News organizations in wealthy countries cover climate change very differently from news organizations in poorer countries, according to a new report — and this hasn’t changed much over time, though a more detailed look at how news organizations worldwide are reporting on the issue shows some small signs of progress.

In a study published in the September issue of Global Environmental Change, researchers from the University of Kansas and Hanoi University of Science and Technology looked at how the media in 45 countries and territories framed climate change, and how that coverage was affected socioeconomic and environmental factors like GDP per capita, frequency of natural disasters, carbon dioxide emission levels, and press freedom levels.

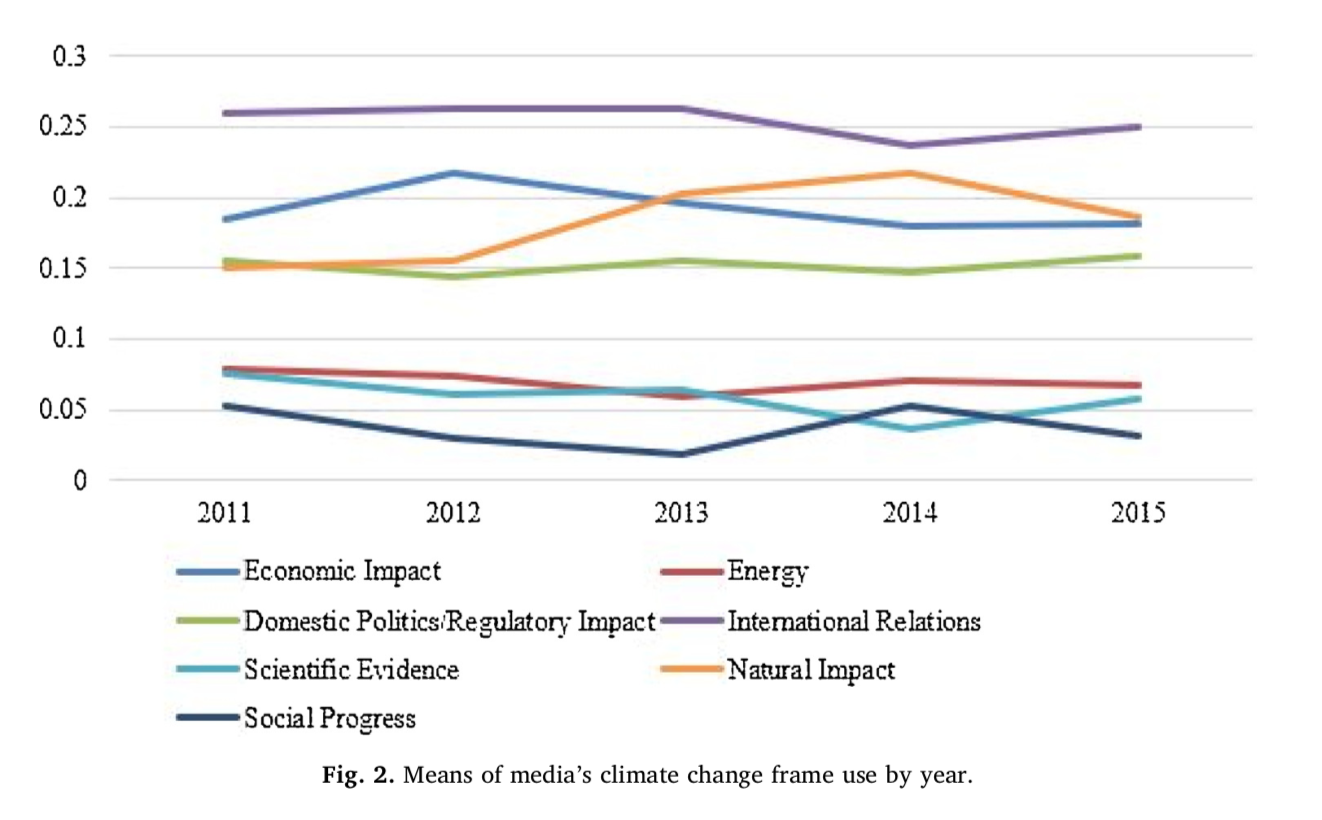

The total sample included 37,670 news articles, published between 2011 and 2015, from 84 publications (usually newspapers) in four languages (English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese). The researchers then classified the framing of each of the articles, assigning each one of seven frames: Economic Impact, Domestic Politics/Regulatory Impact, Scientific Evidence, Social Progress, Energy, International Relations, and Natural Impact.

Here’s what they found:

— I would have thought/hoped the framing of climate change coverage would shift over time (becoming more…urgent?), but it didn’t, at least not during four years covered in this study: Framing was largely consistent during the period. The urgency of climate change coverage continues to be a problem in the United States, and plenty of newspapers fail to cover it at all.

