Who said there’s no money in journalism? Sure, maybe the old ad model is decaying, and maybe hundreds of newspapers are on death watch — but the work-chat app Slack has been able to build a multi-billion-dollar business at least in some tiny part based on its remarkable uptake in newsrooms around the world.

Slack becomes a publicly traded company today — through a DPO (direct public offering) rather than an IPO (initial public offering), a screw-the-banks, help-our-current-employees-and-backers move that fits well with the early-web vibes the company has given off since launch. (CEO Stewart Butterfield previously co-founded Flickr; after Yahoo acquired it, he left that company with one of history’s most entertaining resignation letters. For me, he and other Slack folk like Cal Henderson and Matt Haughey have always evoked a kinder, gentler version of the Internet from the late 1990s and early 2000s, and I think you can find some of that DNA in the product today. I mean, its name is slack.)

Slack your coworkers — $WORK is public! #slack @FortuneMagazine pic.twitter.com/wMYuWkpSqH

— Anne Sraders (@AnneSraders) June 20, 2019

Slack launched in a limited beta in August 2013 and to the general public in February 2014, and some of the earliest and most eager adopters were newsrooms — particularly the tech teams inside news companies. We wrote our first story about it in June 2014:

The Internet has no shortage of chat platforms, and each has its own strengths. But for whatever reason, Slack seems to have grabbed a big share of the digital newsroom market in almost no time. (It was only released publicly in February.) Along with [The New York] Times, Slack’s in use at BuzzFeed, The Times of London, The Atlantic, Business Insider, Quartz, Slate, NBC News, The Guardian — and even here at Nieman Lab.

[Editor’s note: We love Slack and use it all day. —Josh]

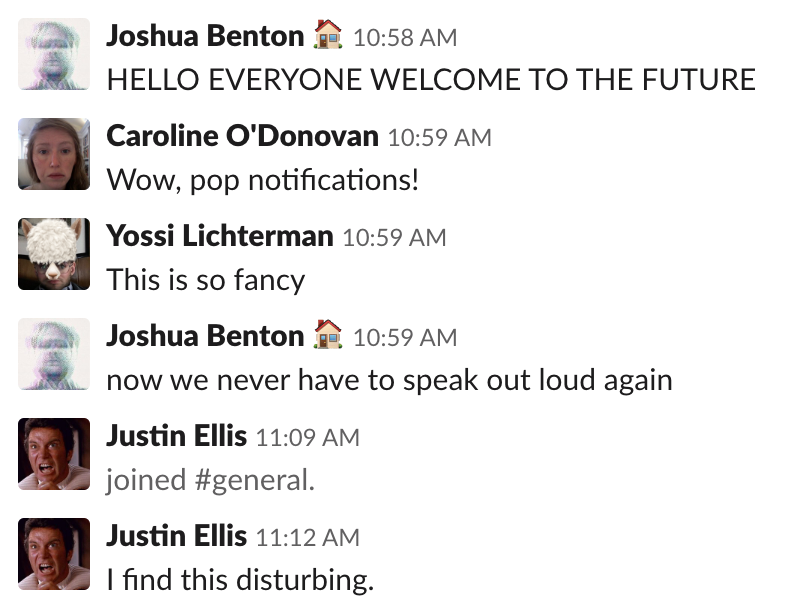

And yes, we did indeed start using it days after its public launch:

Slack has indeed become the central nervous system of many newsrooms, replacing endless email threads and becoming a friendly universal archive for information and documents. We’ve written 36 stories that at least mention Slack in some significant way in the years since, chronicling the various ways journalists and their colleagues have tried to use it — including:

— Slack as a way to convert internal chats into outward-facing content or liveblogs (a format that’s since been adopted more widely)

— Slack as a tool 7 different newsrooms integrate into their workflows

— Slack as a home for in-house newsroom tools to help with things like social promotion

— Slack as a news-distribution platform or as a subscriber benefit

— Slack as an audience-engagement tool for conversations with reporters or an archival discovery tool

— Slack as cross-newsroom collaboration tool

— Slack as a constructed reader community around a given topic

— Slack as a way to improve journalists’ use of analytics

— Slack as automated reporting tool

— Slack as a home for wayward ducks

At this point, there may be more newsrooms running on Slack than there are on Microsoft Word. While Slack has obviously grown beyond its initial success in newsrooms, the fact that it took hold among journalists early certainly didn’t hurt promotion. (Journalists like to talk about themselves, you may have noticed.) Slack’s stock-offering prospectus still highlights media companies as one of its most important user groups.

Today’s listing means that Slack is worth something like $17 billion. (For those scoring at home, that’s about 3× the value of The New York Times Company.)

Are there any lessons from Slack’s success that might apply to news companies? I can think of a few. Slack worked great on mobile devices from Day 1 and never viewed phones as a kid-sister platform to the “real” Slack on desktop. Slack built a great free product that let anyone sample it and get hooked — and then a smart upsell with clearly delineated benefits that made sense for heavy users. Slack realized that getting revenue from users is a more sustainable business model than selling their attention to advertisers, and they realized that companies have an easier time writing a big check than individual users do writing lots of small ones. Slack grew in large part through organic sharing, happy customers telling other people about it. And Slack solved a real problem — the tyranny of email — in a clear and easy-to-understand way. Those are all things that most media companies have been hit-or-miss on, and they’re all worth thinking about when building a news product.

But on this landmark day in Slack’s history, let me just, on behalf of journalists everywhere, send a grateful :heart_eyes_cat: and a heartfelt /giphy congrats in its general direction.