Is Facebook a cesspool of bottom-feeding content? Or is it now the proud leader among platforms in featuring and rewarding high-quality journalism?

Or…both? We’ve got a new breakout of platformitis, as news companies try to figure out their complicated relationships with the dominant digital companies of our day.

As Mark Zuckerberg and News Corp CEO Robert Thomson finished up their conversation at New York City’s Paley Center Friday afternoon, announcing the new Facebook News tab, we can take five big points out of this week in Facebookology. For Zuckerberg, it was the culmination of a week from hell. Just within the past week, he had to juggle: (1) advancing its controversial cryptocurrency, (2) taking down “fake” editorial content, and (3) allowing politicians’ ads with falsehoods to remain. As Thomson said to him in what came across as a fairly softball on-stage talk, “It’s unusual when the amuse-bouche comes at the end of the meal.”

No doubt, the numbers in this deal get attention. News Corp, of course, most likely does the best (see “Rupert always rises to the top,” below), with millions in new revenue. These two- and three-year deals (guaranteed, I understand, even if Facebook nixes the program earlier) will send low millions to some national publishers, maybe half a million a year to a relative few local ones, but only the promise of traffic-generating links to many of the 200 or so other (almost all U.S.) publishers in the initial rollout.

Only the Facebook Live payments are at all comparable in terms of cash payments to publishers for content. And those required lots of original work by publishers; these deals don’t.

And that’s potentially a big milestone here. News publishers will now say that when it comes to paying for content, it’s no longer “whether” but “how much.” (Of course they’d like hundreds of millions or billions to soothe their advertising losses to digital disruption.) They also like doing deals where the dollar amounts are relatively transparent, in which the platforms don’t have to bet on revenue shares of subscriptions or ads sold. This is the big story to watch into the next couple of years.

Zuckerberg is already trying to get out ahead of that in multiple ways. “I don’t pretend that any of these steps will be enough,” he told Thomson, saying Facebook itself couldn’t solve publishers’ problem. But with more than $7 billion in profit, that may be a bit of an overstatement. “Can” may be the wrong verb here.

Curiously, though, Facebook isn’t actually “licensing content.” The experience, as we so far understand it, includes a headline and precis linking back to publishers’ sites, all presented in a stream in Facebook’s new News tab. Isn’t that fair use, what aggregators and platforms have been claiming for two decades?

It’s fairly clear that it’s the currency that motivates the publishers, but what’s the value here for Facebook? It may be more than meets the immediate eye. There’s an engagement value, to be sure; news comes from that simple root “new,” and it drives lots of eyeballs. That’s why Facebook and its platform peers all keep taking new tries at the news biz. Eyeballs are good and lead to monetization.

Then, there’s the softer, behind-the-scenes reasons. “It strikes me that they are front-running the European ‘snippet’ idea,” says one savvy newspaper insider. “We all know that most people are only going to consume the headlines and the snippets, and they’re buying the goodwill of the publishers to participate in the effort.”

Yes, the EU’s taking on of the platforms’ power is starting to inform U.S. behavior. That takes into the political dimension of this agreement, one that somehow got little mention in the Zuckerberg/Thomson conversation.

Call it a shotgun marriage of convenience, perhaps. The news industry needs money — badly. Facebook needs a better story.

It’s under the gun across the U.S. and in Europe. It just agreed to pay a $5 billion fine for its data privacy violations, and it’s just about impossible to even list all the other fronts of questions. And Elizabeth Warren’s break-them-up campaign has sent a new chill through Silicon Valley. All the big platforms, the GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon) named years ago, find themselves in the crosshairs. But given Facebook’s role in the 2016 election and its more complicated “social” nature, Zuckerberg’s company has gotten a greater share of attack.

So this is part PR. Don’t look at the cesspool over there, which we’re cleaning up, says Facebook. Look at all the high-quality news we now proudly pay for. Here’s the new shiny object.

Of course, there could also be this calculation: Publishers may be less inclined to focus on reporting Facebook’s bad side if they see its good one up close and personal. Editors and reporters, of course, would recoil at such a thought, but we can see how Facebook could see it that way — and how it might be right around the edges.

But does Facebook risk marching into new political quicksand Facebook? Remember just three years ago, when Facebook fired its editors who, guess what, curated the news, after Republican House members went ape on them in hearings?

“200 publishers” sounds good. But which 200? The inclusion of Breitbart as a partner (along with the much larger and Murdoch-owned Fox News) has already gotten some on the left fuming. What about preference and placement in the feed? Who decides? Human editors? Algos? Who trains the algos? Round and round we go. It’s a question that a Facebook or any other aggregator can’t answer — unless it’s a journalism company. Which it isn’t.

