Welcome to Hot Pod, a newsletter about podcasts. This is issue 230, dated October 15, 2019.

Mina Kimes will host ESPN’s upcoming daily sports podcast. A senior writer who also frequently appears as a contributor on ESPN’s various television properties, Kimes joined ESPN in 2014 following stints at Fortune and Bloomberg News. She already hosts another podcast for ESPN, The Mina Kimes Show featuring Lenny, which will continue production. (Lenny, by the way, is her dog.)

The appointment is part of “a new multiyear agreement,” according to the official press release, which says the upcoming project will use a “narrative-driven approach” that’s become common in the daily podcast genre.

Also announced: The podcast will debut on October 21, featuring Dell and Indeed as presenting sponsors. And in case you didn’t know, the show will be called ESPN Daily, not to be confused with the company’s daily newsletter of the same name… or The Daily, for that matter.

For what it’s worth, ESPN isn’t first-to-market as far as “narrative storytelling-oriented daily sports podcasts from sports media companies” are concerned. That honor probably goes to The Athletic, which launched its own daily audio show called The Lead in partnership with Wondery last month.

The move is tied to two specific goals. First, it’s meant to better align Midroll’s metric reporting with the IAB Podcast Measurement Technical Guidelines 2.0, which continues to be the standard many in the industry are working to rally advertisers around.

Second, the change is associated with Midroll’s plans to move into “full-catalog” sales — that is, selling ads not just on current and future episodes, but using dynamic ad insertion to effectively bundle together inventory from past episodes as well. This is the most noteworthy chunk of this development, as the move would bring Stitcher further in line with the broader podcast ecosystem’s ongoing efforts to modernize its advertising capabilities to make it more appealing to a broader pool of advertisers.

This eye on sales modernization is specifically reflected in Stitcher’s stated reasoning when explaining the switch to Omny. In the email circulated to partners, the company highlighted the platform’s ability to target ads to specific listeners, which it calls “a significant advertiser request.”

On a related note…

Wondery strikes two more international ad sales partnerships. One is with Ranieri and Co., which will represent Wondery’s inventory in Australia and New Zealand, and the other is with Audio.ad, which will rep the company in Latin America and Brazil. With these partnerships, Wondery is no longer working with Acast on monetization in any market.

Megaphone has hired a new CFO: Cameron Jones, who joins the Graham Holdings-owned podcast hosting and ad tech company from Revolt TV & Media, the independent L.A.-based digital cable TV network. Been a while since I’ve heard from Megaphone!

VoxFronts. Tonight, Vox Media will hold an event for its growing podcast business at a (fairly swanky) space near its downtown Manhattan offices, which it’s billing as its first official podcast upfront. On the menu, aside from the customary hors d’oeuvres, are details on several new upcoming projects. Among them:

Anyway, Reset, Vox Media’s big tech news podcast franchise that I wrote about last month, officially launches today, and the weather in New York is projected to be mild these evening, ahead of tomorrow’s rainfall.

Studio 360 with Kurt Andersen is coming to an end, PRX announced last week. Andersen will wrap his full-time role with the production at the end of the month. The final episode is set to air next February, tying up a nearly two-decade run, and the show’s digital audio archive will be made permanently available for on-demand consumption.

PRX would not provide a specific reason for the show’s wind down, with chief operating officer John Barth citing “a variety of factors.” Originally a co-production of PRI and WNYC when it launched in 2000, Studio 360 became a PRI and Slate co-production in 2017 when WNYC decided to refocus its efforts and resources into projects it completely owns. It came into PRX as a result of the PRX-PRI merger last summer.Pour one out for Studio 360, which was a pretty consequential institution, talent-wise. A decent number of producers working in public radio and private podcasting today came through Studio 360 at one point or another, and more than a few ended up as front-of-mic personalities. One tiny example: Sean Rameswaram, currently the host of Today, Explained, once hosted a Studio 360 spinoff podcast called Sideshow.

On a related note: Studio 360 wasn’t the only WNYC-affiliated show that came to a close last week. Last Friday, the New York public radio giant announced that it will end New Sounds, its beloved and long-running music show of 37 years hosted by John Schaefer, by the end of the year. According to The New York Times, which first reported the news, the station is also planning to close “most of its remaining music programming, as it shifts to more news and talk.”

