Local news is important. Local newspapers are important, regardless of whether or not you’ve read a word on a dead tree in the past year. As I put it in a piece back in April:

That piece was about a paper from Cleveland State’s Meghan Rubado and the University of Texas’ Jay Jennings that looked specifically at one area of newspaper impact: on local elections. They found that, in communities whose newspaper newsrooms had been cut, local political engagement declined: fewer people ran for mayor, and their races were more likely to feature an incumbent running unopposed or an electoral blowout.What do strong local newspapers do? Well, past research has shown they increase voter turnout, reduce government corruption, make cities financially healthier, make citizens more knowledgable about politics and more likely to engage with local government, force local TV to raise its game, encourage split-ticket (and thus less uniformly partisan) voting, make elected officials more responsive and efficient, and bake the most delicious apple pies. Okay, not that last one.

Local newspapers are basically little machines that spit out healthier democracies. And the best part is that you get to reap the benefits of all those positive outcomes even if you don’t read them yourself. (On behalf of newspaper readers everywhere: You’re welcome.)

That makes sense, right? If the local Daily Planet isn’t reporting on Mayor Johnson’s terrible sewer policy, or his tax hike, or how he yells too much at council meetings, people are less likely to get riled up enough to run against him. (Or how he allegedly extorted a local business for a “Batman Rolex,” or the meth lab at his house, or how he beat up a contractor he thought was sleeping with his wife, or racketeering, or his hotel-room cocaine problem.) People run for office when they see something in government they want to change; a robust local newspaper is pretty good at pointing out problems that need fixing.

That paper produced some useful quantitative data. But what is quantitative data’s best friend, the one who sometimes forgets its wallet or shows up late for things but always has interesting stories to tell? Qualitative data, of course. So Jennings and Rubado are now back with a second paper, titled “Newspaper Decline and the Effect on Local Government Coverage,” that adds some color and personal detail to their first.

Jennings and Rubado interviewed 11 journalists who worked at the shrinking California papers that were part of their last study. “These newspapers all serve metropolitan areas that are relatively small or medium-sized,” they write, and those “interviewed were mostly seasoned reporters and editors of various ranks.”

