With schools closed because of the coronavirus pandemic, lots of people are adjusting to having their kids at home all day long. Radio Ambulante’s Daniel Alarcón has been threading his parenting-in-quarantine experiences on Twitter:

Day 5 pic.twitter.com/8lPMNNCTQA

— Daniel Alarcón (@DanielGAlarcon) March 21, 2020

The 19th’s Emily Ramshaw is finding new ways to bond with her daughter:

Social distancing strategy. Thanks, @yogawithadriene! pic.twitter.com/CxsN6tG1VV

— Emily Ramshaw (@eramshaw) March 14, 2020

Sports writer Shireen Ahmed and her kids are figuring out their co-working space:

My almost 20 yo son started his summer job and was in a meeting. He's so professional and smart that it's s hard for me to contain my pride.

After he said "Have a good day!",

I kissed his head while exclaiming: "Aren't you a diligent busy bee?"Boss was still on the call.

— Shireen Ahmed (@_shireenahmed_) April 21, 2020

Beyond the day-to-day arrangements, one big issue for parents of kids of all ages is how to talk with them about the pandemic madness that’s keeping them homebound. They can be hard conversations to have. Over the past few weeks, a number of different news outlets have been producing projects aimed at to inform kids without scaring them — as well as giving parents some peace of mind about the information their kids are consuming.