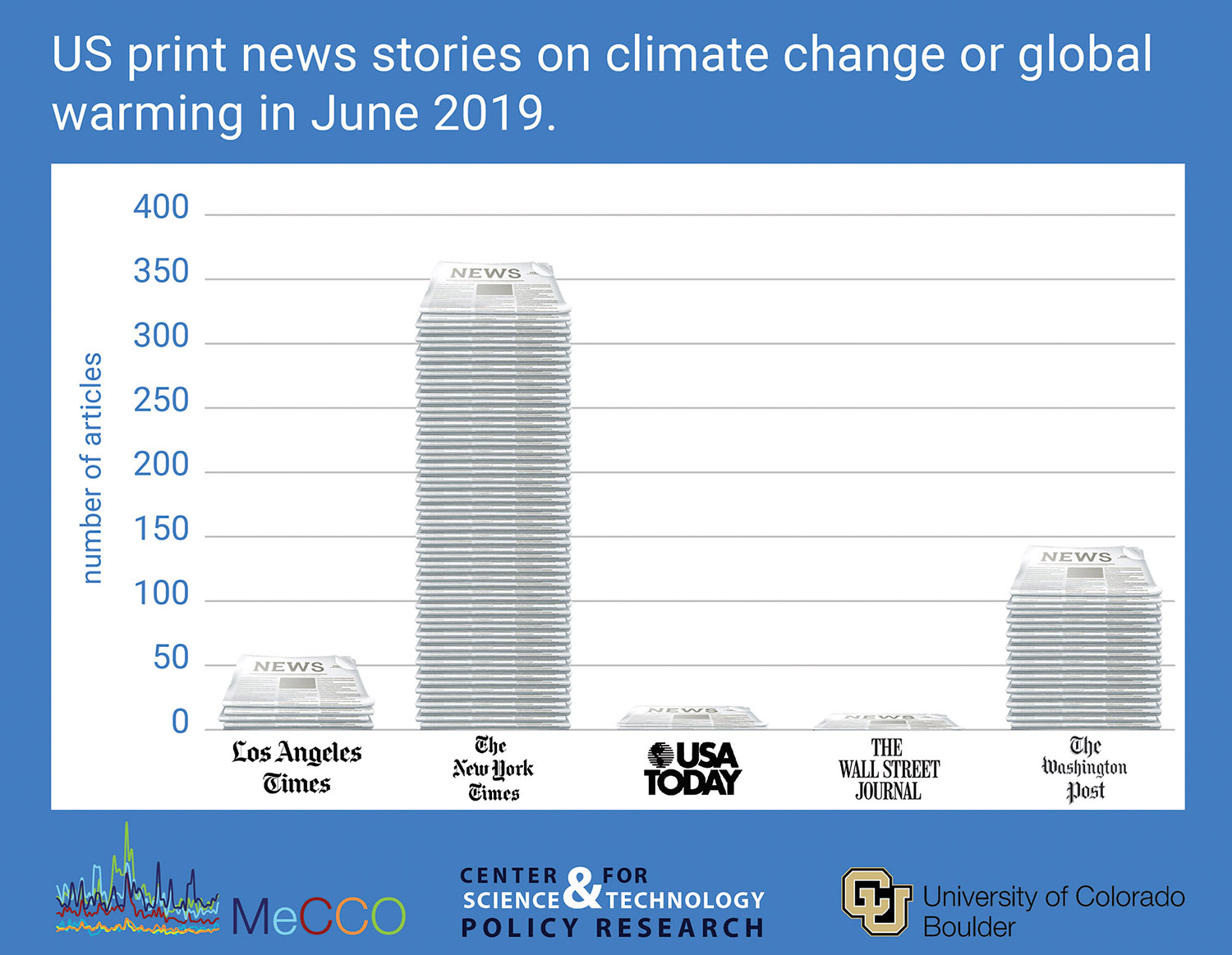

Coverage in the US was up 5% in print media and nearly 47% on television compared to the previous month. When this increase across outlets is disaggregated, one can detect a slightly different set of trends. These show that in fact most of these increases are due to increased coverage at The New York Times followed by increases at The Washington Post in print, and on CNN, Fox News and MSNBC in television, coverage. In fact, these increases across US media coverage of climate change in recent months are occurring in spite of rather than because of more abundant coverage in the leading US network news organizations — ABC News, CBS News, NBC News, and PBS Newshour — along with US prestige press outlets — The Wall Street Journal and USA Today.

— The wealthier the country, “the more likely its news media would frame climate change as issues of science and domestic politics…The press from richer countries are less likely to discuss climate change from the natural impact and international relations angles.” GDP per capita was the strongest predictor of a how a country’s media would frame its coverage.

