Editor’s note: Longtime Nieman Lab readers know the bylines of Mark Coddington and Seth Lewis. Mark wrote the weekly This Week in Review column for us from 2010 to 2014; Seth’s written for us off and on since 2010. Together they’ve launched a new monthly newsletter on recent academic research around journalism. It’s called RQ1 and we’re happy to bring each issue to you here at Nieman Lab.

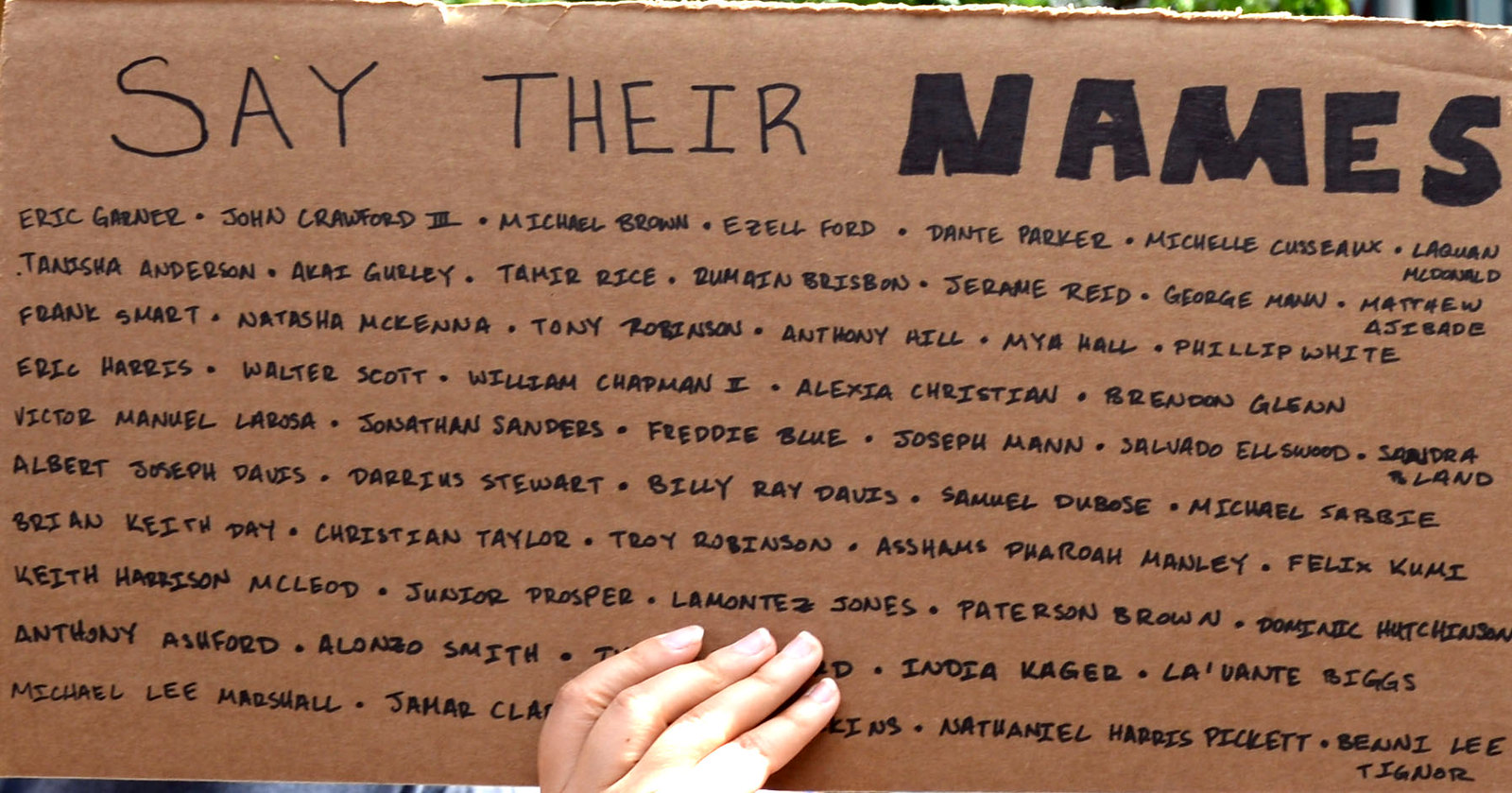

We are deeply saddened by recent episodes of murder and violence against black men and women perpetuated by police, reflecting enduring injustices against the African-American community that have been at the center of recent protests in cities large and small around the United States and beyond. In light of these events, we’d like to begin this month’s newsletter by pointing to a new book that is particularly timely and illuminating, one that adds an historical dimension to understanding current issues around race, journalism, and technology.

Last month, Oxford University Press published Allissa V. Richardson‘s Bearing Witness While Black: African Americans, Smartphones, and the New Protest #Journalism. The book introduces the concept of “black witnessing” by exploring the Black Lives Matter movement through the eyes of activists who documented it through cellphones and Twitter, and by connecting BLM to a longer history of African-Americans using news in combination with activism as a vehicle for confronting racism.

If BLM has benefited from a “perfect storm of smartphones, social media, and social justice” empowering activists to expose police brutality that disproportionately affects blacks, the movement also can be seen as part of a broader tradition of media-infused witnessing. Richardson, who is known for her work in mobile and citizen journalism and as an educator who has trained journalists in the U.S. and Africa to report using only mobile technologies, draws together three overlapping phases of terror against African-Americans: slavery, lynching, and police violence. She shows how “storytellers during each period documented its atrocities through journalism,” from 1700s slave narratives that helped inspire the Abolitionist movement, to 1800s black newspapers that furthered the anti-lynching and Civil Rights movements, to today’s use of smartphones to hold police to account.