All things must come to an end, I suppose.

The Third Coast Festival has announced the 2019 winners for the Third Coast/Richard H. Driehaus Competition. Here’s the list.

Will podcast playlists elevate the “microcast”? [by Cherie Hu] While digging through my Spotify profile this past weekend, I came across an intriguing discovery: Gimlet has been republishing five- to seven-minute excerpts of its podcast Science Vs as new, standalone episodes, made specifically to fit into the algorithmic playlist Your Daily Drive on Spotify. These shorter episodes are set aside as an entirely different show on the platform titled Shots of Science Vs, with the caption “Science Vs for Your Daily Drive.”

It’s an intriguing move — one that, I think, may well be an indication of where a certain kind of podcasting could go.

Spotify officially launched Your Daily Drive back in June. For the uninitiated, the feature is a hybrid music-slash-podcast playlist designed to be consumed within the context of a commute. And more importantly, it’s meant to be algorithmically personalized for each individual user. The flow of a standard Daily Drive playlist typically consists of one brief podcast episode, lasting around five minutes on average, followed by four musical tracks, then that same sequence repeated six more times with different episodes and songs. Featured podcasts range from news updates from NPR, The New York Times and the BBC to evergreen true-crime, science, and culture stories.

The Swedish audio platform had been experimenting with weaving music and other forms of audio into a single playlist since 2016, the year the company launched the music-centric hybrid playlist franchises AM/PM and Secret Genius. Both of those playlists alternated contextual, podcast-esque commentary from artists and songwriters with tracks that they wrote, performed and/or curated.

AM/PM stopped production in 2017, and Secret Genius hasn’t updated its podcast since November 2018 (likely in part due to ongoing legal conflicts with songwriters and publishers). But the hybrid music/podcast playlist lives on through channels like Your Daily Drive, and more recently, through the more open podcast playlist creation tool that Spotify announced in September 2019, which allows any user to curate songs and podcasts side-by-side. The feature isn’t even a month old yet, but we’re already seeing audio and music production companies modifying their output to fit podcast playlists.

Science Vs presents an illustrative case study. On average, original episodes of Science Vs tend to last between 20 to 40 minutes each. That’s arguably too long in the context of a playlist, especially one like Your Daily Drive, where users expect tracks to flow quickly and smoothly from one to the next, given the limited amount of time they have to listen.

So what does Gimlet, nowadays organized under the Spotify Studios label, do? They cut out and feed the most interesting soundbites from its shows into Your Daily Drive, rather than entire episodes, for a more music-like user experience. The original length of the episode “Heartbreak: Why does it hurt so bad?” is around 17 minutes, but the version fed into the algorithmic playlist lasts under 6 minutes.