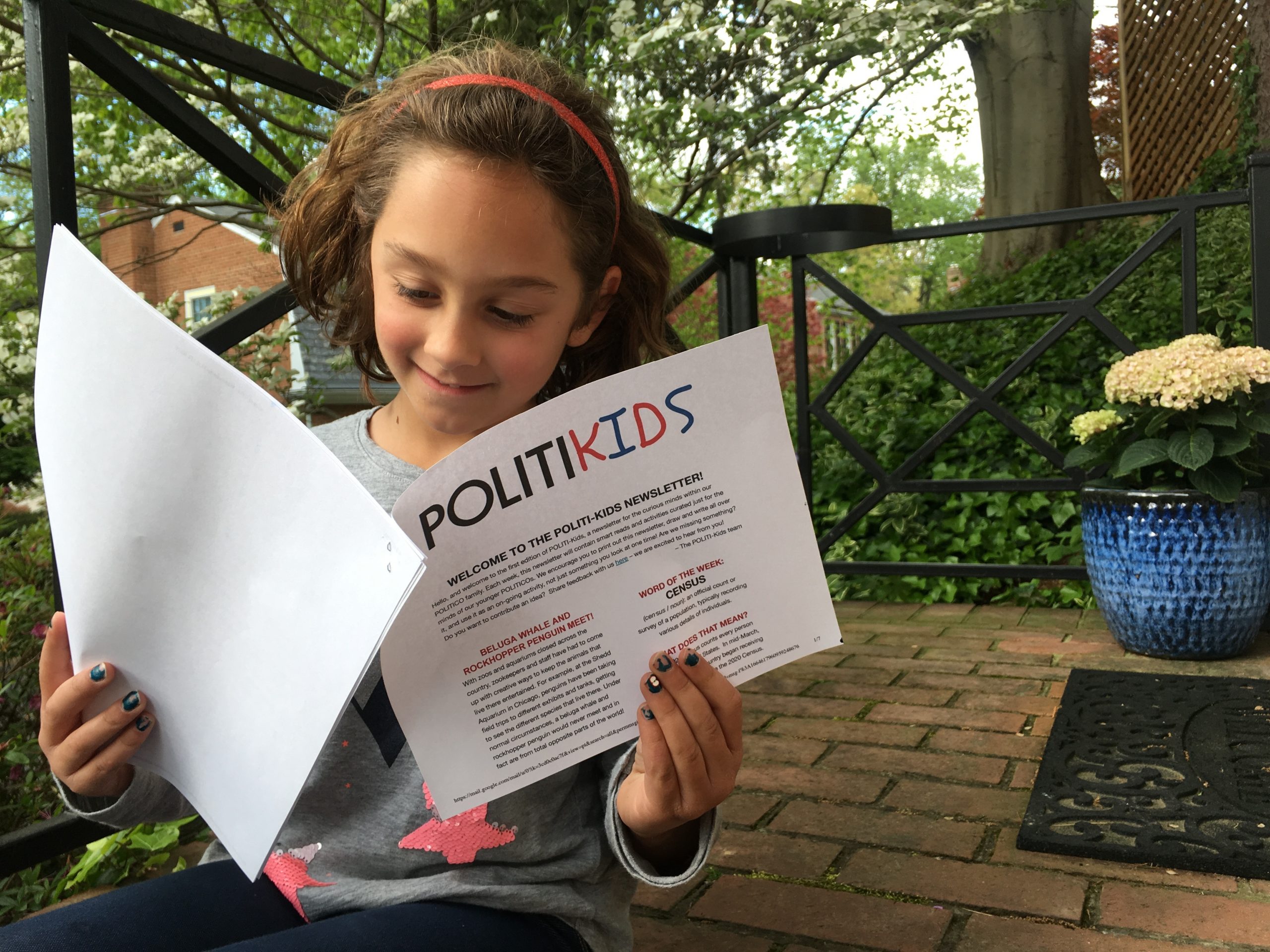

At Politico, business operations specialist Alexa Velickovich and editorial operations project manager Aloise Phelps teamed up to produce POLITI-Kids, an internal weekly newsletter for the children of Politico employees.

“We both support people that have young kids, and we’ve kind of seen firsthand how challenging it can be to juggle, work life with home,” Phelps said. “We thought now is the best time to keep the kids occupied a little bit but also be inquisitive and teachable.”

POLITI-Kids isn’t a product of the newsroom, and for now, there aren’t any plans to expand it. Phelps and Velickovich said they were overwhelmed by interest in the newsletter from folks outside of Politico, so they made the subscription link public.

I’m sorry @politico is doing a POLITI-kids newsletter and i am shook. This is 100% exactly what I would have wanted as an elementary schooler I shit you not, I would have hoarded these. pic.twitter.com/sYT1LIaQLU

— Natalie Fertig (@natsfert) April 10, 2020

This week’s recipe from POLITICO’s kid-friendly newsletter looks fun. I’ll make the snickerdoodles if you make these for the office, @jackshafer pic.twitter.com/Glq9Hu4X6z

