The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

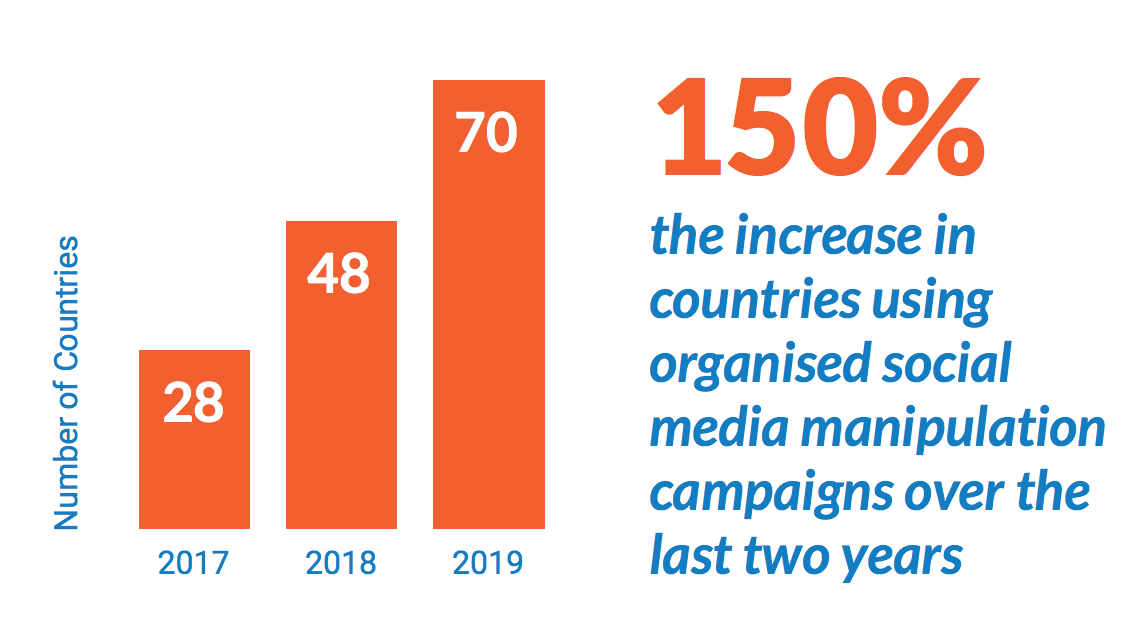

“The number of countries with political disinformation campaigns more than doubled to 70 in the last two years.” The University of Oxford’s Computational Propaganda Research Project released a report about “organized social media manipulation campaigns” around the world. Here’s The New York Times’ writeup too.

One of the researchers’ main findings is that Facebook “remains the dominant platform for cyber troop activity,” though “since 2018, we have collected evidence of more cyber troop activity on image- and video-sharing platforms such as Instagram and YouTube. We have also collected evidence of cyber troops running campaigns on WhatsApp.”

Important to note that more countries used human operators than bots.

Surprising how few used hacked or stolen accounts, given how easy these can be to buy.

Watch for more of this. pic.twitter.com/Dh8pMJh0vK

— Ben Nimmo (@benimmo) September 26, 2019

The study finds evidence of #comprop by 26 authoritarian regimes to shape public opinion & suppress human rights. In this landscape, China has become a major player after the protests in #HongKong with increasing interest in foreign platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

— ComProp Research (@polbots) September 26, 2019

WhatsApp’s message forwarding limits work somewhat, but don’t block misinformation completely. WhatsApp limits message forwarding in an attempt to prevent the spread of false information. As of this January, users worldwide were limited to forwarding to “five chats at once, which will help keep WhatsApp focused on private messaging with close contacts.”

So does the forwarding restriction work? Researchers from Brazil’s Federal University of Minas Gerais and from MIT used “an epidemiological model and real data gathered from WhatsApp in Brazil, India and Indonesia to assess the impact of limiting virality features in this kind of network.” They were only able to look at public group data, not at private conversations.

Here’s what they did:

Given a set of invitation links to public groups, we automatically join these groups and save all data coming from them. We selected groups from Brazil, India and Indonesia dedicated to political discussions. These groups have a large flow of content and are mostly operated by individuals affiliated with political parties, or local community leaders. We monitored the groups during the electoral campaign period and, for each message, we extracted the following information: (i) the country where the message was posted, (ii) name of the group the message was posted, (iii) user ID, (iv) timestamp and, when available, (v) the attached multimedia files (e.g. images, audio and videos).

As images usually flow unaltered across the network, they are easier to track than text messages. Thus, we choose to use the images posted on WhatsApp to analyze and understand how a single piece of content flows across the network.