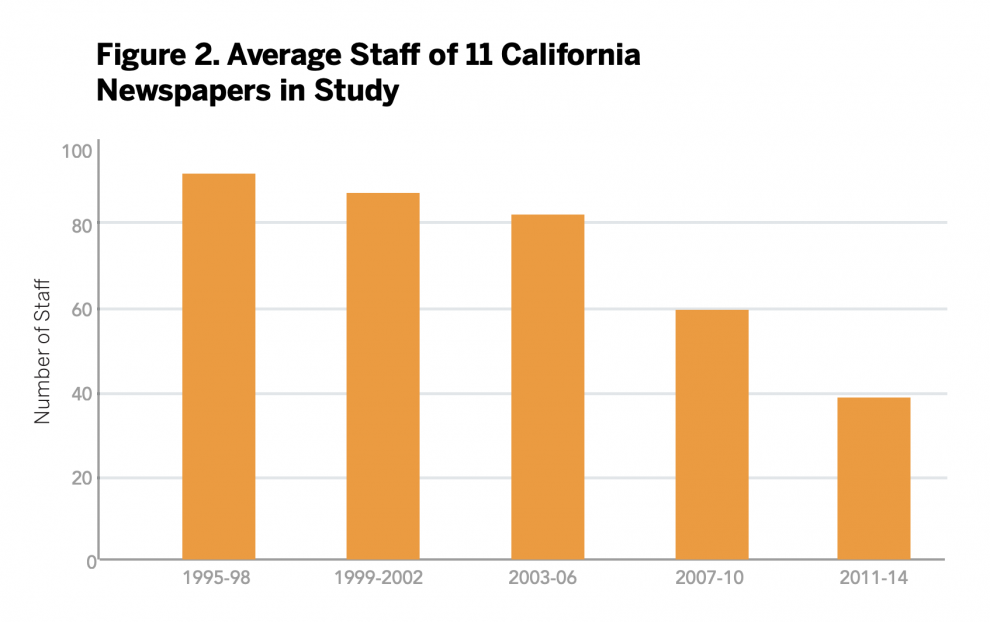

(The papers are the Chico Enterprise-Record, Merced Sun-Star, The Mercury News of San Jose, Santa Maria Times, The Californian of Salinas, The Fresno Bee, The Modesto Bee, The Napa Valley Register, The Record of Stockton, The Sacramento Bee, and The Vallejo Times-Herald. For those keeping score at home, that’s 4 McClatchy papers, 3 MNG/Alden papers, 2 Lee, 1 Gannett, and 1 GateHouse-until-this-week-now-Gannett.)This is what’s happened to the staffing levels in those newsrooms over a 20-year period. It ain’t good. (And note the last line in this chart, like the analysis in their last paper, only goes up to 2014; I can assure you the five years since then have not been a boom time for newspapers.)

Here are a few of the themes that Jennings and Rubado found in their interviews.

As newspapers cut back on coverage — just as when they cut back on distribution — the first things to go are the farthest away from headquarters. Lots of newspapers spent the second half of the 20th century expanding from an urban core to its inner-ring, then outer-ring, then lord-knows-what-ring suburbs. Their retrenchment leaves suburban communities — which have about as many government institutions worth covering as the core city — with a lot less coverage.

In addition to noting changes in the workload of journalists focused on local government and politics, interviewees also linked staffing cuts to the refocusing of news content on the central or main city of the newspaper and a handful of more populous or high-readership neighboring communities. Coverage in outlying suburban or rural areas has been largely dropped or limited to very important breaking news, such as murders or disasters. Several journalists noted that suburban and regional news bureaus had been closed…And readers have noticed. Outlying communities feel ignored, and local residents in more central communities have seen a reduction in coverage too, most interviewees said.

Local reporters shop at the same Kroger you do, send their kids to the same schools as you do, and face the same rush hour traffic you do. That shared experience has helped make local news more trusted by Americans than the stuff that comes out of New York and Washington. But as media consumption becomes more nationalized, the yelling and spinning on cable news colors how people think about their hometown daily.

One reporter said these resident attitudes were further tainted by negative attitudes about national mainstream media outlets. “You know, we’re not CNN; we’re not Fox News; we’re not MSNBC…we’re your neighbors. We want to do good by you, but we can’t do that if you hate us or you think that we’re out to get you or you think that we’re out there with an agenda. We’re not and I don’t — sometimes I just don’t know how to get that across to people who vehemently believe otherwise.”

The structure of local newsrooms has long been a mirror to the structure of local governments. They have courts; we have a courts reporter. They have cops; we have a cops reporter. They have city hall; we have a city hall reporter. There have been good critiques of that system over the years — most notably that those convenient silos don’t always line up with how readers experience the effects of government — but it nonetheless attached reporters to institutions that needs watching. With cutbacks, though, the level of journalistic engagement has broadened — both in geography and in subject area — reducing both the opportunity to gain and the value of expertise.

Reporters who formerly covered a single beat, such as city hall, ended up covering additional beats, like county government and suburban governments, too. One local government reporter who used to focus primarily on city government for the main city in the coverage area noted that declining staffing had caused a piling on of local government coverage responsibilities.“Over the years, I’ve kind of absorbed more and more. So, basically, I cover all of the towns and the county’s government as well. And there’s not very many [reporters], so I also pick up courts reporting, crime reporting, projects, and that sort of thing as they come up.”

Others said beat assignment had been restructured so that, rather than covering a school district or public safety or a single local government, a reporter would cover all of these things and any other news coming out of a particular community.