The media from richer countries are more likely to frame climate change as an issue of domestic politics. This, perhaps, is because the voice of climate skeptics in richer countries gained stronger prominence in the media. In these countries, climate change is a highly contested issue with multiple groups, in their efforts of politicizing climate change, trying to influence the media agenda and policymaking. Additionally, the balanced reporting norm in the media in some democratic countries may have compelled journalists to include various views on climate change, thus affecting the public’s and decision makers’ perception of climate change. Such reporting practices also give a possible explanation as to why the media in countries with higher GDP are more likely to frame climate change as a domestic politics issue.

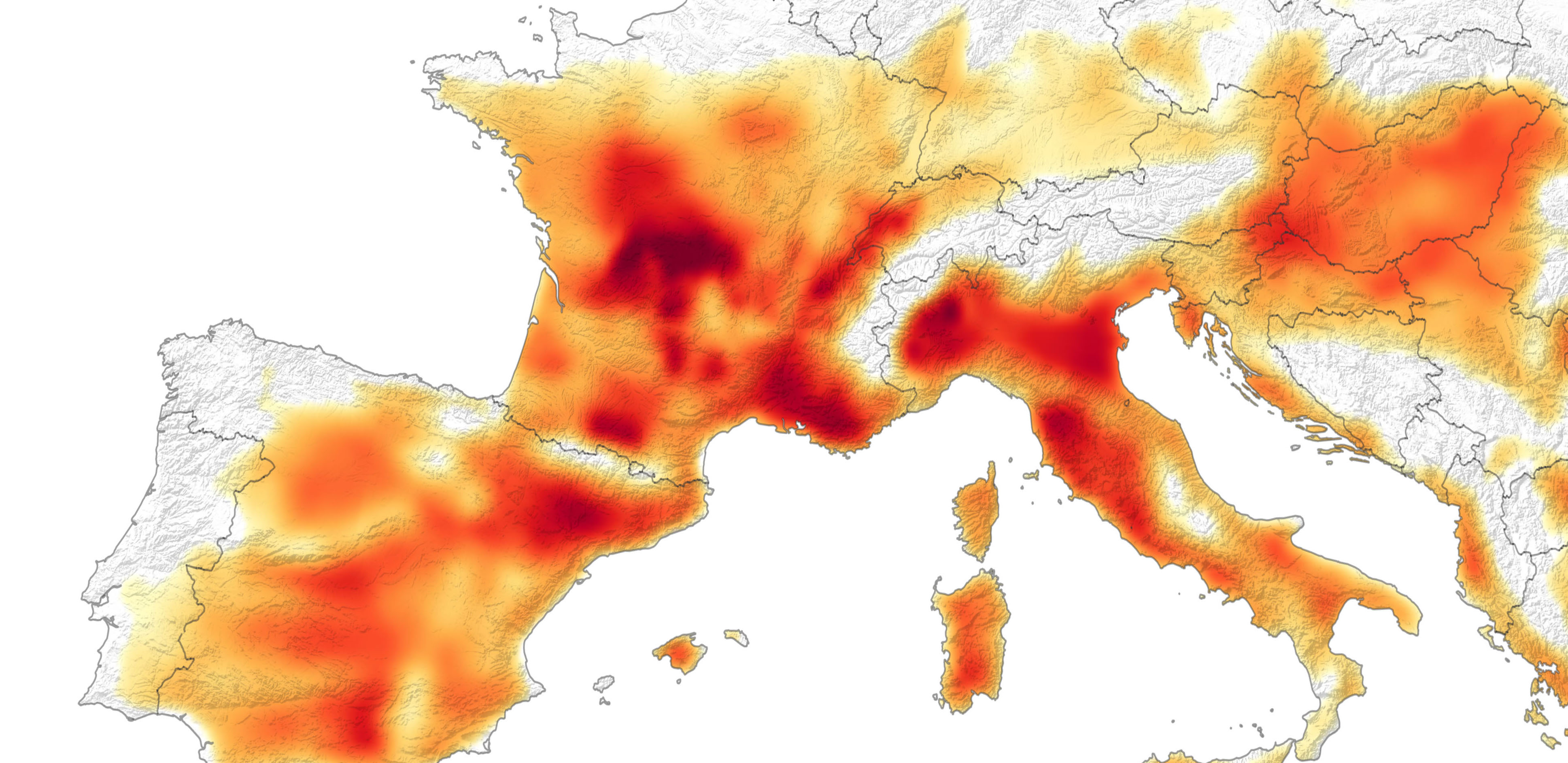

— The media in countries that frequently suffer from natural disasters “tend to frame climate change through the lens of natural impact”; countries that had more effective governments were less likely to frame climate change in the light of natural disasters. In June 2019, for instance, MeCCO found that climate change coverage in India was up 67 percent over the previous month, due largely to record-breaking heat waves and drought.

— Social progress was the least commonly used frame, with less than

four percent of content “devoted to covering new lifestyles or social developments related to climate change.”

You can read the paper here and follow MeCCO’s work here.