In addition to tracking the spread of the images, the researchers also looked at the images’ “lifespans”:

While most of the images (80%) last no more than 2 days, there are images in Brazil and in India that continued to appear even after 2 months of the first appearance (105 minutes). We can also see that the majority (60 percent) of the images are posted before 1000 minutes after their first appearance. Moreover, in Brazil and India, around 40 percent of the shares were done after a day of their first appearance and 20 percent after a week[…]

These results suggest that WhatsApp is a very dynamic network and most of its image content is ephemeral, i.e., the images usually appear and vanish quickly. The linear structure of chats make it difficult for an old content to be revisited, yet there are some that linger on the network longer, disseminating over weeks or even months.

And here’s what they found:

Our analysis shows that low limits imposed on message forwarding and broadcasting (e.g. up to five forwards) offer a delay in the message propagation of up to two orders of magnitude in comparison with the original limit of 256 used in the first version of WhatsApp. We note, however, that depending on the virality of the content, those limits are not effective in preventing a message to reach the entire network quickly. Misinformation campaigns headed by professional teams with an interest in affecting a political scenario might attempt to create very alarming fake content, that has a high potential to get viral. Thus, as a counter-measurement, WhatsApp could implement a quarantine approach to limit infected users to spread misinformation. This could be done by temporarily restricting the virality features of suspect users and content, especially during elections, preventing coordinated campaigns to flood the system with misinformation.

Should politicians be allowed to break platforms’ content rules? (If so, which politicians?) The politicians will not be fact-checked: Facebook’s Nick Clegg said this week that “Facebook will continue to exempt politicians from third-party fact-checking and allow them to post content that would otherwise be against community guidelines for normal users,” per BuzzFeed. Clegg — a longtime politician himself — provided more detail in a Facebook post:

We rely on third-party fact-checkers to help reduce the spread of false news and other types of viral misinformation, like memes or manipulated photos and videos. We don’t believe, however, that it’s an appropriate role for us to referee political debates and prevent a politician’s speech from reaching its audience and being subject to public debate and scrutiny. That’s why Facebook exempts politicians from our third-party fact-checking program. We have had this policy on the books for over a year now, posted publicly on our site under our eligibility guidelines. This means that we will not send organic content or ads from politicians to our third-party fact-checking partners for review. However, when a politician shares previously debunked content including links, videos and photos, we plan to demote that content, display related information from fact-checkers, and reject its inclusion in advertisements. You can find more about the third-party fact-checking program and content eligibility here.

YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki said something similar: “When you have a political officer that is making information that is really important for their constituents to see, or for other global leaders to see, that is content that we would leave up because we think it’s important for other people to see.”

A YouTube spokesperson, however, told The Verge that Wojcicki’s remarks were “misinterpreted”:

The company will remove content that violates guidelines regardless of who said it. This includes politicians. But exceptions will be made if it has intrinsic educational, news, scientific, or artistic value. Or if there’s enough context about the situation, including commentary on speeches or debates, or analyses of current events, the rep added.

Some criticized Facebook, in particular, for letting politicians get away with worse behavior than anyone else. Others, notably former Facebook chief security officer Alex Stamos, argued that the policy is reasonable because it isn’t Facebook’s place to “censor the speech of a candidate in a democratic election.”

Sorry haters but this is a sensible policy. Voters deserve unfiltered access to the statements of elected officials and their challengers. https://t.co/tlt5b87fW5 pic.twitter.com/KFfGySCgsn

— Timothy B. Lee (@binarybits) September 25, 2019

So who, specifically? And who gets that power?

The "these companies should control political speech by politicians in democracies" argument is completely incompatible with everything the same proponents say about antitrust, platform power and unaccountable executives.

— Alex Stamos (@alexstamos) September 24, 2019

This isn’t cleaning up oil spills, it’s “Standard Oil should use their dominance to choke Union Pacific because I don’t like their labor policies”.

Asking intermediaries to make choices like this grants them power that we normally reserve for transparent, democratic processes.

— Alex Stamos (@alexstamos) September 24, 2019

Curious who gets to be a “politician” under this definition. Are fake candidates running for the lulz now going to be taken seriously under this policy? https://t.co/26ALx9PB5I

— Renee DiResta (@noUpside) September 24, 2019

In The Washington Post, Abby Ohlheiser looked at how platforms are grappling with questions of “newsworthiness,” wondering, for instance:

“Newsworthiness,” as a concept, is inherently subjective and vague. It is newsworthy when the president tweets something; what about when he retweets something? Multiple times in recent months, Twitter has taken action against accounts that have been retweeted or quote-tweeted by @realDonaldTrump. When the president retweeted a conspiracy-theory-laden account claiming that “Democrats are the true enemies of America,” the account itself was suspended, causing the tweet to disappear from Trump’s timeline. At this point, it is not clear what makes Trump’s tweets, but not those he amplifies to his millions of followers, newsworthy.