— Gabby Orr (@GabbyOrr_) April 17, 2020

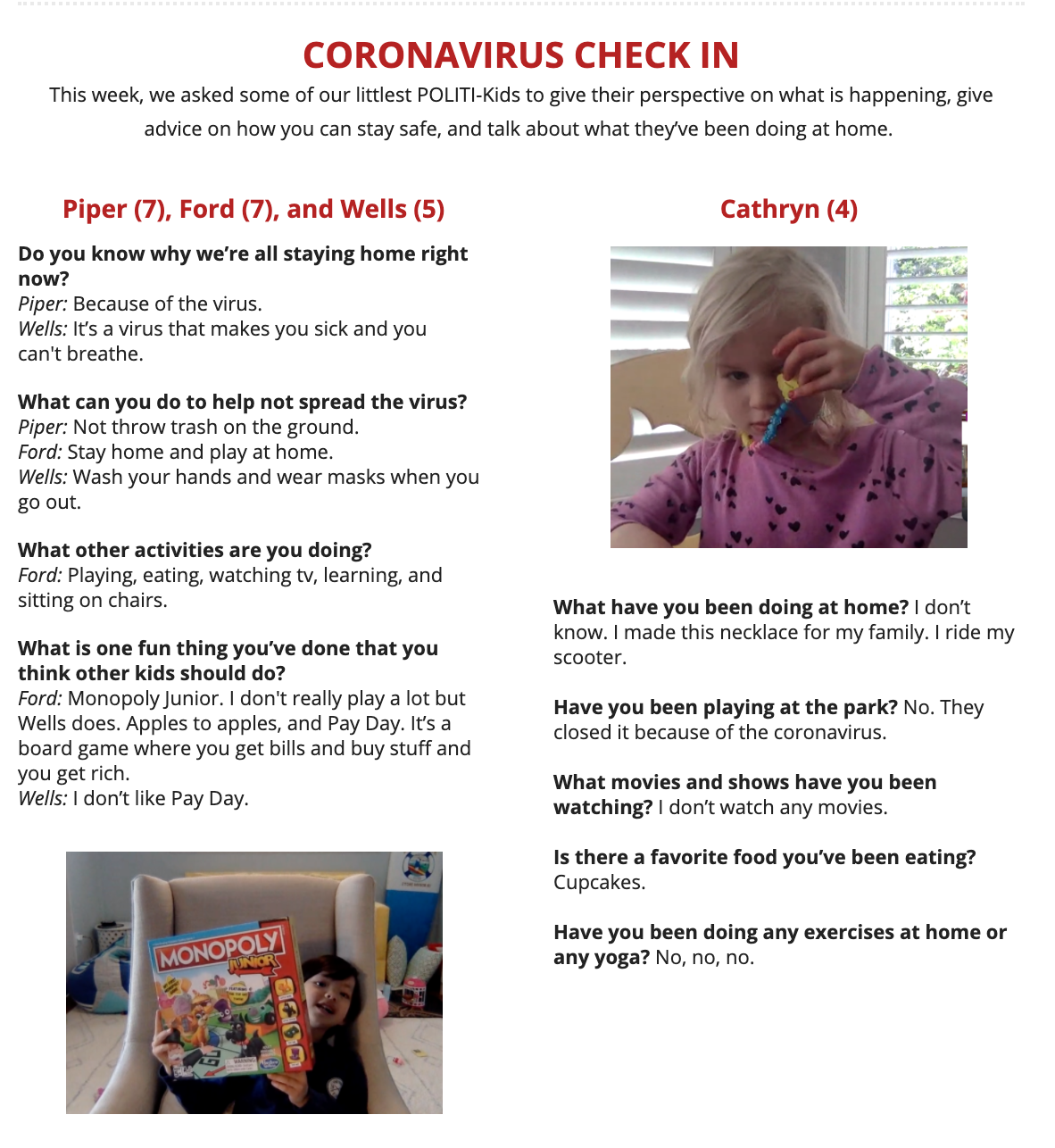

Each edition includes a top news story (a condensed version of the week’s biggest political story), plus key definitions and guided reading questions. There are also photos, coloring pages, puzzles, recipes, and a joke of the week. (What did the paper say to the pencil? You have a good point.)

It even has a check-in with their readers:

In your @nytimes this Sunday, 4/26, the April issue of The New York Times for Kids! pic.twitter.com/8l10agp0nJ

— Caitlin Roper (@caitlinroper) April 21, 2020

Kids section editor Amber Williams said this was the first edition of the section to be produced remotely, which presented a number of logistical challenges. In addition to not being able to approve pages with printed proofs, the Kids section also had to omit its opinion section. (Usually, Williams visits a fourth grade class in a different city and teaches them about the difference between news and opinion, then have them write their own opinion pieces to be published in the section.)

That couldn’t be pulled together for the April issue — schools were still figuring out Zoom — but the issue is unique in other ways.

“This issue has the most kids voices we’ve ever had,” Williams said. “They dominate this issue, and it’s largely because when I was putting the lineup together, it became so clear that, since things change so quickly day-to-day and we never know what’s happening next, the issue was going to be less explainers and analysis and more reflective and hearing about as many experiences as possible, and letting the conversation be guided by kids and readers, and a conversation with each other.”

Williams said the most important part of this issue, as with the others, is making sure the writing never talks down to kids. The front page is titled “Reminder: You Are Not Alone!” and shows an illustration of two kids looking out of their window and seeing another kid across the street. The issue features smart stories like tips for making school-at-home work, the science behind how soap disinfects your hands, and a sidebar on what’s happening with the U.S. presidential election.

From the home-learning story:

Both Tristan and Cora have noticed that the switch to home learning has given them more independence. For Tristan, it was “pretty cool” to learn that he could handle lessons on his own “without teachers lecturing me,” he says. And Cora says she appreciates being able to schedule her own time: “If in the morning, I’m not in the mood for writing,” she says, “I can switch it with math.”

