Is that print newspaper getting read, or is it just sitting on a subscriber’s coffee table?

For most print publishers, there’s no way to know how or whether that stack of newsprint is consumed before it’s recycled. The analytics available to track the habits of online readers — those privacy-problematic trackers that see how much time someone spends on a page or how far down they get in an article — simply aren’t available for print.

At least, until now! Lesewert is a German company that aims to help publishers track how readers are consuming print newspapers and magazines: which topics they’re turning to first, which articles they’re reading in full, whether they’re noticing sidebars and pullouts, which days of the week they read the most, and so on. The data can then be further broken down by gender, age, and other demographics.

Lesewert is part of the German publishing analytics firm Die Mehrwertmacher (“The Value-Added”), a subsidiary of the regional publishing company DDV. DDV’s newspaper in Dresden daily newspaper, Sächsische Zeitung, was the first newspaper to use Lesewert. It’s since brought on other German newspapers and media companies as clients, having added its first international customer, the Luxemburger Wort, in 2017. (One of the findings there: The paper was too long. When it began publishing fewer articles in its print edition, average reading time actually went up.)

“We built it for ourselves, but it aroused a great deal of interest in Germany,” said Ludwig Zeumer, Die Mehrwertmacher’s CEO.

Here’s how it works: Clients pull together focus groups, generally about a hundred people, Zeumer said. Members of those groups are each given a digital pen that looks like a fat highlighter and is equipped with a little camera and a light. They’re asked to use the pen every time they read the newspaper over two or three months, using the digital pen to mark the last line of text in each article they read.

That data is then transmitted to an app and compiled into a dashboard that publishers can log in to see what people are reading and how; for each article, Lesewert calculates a “reading value” score, which brings together the data on how many print readers at least noticed an article and how much of it they read (spoiler alert: they often don’t read to the end) into a single score. Publisher clients can compare all that data to find out which of their stories are performing the best, which topics draw the most interest, which layouts encourage the most reading, and so on.

One not-so-surprising finding is that people aren’t reading print newspapers cover to cover. “We figured out that generally people are reading like 1/4 of the newspaper, and not all newspapers are being read,” Zeumer said.

From 2014 to 2016, for instance, Lesewert worked with the famed German weekly news magazine Der Spiegel. Based on the data collected through Lesewert, Spiegel decided to move its print publication day from Monday to Saturday. Sächsische Zeitung, meanwhile, was in the habit of publishing more articles on Saturday than any other day of the week — until data showed that “reading value” that day was lower than any other day of the week.

While print lacks the measurability of digital, there have long been efforts to try to get more granular data on the habits of newspaper readers — dating back to the work of Leo Bogart, Ruth Clark, and more. But those were typically either survey-based, small in scale, or both. Article-level information about print reading was also part of the promise of the oft-mocked CueCat, the cat-shaped barcode reader that a number of newspapers and magazines bet on in 2000. Consumers were expected to read their morning paper CueCat in hand — not too far from their giant beige PC, since the device wasn’t wireless — and swipe it over story barcodes that would open up a web browser with additional information of some kind. It was a notorious flop. But getting a focus group to do the extra work is a better bet than expecting your customers to.

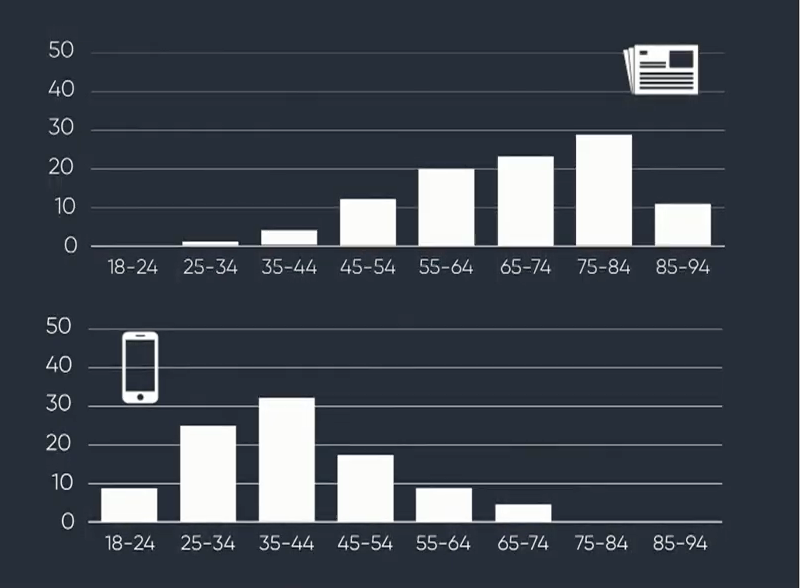

Sächsische Zeitung is currently running tests with Lesewert to decide how to consolidate its local print editions — it currently publishes 20 and wants to cut number that in half — while gaining online subscribers. In a presentation at the European Publishing Conference earlier this past spring, Sächsische Zeitung editor-in-chief Uwe Vetterick showed the audience a chart revealing the disconnect between the paper’s print subscribers and digital readers: Its largest group of print subscribers is between the ages of 75 and 84, while online users skew about four decades younger, but don’t necessarily pay.

“We call this in Germany the Chart of Silence,” said Vetterick. “It’s called the Chart of Silence because when you show it for the first time, all of a sudden everyone was so silent. This is the truth…almost half the readers of our papers are approaching their 80s or 90s. The average age of those newly subscribing [to print] is 64. This is our situation.” The paper showed that just about 20 percent of online articles on local topics were driving 80 percent of new subscriptions from that coveted thirtysomething demographic.

Sächsische Zeitung began experimenting with online-first models in two of the towns where it publishes local editions, Löbau and Zittau. By testing print reader reaction throughout the process — before, during, and after the switch to print editions that are filled only with stories that have run online — Sächsische Zeitung was able to make sure it wasn’t losing them. Results have been good: “Reading value” scores in the Löbau print edition increased by 12 percent after the conversion to online-first, while the scores increased by 6 percent in Zittau.

“They wanted online first,” Zeumer said at the European National Congress, “and in the end even got a better newspaper.”

A previous version of this article stated that Lesewert clients sometimes use its data to cut print days. The company clarified that none of its clients have cut print days yet.