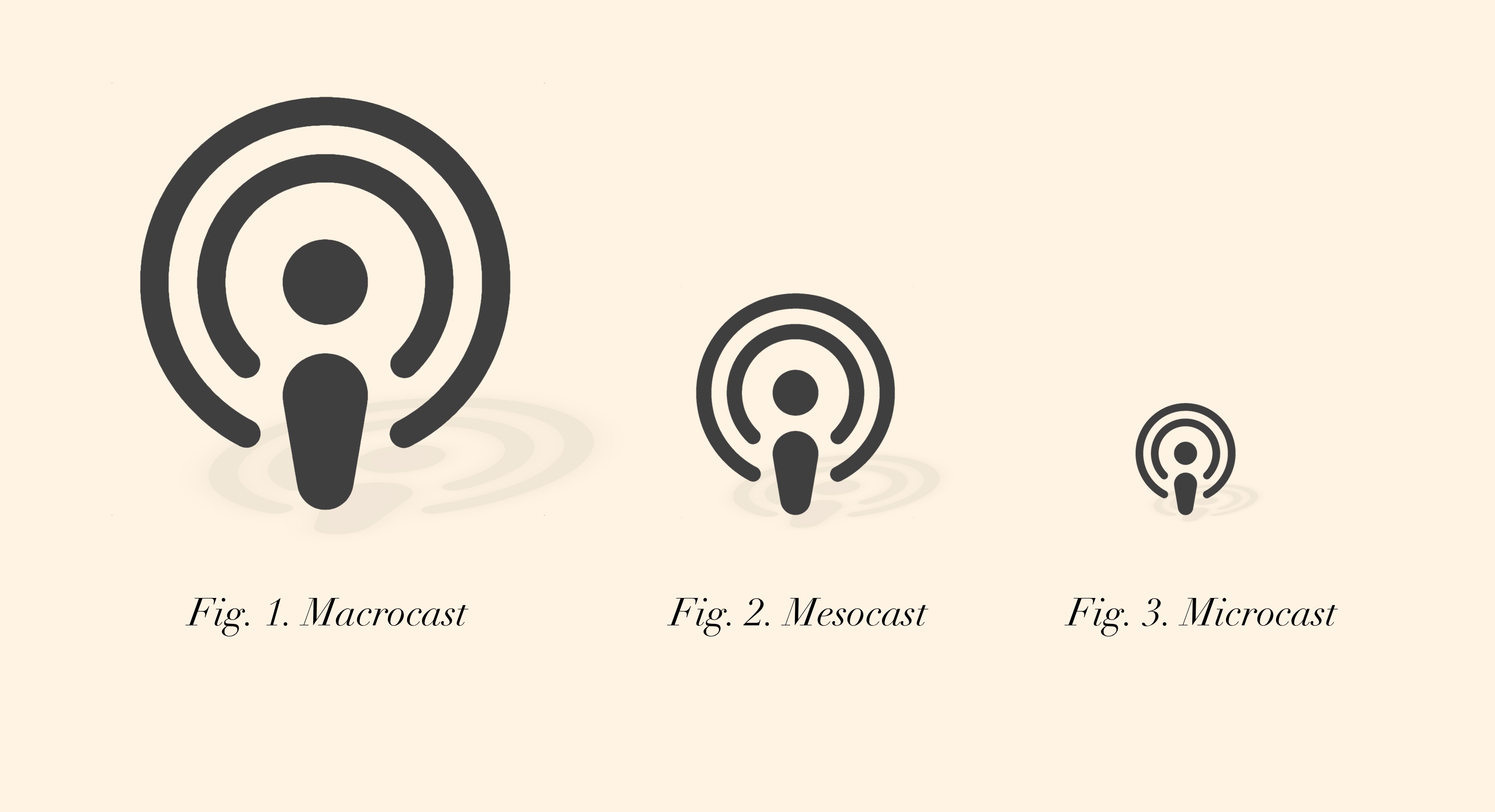

Podcast studios making their episodes shorter for podcast playlists is reminiscent of record labels releasing truncated “radio edits” of songs to make them more suitable for FM airplay. In fact, it’s nothing new for media and entertainment companies to mold their output to fit the technological formats of the time. The podcast playlist format in particular will likely institutionalize the “microcast” — i.e. an episode lasting around five minutes or less — as a mainstream entertainment format, not to mention a production requirement for studios.

While microcasts have been around just as long as the podcast format itself, one could argue that it hasn’t taken off much in the podcast industry. Interestingly, before Spotify-owned Anchor became a full-fledged platform for creating, distributing, and monetizing podcasts, the first version of its app specialized in micro-podcasting, whereby users could post and curate audio snippets lasting up to a few minutes long in a social, Snapchat Stories-style feed. But longer-form podcasts like Serial, Freakonomics Radio, and The Joe Rogan Experience remain the dominant construct for podcasting.

Microcasts could well be a necessity, however, for capturing and retaining attention in the context of a playlist with dozens of other tracks. And in fact, speaking of labels and radio edits, you could say that some of the more proactive proponents of microcasts today come from the music industry.

Last Thursday, Lars Murray — partner at audio podcast production company PopCult Worldwide and former SVP of strategic partnerships at Pandora — penned an op-ed for Variety headlined “What is A Microcast, and Why Do You Need One?” For the past several months, Murray has been working with the musician K.Flay and Interscope Records on a weekly microcast titled What Am I Doing Here?, consisting of roughly 10-minute episodes recorded by the artist wherever she happens to be in the moment.