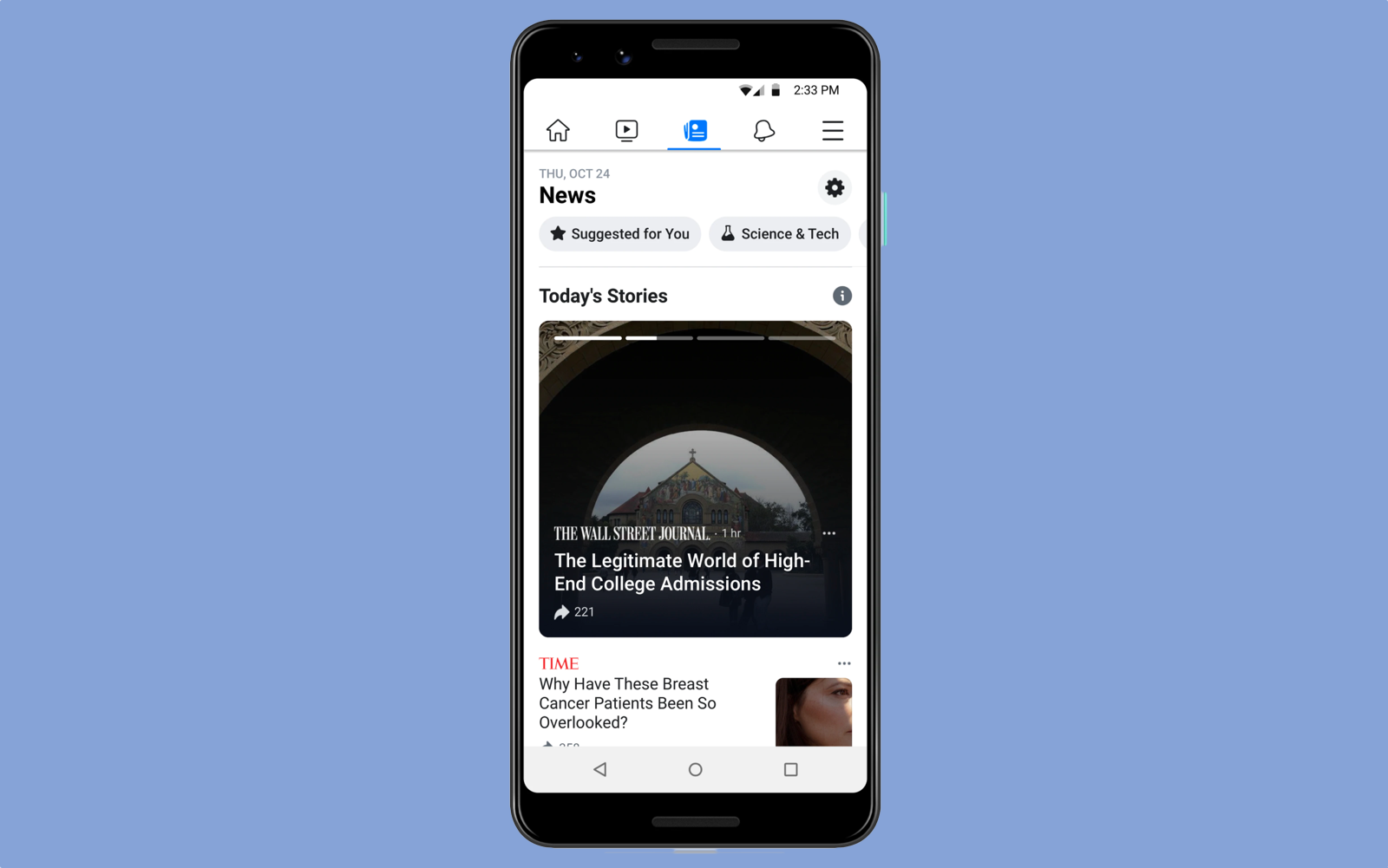

Swipe right? Tap the G icon? Find the new Facebook news tab and touch it? Launch a news app, scroll through Twitter, wait for a news alert? The options for news on our phones can be dizzying. Whose story is this again? How did I get here? Whatever, we think — let’s just read.

That’s the attention battle newly joined by Facebook. Google and Apple both have led with different flavors of news aggregation. While Facebook’s two major competitors here both own most of the hardware, they must still fight their way into readers’ attention. Will the News tab do it, or will it go the way of other Facebook news products, fading away slowly or quickly?

To the degree that any or all of the newest news aggregators — a practice that goes back to Yahoo at the end of the last century — succeed, to what degree are publishers trading their destination businesses for distribution businesses? That’s much more than a monetary question; it’s an existential one. If reader relationship is the gold into the 2020s, what does this new phone-centric aggregation world really portend?

“I do think local news has been hit the hardest by these changes,” Zuckerberg said, acknowledging reality. A number of local providers — McClatchy and broadcaster Graham Holdings among them — are in the new News Tab program. Those are largely in Top 10 markets. “Working with the top 200 news organizations in the world” has been Facebook’s first priority. “Figuring out how to work with all the little ones is going to be critical.”

That’s been true for a while and is universally true among platforms. Executing many small agreements does take a lot of time; integrating more feeds of lesser volumes of content is less economical. Especially for companies who like to start their counting of anything — money, metrics — in the billions. Local content may be high value, but it’s low reach. An alert out of D.C. these days can catch everyone’s attention, but local stories are useful to far fewer. That’s where personalization will come in, hopefully.

Rupert Murdoch and Robert Thomson deserve credit for their early and continued drumbeat calling for platforms and aggregators to pay for the valuable journalistic content they use. And Murdoch, as always, manages to combine wider objectives — like helping lead the industry to get money out of those who have more of it than even he does — with enriching his own company. By most reckoning, his News Corp and Wall Street Journal are receiving the sweetest deal, the greatest payment, from Facebook for this news tab deal. (And the Journal secured one of two top spots in the earlier launched Apple News+.)

Who else are Rupert and Robert talking to, and what may those conversations yield — for them and the industry?