More often than not, the news sucks. It’s depressing and disappointing (but hey, so is real life sometimes), and it’s clear that the negative Nellie Blys of the world help push away potential news consumers who can now easily scroll away from a scary headline or recoil from TV news airing in public.

Almost a third of people surveyed worldwide for the Reuters Digital News Report said they “often or sometimes” avoid the news. Why? The leading cause for Americans avoiding news in 2017 was “It can have a negative effect on my mood” (57 percent) and “I can’t rely on news to be true” (35 percent). Basically, we are bumming — and burning — people out.

In presenting that data here at Nieman Lab earlier this summer, Joshua Benton rounded up thoughts from would-be news consumers followed by this point:The solutions journalism people should be sending this article to all potential funders, because the problem they’re trying to address shows up crystal clear here: News about big problems is depressing if I’m not presented with potential solutions. Regular news consumption can engender a kind of learned helplessness that make clear the appeal of ideologically slanted news — which offers up a clear cast of good guys and bad guys with no moral gray — and just avoiding news entirely.

Solution time: Researchers at the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin analyzed how solutions journalism can be presented effectively. Try including these five specific elements in your next article:

Just remember PSIRI! Or SPIRI, or ISPRI, or something.

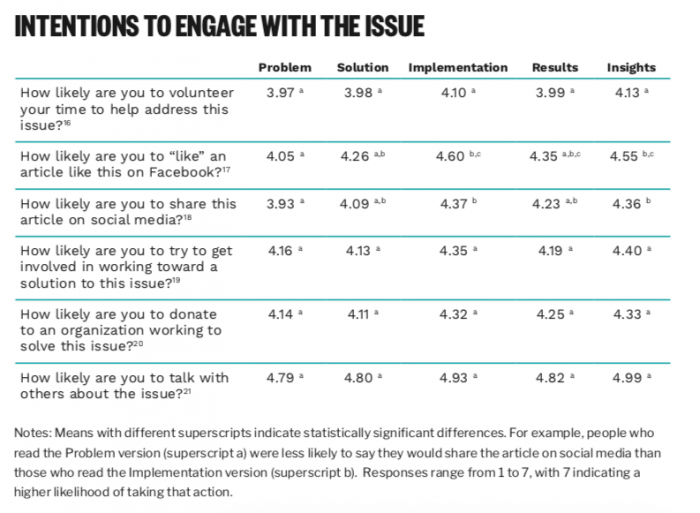

Caroline Murray and Talia Stroud found that articles with all five elements improved readers’ perception of the quality of the article and personal positivity and increased their intention to engage, interest and knowledge about the issue, and their intentions to read more articles about the issue. It’s kind of a win-win.

“When it comes to solutions journalism, the more information you can provide readers, the better. Adding additional components beyond the problem and the solution (i.e. implementation, results, and insights) can bolster positive responses to your work,” Murray and Stroud write. “However, parts of this project also suggest that the addition of components beyond the problem and solution is only influential when news organizations provide comprehensive reporting on these first two components. [Emphasis ours.] Without this foundation, the effect of the other three components is weakened. It is important that journalists take the time to fully explain the issue and the response before exploring implementation, results, and insights.”

It’s no inverted pyramid, but it’s pretty straightforward. Bring readers all onto the same playing field of context about an issue, and don’t just cut away to the solution when they don’t understand the stakes for it. (At the same time, of course, don’t drag it out so much that they leave before getting to it.) And follow through with more details for what it actually looks like.

Murray and Stroud tested the preferences and comprehension of participants in a three-part experiment. First they had 2,100 testers read articles from the Guardian and the NPR containing a mix of the solutions journalism components and then quizzed them on their attitudes and emotional responses to the article they read. The higher the number, the better:

The researchers also experimented with 225 volunteers from the readership of Richland Source, an independent local news site in Ohio, and also Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Some testers read an article just about the problem, some read it with some elements, and some read a comprehensive article with all five elements included. The two groups felt that they could contribute a solution to the problem and increased the user’s interest in the issue, though the more comprehensive approach was indeed more effective.

Looking for the insight? You’ve been reading an article following those five steps all along.