But even while images and videos can serve a vital role in catalyzing social change, as they have done recently, they also need to be handled with care, Richardson argues. “I call for Americans to stop viewing footage of black people dying so casually,” she said last week in writing about her new book. “Instead, cellphone videos of vigilante violence and fatal police encounters should be viewed like lynching photographs — with solemn reserve and careful circulation.” That is, just as previous generations of activists used graphic images briefly and in the particular context of their social justice activism, “airing the tragic footage on TV, in auto-play videos on websites and social media is no longer serving its social justice purpose, and is now simply exploitative.”

(Elsewhere, you can find a special collection of studies about news coverage of protests that has just been published by The International Journal of Press/Politics; all of the studies are available with free access for the next two weeks.)

Read with reflection, Richardson’s book and many related accounts — such as these studies on Black Lives Matter and journalism published in the past several years — should help us all become more aware about previously unquestioned assumptions, blind spots, or misunderstandings that we may have personally or that may be evident collectively in our society surrounding race, inequalities, and media representations.

Here are some other studies that caught our eye this month:

Do online, offline, and multiplatform journalists differ in their professional principles and practices? Findings from a multinational study. By Imke Henkel, Neil Thurman, Judith Möller, and Damian Trilling, in Journalism Studies.

For a couple of decades, journalists and academics have wrestled with the question of whether online journalists are a different breed from their offline counterparts — and if so, how. Henkel and her colleagues used the massive international survey of journalists called Worlds of Journalism to provide us with the most comprehensive answer to that question yet.

They looked at four areas of journalistic values — public service, objectivity, autonomy, and ethics — and found that online and offline journalists largely hold the same professional ideology. There were a few key differences within that picture: Journalists at digital-native news organizations found the watchdog role less important, but felt more freedom to select and frame news stories. Journalists at online branches of legacy news organizations also described an entertainment role as more prominent and saw influencing public opinion as less important than their offline counterparts did.

A first-person promise? A content-analysis of immersive journalistic productions. By Kiki de Bruin, Yael de Haan, Sanne Kruikemeier, Sophie Lecheler, and Nele Goutier, in Journalism.

