Many journalists are put in some degree of danger because of their work — from the most extreme examples (the Capital Gazette shooting, the bomb that was mailed to CNN, the 25 journalists killed for their work around the world in 2019) to more limited cases.

But this week’s controversy involving Washington Post reporter Felicia Sonmez (who was subjected to death and rape threats after tweeting an article about Kobe Bryant’s rape accusation) only highlighted what we already know to be true: women, and particularly women of color, bear the brunt of harassment, both online and in person.

According to a 2019 survey of 115 of female and gender-nonconforming journalists by the Committee to Protect Journalists, 70 percent experienced safety issues on the job while 90 percent indicated online harassment as the biggest threat to journalist safety.

Because journalists are often required to have an online presence, Kat Duncan, the interim director of innovation at the Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri, thought it was only fitting to design an app that offers support and resources to female journalists in dangerous situations.

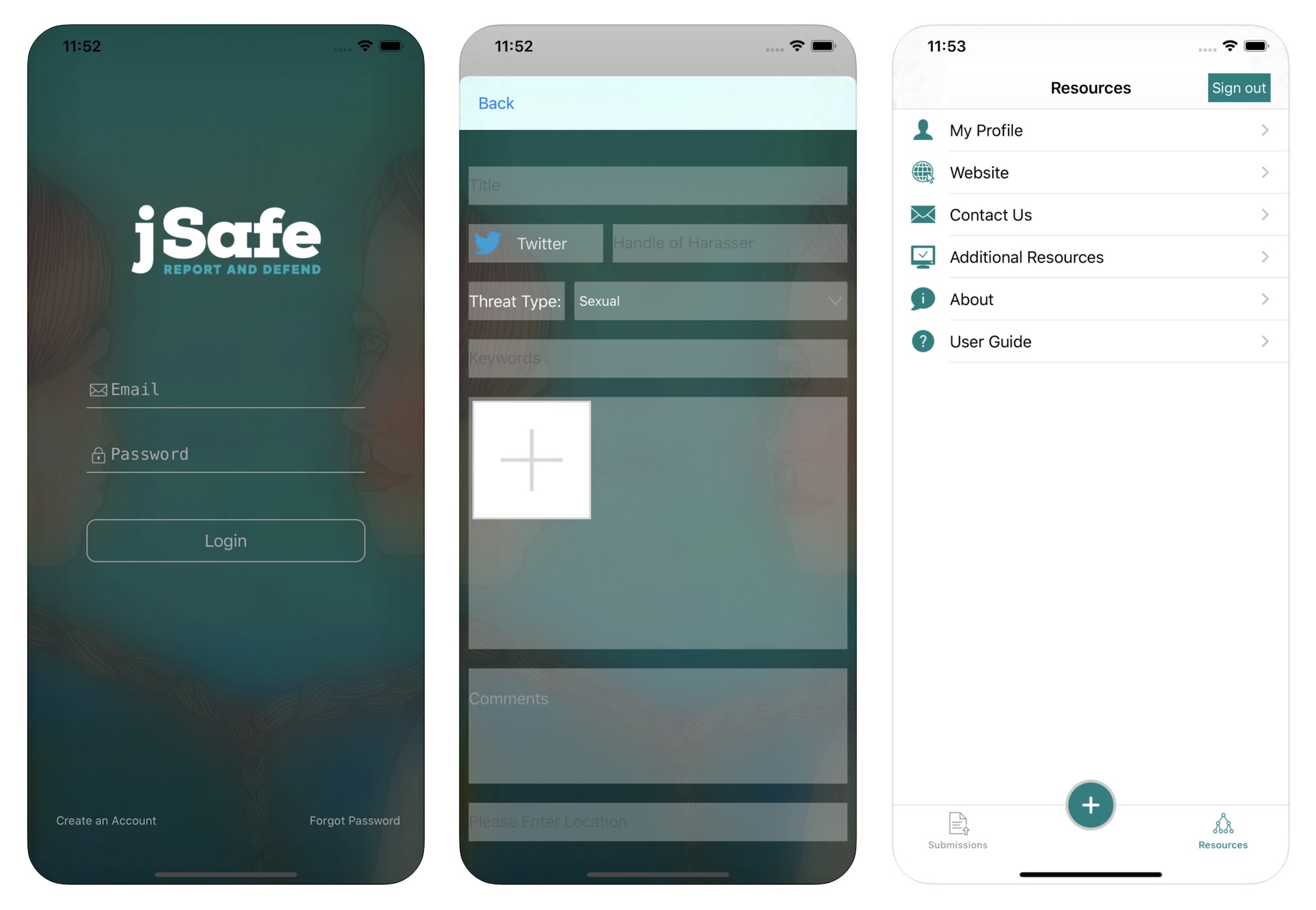

Cue JSafe.

Duncan said the idea came out of the Women in Journalism workshop she runs at Mizzou every year. “I had a lot of closed-door discussions about safety, online safety, trolls, and what everyone goes through. The consensus was that it was getting more intense online with bots and trolls,” Duncan said. “The women I was talking to said they wanted a way to log what was happening in a safe way, so that if something were to happen to them, they had proof somewhere.”

She partnered with Mizzou’s College of Engineering to build the app but knew someone else had to run it full-time once it launched. She posted in Riotrrrs Of Journalism, a private Facebook group for women in journalism, to see if anyone would be willing to manage the app. The Coalition of Women in Journalism reached out and said they already offer similar support services and offered to take it over once it launches.

The app is pretty basic. Users can add an incident, include photos and videos, and add a location tag. They can also add a hashtag so that attacks can be sorted. If they mark an incident as “urgent,” it’ll alert the Coalition to follow up with the journalist about resources (about mental health services, attorney information, law enforcement contacts, etc) and next steps. Duncan said the Coalition will also track certain Twitter handles and Facebook accounts so that they can work with the social media platforms to shut down abusive accounts.

Harassment “has always been an issue for women in the field,” Duncan said. “I was a female photographer on the sidelines of football games. You could leave it behind when you got home but now, journalists have to be on Facebook and Twitter and they’re just getting bombarded with trolls. We’d love to help them in these situations.”

Duncan is now looking for 50 beta testers to get feedback on the app and launch it later this spring. You can sign up here.

One comment:

Others say that after 30years of pink branding, everyone is aware of breast cancer andraising awareness further isn t really going to help cure thedisease cialis prescription

Trackbacks:

Leave a comment