As the old newsroom saw puts it, a thousand planes landing safely isn’t a story. One plane that doesn’t is. That lens on newsworthiness has always given an edge to negative news — wars over peace, crimes over safety, fights over agreement.

We know by now that the audience doesn’t always care for those choices; many view the news as little more than a source of aggravation, helplessness, anxiety, stress, and general negativity. (This year’s edition of the Digital News Report features no fewer than 49 mentions of “negative” or “negativity.”) But we also know that negative stories — especially those that come with an emotional response baked in — are also the ones that people click on and share.That’s the context for an interesting new study out from three researchers at the University of Muenster, Florian Buhl, Elisabeth Günther, and Thorsten Quandt. They, like many academics these days, are interested in how stories spread — but in their case, they’re interested in how they spread from newsroom to newsroom, not among readers on social media.

They built a large dataset tracking every article published on the websites of 28 major German news publishers (“covering all major news outlets”) over a nine-month period in 2013-14. That’s 480,727 articles in all. They then combed through that newspile for stories that were covered by a large number of outlets — “events characterized by widely shared newsworthiness.” That narrowed things down to 95 events that were written about in 1,919 articles across the 28 news sites.

(Among the big international stories covered, in case you want to take a time machine to the Obama years: Amanda Knox, Nelson Mandela dies, shark attacks, MH370, Qatar gets the World Cup, Google sells Motorola, Uruguay legalizes pot, and “Mysterious mummy found in German attic.”)

With all that data, they were able to analyze how these stories spread from newsroom to newsroom — to calculate their “diffusion curves” — and what factors associated with stories helped to predict the speed and extent of that spread. They defined a number of characteristics each story could have: Is it a story from within Germany or outside of it? Are any of the people in the story a prominent well-known figure? Was the news unpredictable, or controversial? Did the outcome of the news event have major beneficial effects for anyone or any group?

As you would probably have been able to tell if I’d mentioned the paper’s title earlier — “Bad News Travels Fastest: A Computational Approach to Predictors of Immediacy in Digital Journalism Ecosystems” — the most significant pattern they could find in the data was that news about negative outcomes spread more quickly than other news. (The academic term of art used here is stories that are high in “damage,” which feels like an awesomely Germanic way to say it.)

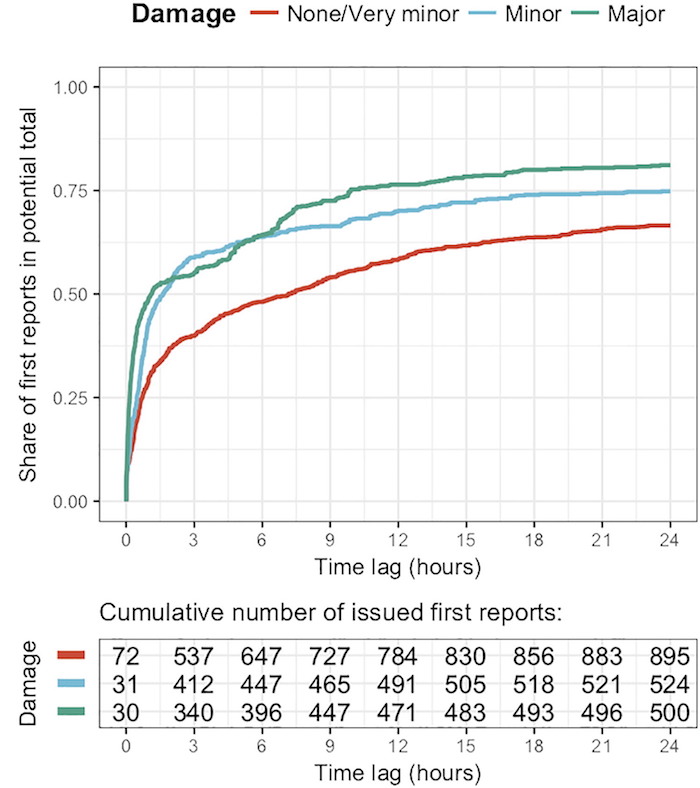

The aggregate diffusion curve of news about events causing no or very minor damage accumulates at relatively slow rates during the initial phase of diffusion (20.2% of potential first reports after 30 min, 33.6% after 90 min). In contrast, 42.2% of potential first reports on events causing major damage have been issued after only 30 min (25.9% on events causing minor damage). After 90 min, the shares of issued first reports in their potential total numbers are similar for events causing either major (52.3%) or minor damage (49.4%).

Interestingly, the study found that not many of the factors it identified had much of an impact at all: “We find that most news factors made no difference in a recurring pattern of basically fast diffusion dynamics. Only negative news and stories involving prominent personalities further accelerated diffusion processes and spread even faster.” So a celebrity death — high on both damage and prominence — is essentially peak spreadability.

What stories can slow down a story’s spread? One is obvious: If a story breaks in the middle of the night, when fewer reporters are on duty, it will take longer for it to spread. The other is interesting: News events “characterized by wide reach beyond small groups…slowed down digital diffusion.” That is, a story that primarily impacts individuals or small groups will spread more quickly than one that primarily impacts “the middle class” or “workers” or “society”: “The wider the range of people affected by an event is, the less likely rapid, wide-range diffusion of the story is from the start.”

It’s not particularly shocking that bad news spreads most quickly. Aside from whatever deep ev-psych patterns may be at play, a big negative story is also the sort of thing an editor wouldn’t want to be missing. They also tend to be more readily replicable; if someone’s dead, that’s easier to confirm in 20 minutes than a story about political intrigue.

But I do despair a bit at the thought of all those journalist person-hours spent writing relatively rote follows to a story some other paper had. Thirteen outlets spent time on that attic-mummy, which turned out to be not so Egyptian and to have bones made out of plastic. (Though a real human skull. Creepy!) And the fact that stories that impact more people spread more slowly says something about our collective desire to reduce complicated phenomena into individual, human stories. (Think of how the climate-change stories that sometimes breakthrough are often those that focus on its impact on a single community.)

As the researchers conclude:

We consider this study a promising example of how an analytical ecosystem approach aided by computational methods and a broad media sample can further our understanding of digital newswork. Specifically, our results suggest journalism research should not take the logic of classic theories such as news values for granted when applied to novel phenomena. We hope our glimpse into the sophistications of online news production from a process perspective will inspire future research to complement the shortcomings of this study and to further untangle the interplay of technological and professional opportunities and affordances in digital newsrooms.

For example, researchers could outline and test more fine-grained indicators for the prominent elements of stories news users easily relate to (e.g., categories of people, sites, or actions). Likewise, researchers could distinguish between events confirming the status quo and events indicating crucial turning points in the development of an established issue, hence necessitating prompt coverage.

You can download the dataset used in this study here.