastOne. (Though, again, the Times’ withdrawal is currently limited only to The Daily; its other shows are onboard.) But another node of controversy quickly emerged. On Thursday, a number of smaller and/or independently-minded podcasters — including Overcast creator Marco Arment and MacStories founder Federico Viticci, both prominent open publishing advocates — found that Luminary had been populating its free tier using an inappropriate technical methodology. That methodology, which involves the use of proxy servers, could send incomplete and non-IAB compliant listening data back to publishers as well as break dynamic advertising insertions. (Nieman Lab’s Joshua Benton has a great overview here.)Meanwhile, other podcasters, like The Greatest Generation’s Benjamin Ahr Harrison, had found that Luminary was altering their show notes on the platform, most notably taking out links. This is exceptionally problematic, because linking to sponsors and direct donation pages in show notes are fundamental aspects of how many podcasters, particularly smaller ones, do business. Many of those podcasters, too, joined the growing chorus of publishers requesting to be removed from the platform, ultimately broadening the arguments against Luminary’s free tier.

Luminary has since responded to the proxy server-related pushback, and subsequently said they were implementing the proper adjustments. But the company appeared to double down on its removal of show note links, citing “security concerns associated with the links.” This is a curious and questionable position, and once again, I’ll point you to another post by the dude Joshua Benton that effectively lays out why. All of that brings us to mid-Friday, which I capped off by publishing a summary/recap not unlike this one for Vulture.The publisher withdrawals continued, with two especially noteworthy additions: Stitcher and PRX. On Friday evening, Stitcher sent an email to its network of publishing partners informing them that the company had also decided to move to pull its owned and operated shows from Luminary and that they recommended those partners to do the same. That’s significant, of course, because Stitcher represents a considerable portion of the podcast industry in advertising sales and revenue efforts via Midroll Media.

When contacted for a statement, a Stitcher representative sent this over:

Stitcher has asked for its Stitcher Originals and Earwolf podcasts to be taken off the Luminary platform until we have had a meaningful discussion about how this arrangement might work. (The shows were added to the platform without our consent.) We have also offered to work on behalf of our partners — the shows we represent for advertising — to have similar discussions with Luminary for their shows. We look forward to continuing the conversation with Luminary. Our goal is always to keep our creators’ best interests at the forefront; we believe shows should be distributed on platforms where there is mutual benefit to the creator and the platform.

Note the use of the term “mutual benefit”; the concept was featured prominently in the email to partners, which several people forwarded to me.

Meanwhile, at around the same time, I learned that PRX had also moved to pull its podcasts off the platform. In case you need a refresher, PRX has a deep show portfolio that includes Radiotopia, Night Vale Presents, Gen-Z Media, The Moth, and a host of public-minded programs like Reveal and Scene on Radio.

Their decision to join the withdrawing ranks is notable for several reasons, but the biggest one is this: As an organization, PRX has long been vocal about its commitment to the open ecosystem.

(At this writing, both PRX and Stitcher’s shows are still listed on the platform.)

Luminary’s abysmal launch week didn’t simply end with more publisher withdrawals. By the weekend, the startup was dealt another blow to its lead generation efforts: Apple appears to have delisted several podcast feeds belonging to Luminary Original shows from its platform. They generally contained little more than a promo pointing listeners towards the Luminary app — but some of those podcast listings, like On Second Thought with Trevor Noah, could be seen floating around the Apple Podcasts charts as recently as Friday afternoon.

Okay — so now that we’ve laid all that out, let’s think through a few things.

Bad precedent? The cascade of publisher withdrawals — at first in response to a lack of license agreements, and then eventually branching out to include allegations of technical bad behavior — illustrates, among other things, that podcast publishers, even as a patchwork of different constituencies, can exhibit meaningful collective power against any one particular platform should the occasion arise.

But that reality has unnerved some corners of the podcast community, prompting the following question: Does this episode of publisher withdrawals set a bad precedent for podcasting? Or to frame the problem in more anxious terms: What’s stopping some politically aligned consortium of publishers from applying similar pressure to any other podcast app they’re not happy about at any point in the future?