What’s particularly interesting about this show is that it’s built for smart speakers. “Every Wednesday, there is a new release exclusively on Alexa and Google Home,” describes Murray. “Viewers say ‘Open K.Flay show’ and hear K.Flay talk to them each week. It’s available on YouTube a week later, and we will be releasing the series as a conventional podcast later this year.” For Murray, investing in microcasts is a highly practical matter: As more people listen to music regularly on smart speakers and voice-enabled devices, artists need to think about how they can engage with fans in a way that’s low-friction and doesn’t rely on screens.

Some execs at record labels are also thinking more about how to use microcasts to tell interesting stories that cater specifically to artists’ superfan audiences, especially looking beyond boilerplate promotional fodder.

“In the context of a podcast playlist, the episodes don’t just have to be interviews with the artists,” Tom Mullen, VP of marketing catalog at Atlantic Records, tells me. “You could also interweave a custom, scripted storyline featuring fictional or nonfictional characters throughout the songs. Those are like the spoken interludes you already hear in a lot of albums.” (See Sylvan LaCue’s Apologies in Advance, YBN Cordae’s The Lost Boy, or Kanye West’s The College Dropout.)

This use possibility of microcasting in podcast playlists gives a whole new meaning to the phrase “concept album,” and could potentially give artists the creative freedom to flesh out the storylines in their songs without disrupting the flow of their original, musical project. Indeed, Spotify has already been experimenting with a version of this approach in one-off, multimedia playlist campaigns, including enhanced albums (e.g. for Taylor Swift’s Lover and Post Malone’s Hollywood’s Bleeding) and branded playlist “experiences” (e.g. Billie Eilish Experience, The Beatles Abbey Road Experience and Ken Burns Country Music Experience) that combine audio and visual content into a single playlist. The podcast playlist capability democratizes that native storytelling capability to any artist with a microphone.

It remains to be seen is whether internal teams at Spotify will be invested in creative cross-pollination of music and podcasts as much as external companies are. “The music and podcast teams don’t talk much to each other at Spotify and Apple Music,” Mullen claims. “It’ll be important to watch whether that will change now that podcast playlists are out there.” But the moves and histories of the music divisions in these companies offer their podcast counterparts a ton of value if the latter hopes to make a meaningful dent in the three billion user-generated playlists that already exist on Spotify — and the aforementioned experiments from the likes of Gimlet and Interscope Records have only scratched the surface of what’s possible.

Speaking of Spotify…

Meanwhile, I missed this last week: Reyhan Harmanci is now the deputy head of programming at Gimlet. She was most recently executive editor of First Look Media’s Topic.com property, which was recently restructured, or something.

Lots of change, lots of moving around.

This caught my eye: The New York Times is apparently looking for an audio producer specifically focused on voice assistant platforms. In the job description: “This could mean producing short-form news segments, service journalism programs, or longer audio series.” The relationship between big media brands working as audio publishers and on-demand audio’s on-going infrastructure sprawl remains…a persistent interest.

And while we’re on the subject of job postings: This American Life is looking for an executive editor to “oversee the editorial operations of the program and lead the editorial vision for the show, in collaboration with the show’s Host/Executive Producer Ira Glass.”

Bridging podcasts and book publicity [by Caroline Crampton]. Having to explain what a podcast is in a professional setting might not be a new experience for many Hot Pod readers. There are direct versions of this, where you need potential guests to understand where their interview will be “broadcast” or a family member asks why you spend so much time with headphones on. But there are also indirect versions, which might come up if you work in an industry other than podcasting, you enjoy listening to shows, and you feel like your colleagues could be leveraging audio but aren’t.

This is the situation Lauren Passell found herself in. Until a few years ago, she worked as a social media director at the publishing imprint Little, Brown, mostly focusing on Facebook ads and engagement for authors such as David Sedaris. Outside work hours, though, she spent a lot of time listening to and thinking about podcasts. Although it wasn’t part of her job, she couldn’t help noticing that podcasts didn’t seem to feature much in how publicists thought about how to get attention for new books.

“I noticed that our PR teams weren’t really doing good outreach for podcasts, and honestly it just wasn’t a big deal,” she told me. “No one thought it was important, and I did.”

