Editor’s note: This morning, The New York Times published a photo essay headlined “The Great Empty”: a collection of “images of once-bustling public plazas, beaches, fairgrounds, restaurants, movie theaters, tourist meccas and train stations” that have been drained of human occupants by the coronavirus. In this essay, Cherine Fahd and Sara Oscar examine the role these photos of empty public spaces fit into the history of art and photojournalism.

Over the last few weeks, photographs in the news and on social media have documented our behavior in response to COVID-19. Panic buying of pasta, rice and, surprisingly, toilet paper is represented in empty shelf after empty shelf.

That’s not all that is empty.

Images of empty public spaces — from the streets of Ginza, to soccer stadiums, to the Venice canals, to lone masked travelers on buses, trains, and trams — evoke a sense of apocalyptic films and the end of days.

Photographs of empty public spaces are increasingly filling our news feeds, documenting our response to a worldwide pandemic. While these pictures point to a frightening situation, we can’t help being drawn into the otherworldly and unfamiliar scenes. They make us stop, look, and linger as we try to comprehend what these places without people are saying.

Our attraction to images of the world without us reveals a collective fascination for the apocalypse or, perhaps, extinction.

Take the Instagram feed Beautiful Abandoned Places and its 1.2 million followers. These photographs show buildings in ruins or overgrown with weeds; old tourist sites now empty.

The images are ruin porn: when we take voyeuristic pleasure or delight in the sight of architectural decay or dilapidation. The appeal comes from looking at a scene that could cause discomfort (or estrangement, or isolation) but doesn’t. The viewer is looking at a representation of the scene, not the scene itself, from a position of far-off comfort.

But another definition of ruin porn, a moral definition, is gaining pleasure from someone else’s failure, as seen through these architectural ruins. Morally compromised as outsiders, we aestheticize a picture of another’s decline while looking away from factors that contribute to crisis.

The images in our current news feeds — despite what they say about coronavirus — offer similarly compelling visuals. We take delight in the formal composition of these images, which fall into tropes of the photographic picturesque.

The absence of people provides us with the ability to see into the distance with endless visual perspective. We feel as though we are alone in the landscape, a heroic adventurer.

Why is our absence from the world so fascinating to view in photographs?