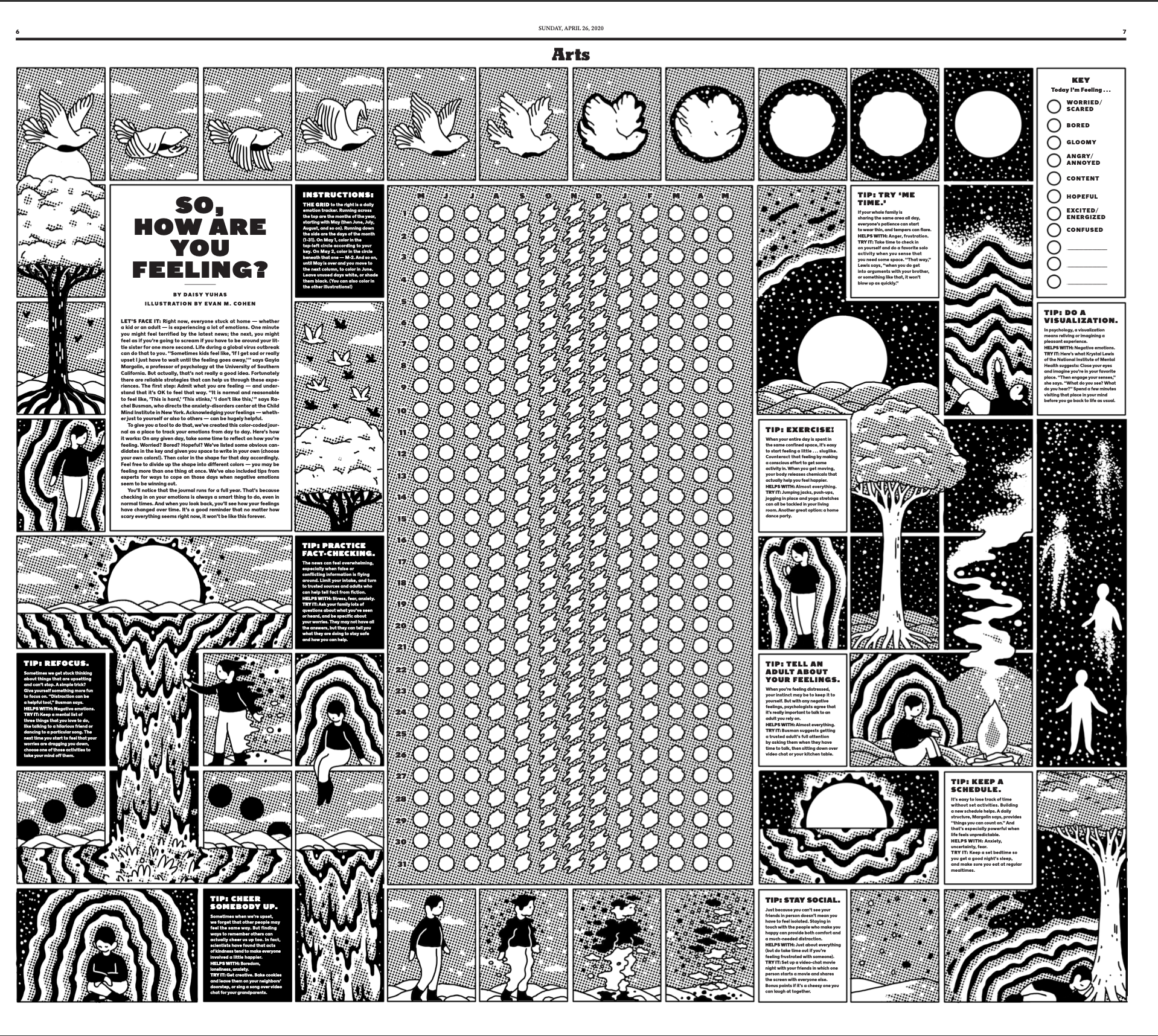

NYT for Kids is often stuffed with activities like board games, quizzes, and photo essays, but Williams said validating the reader’s emotional wellbeing was particularly important.

“The center spread is actually based off of an emotion tracker and the idea of how this is a crazy time,” Williams said. “One way to find some common ground it is to track your emotions and see how they change over time. And that’s surrounded by advice from experts, psychologists, and behavioral therapists about what we know based on research about what can make us feel better.”

(If only the adult version of The Times had this, too.)

For Chris Colin, a freelance journalist in San Francisco, the new reality was brought to the forefront while being sheltered in place with his own children. That led him to start Six Feet of Separation, a newspaper for kids in his neighborhood of Bernal Heights.