Newspapers, even in their shrunken state, know that coverage of local government is one of, if not their most important differentiator. The TV stations will get the murders and fires and high school football; the audience for most of the old features section has been lost to national digital competitors. But they’re often the only ones at city hall, and editors have tried to keep that iron core of local news relatively protected.

…some journalists said their newspapers had worked hard to protect local political reporting from the chopping block. While features departments had been gutted or basically eliminated at several of the newspapers in the study, local government and “accountability” reporting remained a priority. Another interviewee, a top editor, said that while beats and coverage strategies had been changed around local government, management strove to dedicate scarce resources to this area.“We have been very careful not to make huge cuts to how we cover local government because if we don’t do this type of coverage, no one else is gonna do it. I am [as] convinced of that today as I was five years ago. And so, our responsibility is to shed light on that, and then tell stories about how local government does impact people’s lives, and then shine a light on things that need to be explained.”

One thing a more robust newsroom allowed was coverage of a particular issue over a broader sweep of its lifespan. Someone dedicated solely to covering city hall, for instance, might hear about a budding legislative idea from a city staffer early on, then see it through as it makes its way (or doesn’t) toward a real bill and, eventually, its impacts on the community. With fewer resources, though, reporters are more likely to report on an issue only when it reaches a public state of prominence — by which time the city’s plans may have already been shaped without much public input. That also limits the newspaper’s ability to influence the civic agenda, for better or worse.

In the past, newspapers devoted much attention to the process of local governance. While, as many of the journalists noted, this focus led to many articles simply reporting the mundane events of council or planning meetings, it also gave the journalists a chance to highlight important policy changes that were in the pipeline at various levels of local government.This coverage provided an agenda-setting role for the newspaper. People who were too busy to attend every council meeting could instead count on their local paper to let them know if there were important changes coming, giving them a chance to get involved in the process while the proposed policy was still in its infancy.

What has happened in recent years, due to staffing cuts and a focus on article-level readership metrics (clicks), is that local government coverage has focused more on happenings within local government that will immediately or have already begun affecting citizens. While this shift may seem subtle, we see this as an important and potentially dangerous change in local government coverage, as do many of the journalists we spoke to. The press, instead of influencing the interactions between representatives and the represented, are simply covering the effects the representatives are having on those they represent.

That is perhaps the most consistent theme in this paper overall: that a smaller newsroom is inherently more reactive and less proactive. With less time to invest in reporting that might not turn into a story, journalists are left catching onto issues too late, too readily manipulated by communications staffers who can mete out details at their own desired pace.

As one journalist put it in an interview:

Now, the newspaper reacts to news in the community and what people are doing. So, instead of setting an agenda for what the community is talking about, by necessity the newspaper would have to write about what people are talking about after the fact. That’s the big difference. We just didn’t have enough people to set the agenda…

People wouldn’t get advance notice in the newspaper about a subdivision going on over their back-fence line until it got to that final level of approval at the city council level. That’s a real shame, if you’re an active citizen trying to stay involved in what’s going on in your city. You would not be able to get it from the newspaper. You would have to pay attention to planning commission agendas and architectural review board agendas and all these things that nobody in the world except for a newspaper reporter pays any attention to.

All of that makes the local newspaper less useful for even the most civic-minded of readers — the ones newspapers increasingly count on to pay up for digital access.

The loss of reporters’ time here is, Jennings and Rubado point out, twofold. First, fewer journalists mean more output required from each one. And second, the shift to digital publishing has meant that the window between news happening and news being published — a critical time in which a reporter can make some extra calls, check some extra facts, add some more context — has shrunk.

All of that contributes to what the authors found in their first paper — a damaged newspaper creates a damaged civic life. “People will always stick with what they’re familiar with, what’s comfortable, what is working,” one reporter said. “And if you don’t have a newspaper staff who points out when things aren’t working, there is no impetus behind trying to put somebody new in, right?”

You can find the full paper — which was backed by the Annette Strauss Institute for Civic Life at The University of Texas and the Knight Foundation — here.