Your mileage on this inquiry, I think, probably depends on the extent to which you buy into the justifications that are being offered by the withdrawing publishers.

There are different reasons powering different withdrawals, but if there’s a common theme, it’s a certain expectation around a notion of equal value exchange — that “mutual benefit” Stitcher was talking about. Though the two main camps — the ones who focus on licensing agreements and the ones who focus on Luminary’s lack of adherence to open publishing norms — approach the notion from different directions, both generally share a dubiousness that Luminary, as it stands, will give back in proportional measure to what it’s taking via its free tier — whether or not it’s RSS-compliant.

Let’s dig into that concept a little more. It suggests an environment where, should a given podcast app monetize content from the open podcast ecosystem that it doesn’t own (whether by one-time payment, visual advertising overlay, or whatever), that app should provide adequate value back — to the creators of that content in specific and/or the open ecosystem more generally. In most cases, this takes the form of sending usable analytics back to the creator (something Luminary stumbled on) and/or growing that creator’s audiences over the longer term. In other words, it’s the difference between mutualism and parasitism.

When phrased in these terms, you can rephrase much of what we’re talking about to a finer point: Many withdrawing publishers are working off a concern that Luminary is engaged in a parasitic long game — given its apparent strategy of using a free tier to drive its closed subscription-first business model (which will only bring value to itself, on a platform-level), its commitment to the Netflix-for-podcasts analogy, and its $100 million worth of venture capital motivation.

To be fair, it may well be the case that Luminary genuinely means well and/or truly intends a rising-tides-raise-all-boats framework. But for one reason or another — particularly the inappropriate tech methods and the way Luminary has handled the pushback in real time over the past week — the company has compelled many podcasters to become severely wary of it. (I’m still hearing from people who simply do not trust Luminary, believing they lack a fundamental level of transparency.) The pushback, then, along with the demand for formal licensing agreements, could be seen as defensive measures by some publishers to ensure some equal value exchange, should Luminary go on to build the future it wants using content it does own.

Whether or not you buy any of that justification is up to you. For what it’s worth, I generally don’t think there has or ever will be anything to stop any one entity or coalition from attempting to pressure any one podcast platform that they might not agree with — that’s just the reality of how power works. It’s just that, up to this point, podcasting has largely conducted itself in accordance to the spirit of open publishing, and that’s been powered by the fact that no single entity or coalition has been strong enough and/or motivated enough to attempt such a pressure campaign. Until now, perhaps.

(Before you say it, I’ll address the two exceptions. The first is Apple, whose defining oddity as a neutral ward in many ways allowed podcasting to flourish to begin with. The second being a seemingly similar debacle that surrounded early Stitcher years ago, when considerable corners of the podcast community took issue with the app’s technical methodology around distribution. The key difference there is that, unlike Luminary, Stitcher’s primary business model revolves around its ability to distribute other podcasts — Stitcher Premium came much later, and to this day remains a secondary concern — which, I think, structurally incentivized Stitcher to ultimately adhere to the demands of open publishing.)

Sounds depressing, no? I don’t know what to tell ya, other than to raise the question: Will the spirit of open publishing — or at the very least some spirit of good conduct — have enough political appeal and advocate to the strength of its norms over the long term?

Some final notes… Before I move off this topic, a couple of things on how I’m reading this story, which has proven to be a political lightning rod that’s crumpled a bunch of different narratives together.

Okay, that’s all I’ll say for now — unless another major development pops up.

Spotify paid ~$56 million for Parcast, according to the company’s Q1 2019 earnings report. That’s quite a bit lower than the “more than $100 million” sum reported by the Financial Times back when the news first broke in March. As VentureBeat pointed out, this brings Spotify’s overall podcast acquisition spending down to $400 million, theoretically leaving $100 million left in its stated $500 million podcast spending budget — which means that Spotify may well make another acquisition in the months to come. Then again, just because I set aside some cash for my vacation budget, it doesn’t mean I have to spend all of it at the beach…

I found this chunk of The New York Times’ writeup on the earnings report noteworthy: “It may take time for podcasts to have the desired effect on Spotify’s bottom line…[CFO Barry] McCarthy said Spotify’s investments in podcasts had created ‘a great deal of downward pressure on margins, at least initially as we built out the business.'”