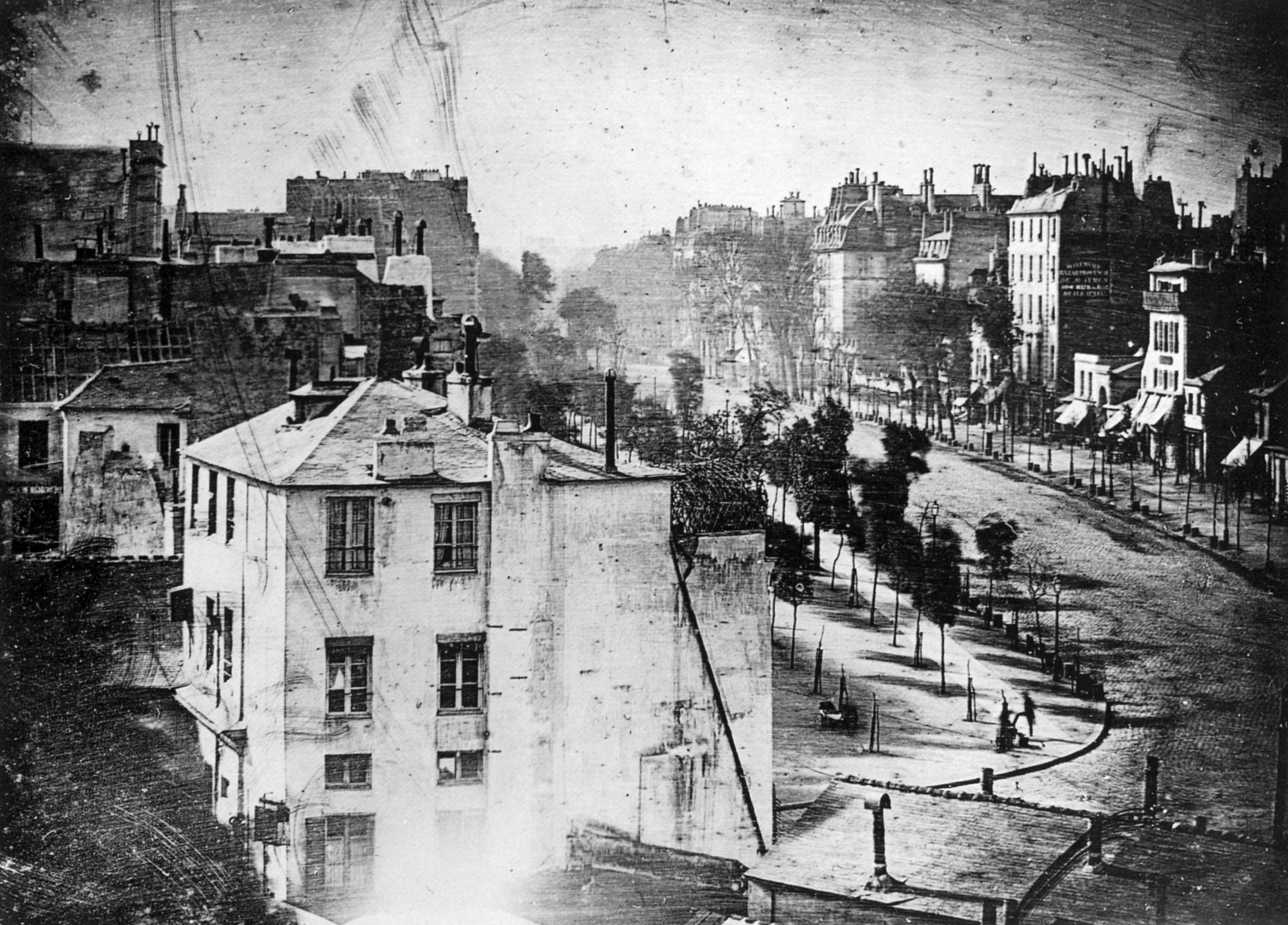

In the early era of photography, anything moving would be rendered invisible, while architecture (or a corpse) was the perfect still subject. Take for instance Daguerre’s 1839 photograph of the Boulevard du Temple, Paris, a bustling city street.

In this photograph, the street appears empty — with the exception of two figures who have stood still long enough to be captured by the exposure time required to portray the scene.

Photographs have always provided us with an alternative view of the world without us.

Contemporary fine art photographer Candida Höfer has made a successful career out of photographing large-scale empty spaces like public libraries, museums, theatres and cathedrals. Thomas Struth’s empty street photographs make German cities look like ghost towns.

These artists demonstrate a longstanding fascination with photographing architecture devoid of human subjects.

This fascination may be due to what architectural historian Anthony Vidler described as “the architectural uncanny.” Abandoned and deserted spaces, he said, make our familiar spaces become unfamiliar. For Vidler, this estrangement from space hinges on visual representation, such as in photography. These photographs of empty public spaces capture a departure from our everyday and instead visualize this uncanniness: an alternative reality emptied of our presence.

The uncanny, wrote Vidler:

would be sinister, disturbing, suspect, strange; it would be characterized better as “dread” than terror, deriving its force from its very inexplicability, its sense of lurking unease, rather than from any clearly defined source of fear — an uncomfortable sense of haunting rather than a present apparition.

While we hide away and quarantine ourselves indoors, the world outside is captured in the collective imaginary as eerily without us. What we thought we knew of public spaces is instead evoking the sensation of being alone in a haunted house. In images where we expect to see hundreds or thousands of people, we find instead a few lonely figures presented to us by a single observer: the camera.

Pictorial urban life emptied of its citizens produces an assortment of emotional responses: estrangement, social alienation, melancholy.

The Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico captured this in his 1913 painting Melancholy of a Beautiful Day where an ominous figure stands alone in an empty town street accompanied only by his shadow and a Roman statue in the distance.

Made over a century ago, de Chirico’s painting surprisingly resonates with the photographs we are seeing in the news today. While it offers a historical example of the surrealist fascination with psychological dream states, it is also prescient of our current reality.

The images being captured by news photographers point to our fear of the pandemic and, fundamentally, of each other. They expose how swiftly we can become estranged from our everyday lives, how our surroundings can suddenly become something other — something fragile and tenuous.

The empty shelves, the empty restaurants, the grounded planes, the empty airports, the depopulated Mecca without worshipers, Trafalgar Square without tourists: these are all signals of the slowing of progress.

Photography is so good at capturing this because it is an unmediated mechanical eye that confronts our all-too-human eye. In these instances, the camera is able to be where we cannot be. The mechanical eye is further exaggerated in the photographs which provide us with a distinctly nonhuman view of open, empty spaces. Drone images give us an aerial perspective not readily available to the human eye. When viewed in the context of a global health crisis, there is no mistaking that we are — somewhat strangely — bearing witness to our own erasure.

We are accustomed to seeing images of crisis represented by fires, floods, bombs, warfare. The photographs we see as a result of COVID-19 are an emptying out and a slowing down. This is a different sort of crisis, one mirrored in the uncertainty and slowing down of our financial markets and the need for government stimulus packages. As the cultural historian Frederic Jameson said, “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.”

Perhaps this is precisely what these photographs are showing us: how the pandemic paradigm of “social distancing,” which isolates us physically from each other, disrupts and stops our lifestyles.

The pausing or ending of our gathering in public — in airports and hotels, at tourist sites and sporting matches, in shopping malls, museums, and bars — signals a rupture to the flow of everyday life.

Photographs of empty public spaces unmask the illusion that we are integral to existence. Even without a camera operator, optical technology will linger on and capture scenes of the world without presence. Who can say whether that operator is human, or nonhuman, like a satellite from outer space that is still programmed to picture our buildings even if we aren’t in them?

Cherine Fahd and Sara Oscar are both artists, photographers, and lecturers at the School of Design of the University of Technology Sydney, where Fahd is also director of photography. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.![]()