“These kids were just bored and just I was like: Oh my god, are we going to be just depositing them in front of Netflix for the next however many months?” Colin said. “So I just fired off an email to a few friends and neighbors asking if they would invite their children to submit articles about what was going to be to a local newspaper that I that I was going to start that was going to be by kids and for kids, rooted in this strange new reality that we were embarking on.”

The result is a 30-page digital newspaper where everything, from the stories, the advice columns, the horoscopes and the cartoons, are all produced by kids. Colin works with the kids on their writing and pushes them, but there are no bad ideas.

“I said right away was that my editorial policy is ‘yes,'” Colin said. “I’m from a world where you have to untangle the competitive world of grownup journalism. I thought as long as we’re ripping up a lot of the playbook here in the corona era, might as well rip up that rule, which I see no reason to expose kids to. I’ve painted myself into a fun little corner where I now find a way to publish everyone.”

The San Francisco Chronicle first wrote about it last month and it caught the attention of Dan Rather:

A virtual newspaper for our troubled. times. That it is being written by the children who will lead us to a better future gives hope. I love this idea. A tip of the Stetson to all involved. https://t.co/ZFYZDmxEqx

— Dan Rather (@DanRather) March 29, 2020

As with the Times, Colin says he felt compelled to give kids space to process their feelings. “Kids are going through something profound and hard to describe right now,” he said. “Grownups, we have our various coping mechanisms and ways of processing this strange new reality. We have our Zoom calls and our alcohol and our memes. The kids don’t have those tools and they don’t always have the ability to understand this historic thing that’s unfolding in real time. I’m a writer and my orientation is to figure things out by writing them down and by reporting. So my move was to invite kids to do the same.”

All of these products encourage reading and critical thinking among kids, but also required the journalists to flex different muscles in making the stories digestible and accessible. Lester Holt, anchor of the NBC Nightly News since 2015, now also hosts the Nightly News: Kids Edition, a digital newscast on Tuesdays and Thursdays that lets kids ask the questions that NBC’s journalists will report on.

Holt told me the idea for the show came from senior producer Brad Jaffy and that the team latched onto it immediately. While anchoring the regular Nightly News, Holt said he often thought about the kids who were watching at home with their parents as he reported death tolls and confusion over what the virus can or can’t do.

“I think our program is a port in the storm,” he said. “We get tossed by the waves of opinion and blogs and social media all day long, and we hear this and that. And I’ve always felt that we were a broadcast where you could pull into a safe port and for 30 minutes every night. We walk through the day, it’s ‘what we know, what we don’t know,’ and put in some perspective, so that we can all come away with a sense of where the world is today. I think we’re fulfilling that same role, but at the same time we’re replaying the story of our lifetimes. At this point, you know it’s an important story, we all have questions, and we want to know when it’s going to be over.”

The show’s format is looser than the regular Nightly News: it’s online only, twice a week, and anywhere from eight to 15 minutes long. But it requires Holt and the team to find language that cuts through the noise.

“This was an opportunity for us to really try to put this stuff in perspective for kids and acknowledge that this is tough for even the adults,” Holt said. “We thought this would be a great opportunity for us to leverage our reporting strength, but try to gear something a little bit more toward the questions that kids might be asking and try to help them through this.”

Holt said it’s important not to dwell on some of the more grim aspects of the story while also acknowledging that this is a serious issue with widespread impact. Kids submit video questions from around the country — and those questions can be tough.

“One of the questions was about why they can’t see their grandparents, and that’s a that’s a difficult one — because you don’t want to give the notion that if you visit your grandparents, something awful is going to happen,” Holt said. “Although we know that there is a risk, and that’s why you may not be able to right now see your grandparents, that’s when we had to make sure the language was careful in how we explained it. But it’s an important topic, and they need to know there’s a reason why older people are a little more at risk right now, and that it’s a good idea if we don’t spend too much time face-to-face with them.”

The big news event that shook up my life as a child was 9/11. I was six years old, in the second grade in Queens, New York. The only information I had access to was whatever CNN, my teacher, and my parents told me. I didn’t come to understand how that event had affected me until years later.

In the nearly 20 years since then, children’s access to information has grown enormously. With all of the efforts being made to keep them informed about coronavirus, let’s hope that, when this is all over, they won’t just be okay — they’ll be smarter and more engaged with the world around them.