Anyway, the Parcast angle isn’t the biggest news hook for Spotify’s Q1. Rather, it’s the fact Spotify has officially reached 100 million global paid users, a major milestone for both the company and streaming music platforms more generally.

Wondery has formed a “strategic partnership” with broadcast radio giant Westwood One, apparently to “create new audiences and advertising opportunities for the podcast industry.” The press release was a little vague on what this specifically entails, outside of an effort to repackage one of Wondery’s recent podcast projects, Sports Wars: Favre vs. Rodgers, as a three-hour broadcast special in early May.

RedCircle, a new startup that’s building a hosting platform to help “podcasts get promoted on other podcasts,” officially launched yesterday. The Verge’s Ashley Carman has the full details, but the key things to flag are: They’ve raised $1.5 million in seed funding, the team is mostly former Uber employees, and the apparent long game is to develop into an advertising platform for the podcasts it hosts. Always keep an eye on the long game.

Meanwhile, over at Edison Research… The firm is launching a new research product called the Podcast Consumer Quarterly Tracking Report, which seeks to function as a “bespoke” market research service for participating podcast companies. This is, one should note, the sort of research product that’s Edison’s bread-and-butter, the stuff that pays the bills.

Here’s how the company describes the product’s intent:

The Podcast Consumer Quarterly Tracking Report will provide charter members with a reliable and regular check-up on the podcast audience, what they are listening to, and the relative reach and awareness of the leading podcast networks. Each quarterly report will also track demographics, content preferences, listening behaviors (including clients and platforms) and other custom measures determined in consultation with all charter members.

Couple of things to flag:

Cool? Cool.

Acast acquires Pippa [by Caroline Crampton]. Acast, the Swedish podcast hosting and content company that recently raised $35 million in Series C funding, has acquired Pippa, a smaller podcast hosting and analytics startup, for an undisclosed sum.

Pippa — which vaguely resembles Anchor as a DIY hosting solution — has four employees who will now join the Acast team as the two platforms’ technology merges over the next few months. This deal has a few obvious benefits for Acast, but none more than the fact that Pippa is popular in several markets in which Acast wants to expand. (Primarily France, where they just opened a new office.)

Pippa also gives Acast reach into consumer paid-for hosting they currently lack, and thereby opens up more new shows for potential monetization. “[Acast] is a private marketplace, we have strict minimums that shows have to reach before they can join our platform,” Acast CEO Ross Adams told me when we spoke last week. “The part that was missing was a consumer-facing product. Part of the strategic mission of last autumn’s funding raise was to open up the platform and start looking at the long tail and monetization options for it. So we set out to buy or build, and we decided to purchase Pippa.”

However, it doesn’t seem like Acast is planning to immediately inject ads into every Pippa-hosted show. “Ad safety remains, of course, the highest priority here — we want to make sure that ads are going around the right content,” said Adams, before maintaining that they’re working on technical solutions to assist with that. “Pippa have a fantastic tool that transcribes audio to text and through that keyword search we know exactly what a podcast about, and what content is safe for advertising.” This integration is under construction, Adams noted, before emphasizing that there will always be a “vetting process” around what podcasts will qualify for monetization, presumably to avoid an ad appearing in podcasts that a brand would rather not be associated with.

The idea is that eventually Pippa-hosted podcasts will be able to turn on Acast’s suite of commercial tools if and when they reach a level of listenership that’s attractive to sponsors. Those tools would give them access both to dynamic insertion tech and, if desired, Acast’s team of salespeople in their various locations. It certainly makes sense for the company’s expansion — in the mostly non-U.S. markets they currently work in, there was always going to be a ceiling for the closed marketplace approach — and a consumer-facing product of this sort is a logical next step.

With the acquisition, Acast has likely doubled podcast inventory that they can monetize. But the thing I’m wondering is just how much of that inventory will actually be sellable, and therefore how lucrative all of this will actually turn out to be for the company. After all, if anything’s become clear in the past few years, it’s that cobbling a lot of DIY shows with small audiences together isn’t necessarily an reliable route to meaningful revenue.