Occasionally, when she felt there was an overwhelming case for pitching an author to a show she liked, she’d do it herself. “It wasn’t even my job — I loved doing it. I was constantly thinking about it…But even when I would land something, I don’t think anyone really cared.”

Intending to get more professionally involved in the podcast industry, she took a job at WaitWhat, the content incubator behind shows like Masters of Scale and Sincerely, X (which raised $4.5 million in Series A back in February, by the way). She left the role earlier this year to start a company of her own: a publicity agency that would fill the knowledge gap at traditional publishers by building profiles for authors through podcasting. That business has been operating for a few months now and is called Tink.

Passell describes her overall mission as “bridging the gap between publishing and podcasting.” When she first started, she thought that most of her work would come from authors directly. “Basically, I thought at first that authors would just reach out to me individually if they felt like they weren’t getting good podcast coverage. I thought that publishing houses wouldn’t want to work with me because they already have PR departments. But I found the opposite to be true.”

She’s already been hired back by Little, Brown to work on a book campaign and thinks that it’s completely understandable that an already-overstretched publicity team would rather hire in podcast expertise than devote precious internal resources to it. Part of her pitch is her depth of knowledge of the podcasting space — when traditional publishers are trying to place authors on podcasts, she says, they’re mostly hitting Marc Maron’s WTF and not much else.

“But I see the gold in the tier right underneath those [big] shows, and there’s hundreds of thousands of them. And, I mean, these are the shows that want to work with me, and they have great, very large audiences, and they’re very niche, and they have great interviews because there’s no time limit,” she said. The often-discussed intimacy of the relationship between podcaster and listener works very much in an author’s favour, she believes — a longform, discursive interview will contain more reasons for the audience to pick up the book afterwards than a quick news hit on a TV show, say.

Passell’s idea for what the agency would do on Day 1 — basically acting as an interface between already-published authors and podcasts they might guest on — has broadened as she explores the space further. “Someone I’m working with isn’t even an author yet, but she’s a chef with a very interesting story — she’s a Sri Lankan chef who started a food truck in Kentucky and it got super famous. I’m helping her, and I’m hoping that I can get her book someday, and also on some podcasts.” Using podcasts to build a profile before a book deal, it turns out, is a service people want as much as the other way around.

Part of what interested me about Passell’s venture was what it indicates about how traditional publishing houses relate to podcasting. While we’ve seen some experiments with audio-first book deals from Audible and some book publishers (like Macmillan) putting out podcasts based on their titles, it seems like there’s still a lot of unexploited potential in this crossover. For now, the easiest solution while publishing is grappling with change on all fronts (audiobooks, bulk discounting, digital sales, etc.) is just to contract in someone like Passell to extract value from outside opportunities like podcasting while the staff team focus on what are typically deemed as “core” areas.

But what happens when publishers start to wise up and begin to include audio properly in their regular publicity operation — where does that leave Tink?

“I already see a humongous difference in how much [publishers] care about podcasts but I still don’t notice a big uptick in the shows that they’re reaching out to,” Passell said. “I don’t think the problem is that now they just need to get hip to podcasts. I think it’s too overwhelming for them to really do it themselves. I don’t think that is going to change unless they can start hiring people in-house to do this. I think it’s such a humongous world that they’re not going to be able to cover podcasts unless something huge changes.”

The challenge for Passell is to so successfully own the potential connection between authors and podcasts such that, even if a publisher is able to find the salary for a full-time staff podcast publicist, Tink’s offering (in terms of contacts and pitch hit rate) would still be competitive. That’s a big ask for a new small company. It’s a business model that relies on big publishers feeling the pressure of rising costs, but not enough such that it will respond to secondary opportunities quickly.

I feel like we see this pattern around podcasting a lot: basic knowledge gaps and a slow pace of change elsewhere that can be exploited by a new breed of third-party service providers. (See, for instance, all the new “private feed” companies that have appeared recently). In simple terms, if you still have to explain to your boss what a podcast is, you might be able to make some money by selling that answer to others in the same position. But as corporations wise up, the niche that those new companies fill gets smaller and smaller — and survival depends on not only offering an equivalent service, but a better one.