Immersive journalism — often associated with virtual reality, augmented reality, and 360-degree video — has attracted a lot of enthusiasm in the industry and the academy, but this study highlights the sizable gap between the promise of this form of news and its actual practice. De Bruin and her colleagues identified the unifying elements of immersive journalism as immersive technology, immersive narratives, the possibility of user interaction, and sense of presence. They then looked at about 200 immersive journalism examples from around the world to find out how many of them had those qualities.

It turned out that very few of those projects included the core elements the researchers had identified. The only interactive element in the vast majority of productions was to change the viewpoint, and the user only had anything other than a strict observer role in 8% of the projects. Right now, they concluded, “technologies seem to be developing at a faster rate than journalistic norms and routines connected to their use, leading to immersive productions that do not fulfill the promise of first-person experiences.”

Fake news practices in Indonesian newsrooms during and after the Palu earthquake: A hierarchy-of-influences approach. By Febbie Austina Kwanda and Trisha T.C. Lin in Information, Communication and Society.

When journalists are debunking disinformation (or “fake news”), how do their practices during that debunking process compare with their journalistic routines during ordinary time? Kwanda & Lin asked that question regarding Indonesian journalists, looking in particular at two disinformation stories that arose in the aftermath of the 2018 Palu earthquake and tsunami.

Kwanda and Lin analyzed news content and interviewed journalists to find that while Indonesian journalists say they adhere to Western values like independence and serving as a watchdog, they tended to rely heavily on official government statements about disinformation. This was especially the case for more traditional news outlets. Journalists at independent media sources typically took a more nuanced and multi-sourced approach to disinformation, suggesting that the organization has more influence on disinformation-debunking routines than individual beliefs do.

Asymmetry of partisan media effects?: Examining the reinforcing process of conservative and liberal media with political beliefs. By Jay D. Hmielowski, Myiah J. Hutchens, and Michael A. Beam, in Political Communication.

The reinforcing spirals model proposes the partisan echo chamber effect as a circle: Partisan beliefs lead to more partisan media consumption, which reinforces more partisan beliefs. Hmielowski and his colleagues predicted, as many of us have, that this effect is greater among conservatives than liberals. Using a three-wave survey of the same participants during the 2016 U.S. campaign, they found their prediction was…correct-ish.

On one half of the circle, they found no differences: Conservative and liberal media were equally likely to lead to more polarized political beliefs. But on the other half of the circle, conservative beliefs were significantly more likely to lead to more conservative media consumption than liberal beliefs led to more liberal media consumption. The authors suggest that the difference may be because conservative media may have a sort of “head start” of a couple of decades on liberal media in its prominence and extremism.

Curbing journalistic gender bias: How activating awareness of gender bias in Indian journalists affects their reporting. By Priyanka Kalra and Mark Boukes, in Journalism Practice.

Scholars have long established widespread gender biases in various areas of news coverage, but Kalra and Boukes dug a bit deeper to get at a couple of questions: Are there demographic factors that influence journalists’ gender bias? And does being made aware of their own biases reduce the bias in their work?

Through an experiment with young Indian journalists, they found that there were no significant differences between men and women in levels of gender bias, or in any other major demographic category. But they did find that when journalists were made aware of their gender bias through an implicit-association test, their bias on a subsequent set of editing tasks was significantly reduced. Kalra and Boukes concluded by highlighting the importance of self-awareness exercises in newsroom and j-school bias training.

Soft power, hard news: How journalists at state-funded transnational media legitimize their work. By Kate Wright, Martin Scott, and Mel Bunce, in The International Journal of Press/Politics.

State-funded transnational news organizations such as Al Jazeera, Xinhua, and BBC News World Service are primary sources of international news for much of the Global South, but the relationship of their journalists with the governments that employ them has always been a complex one. Wright and her colleagues looked at how those journalists justified their relationships with those governments and when they might resist their governments’ diplomatic aims.

They interviewed 52 journalists at those organizations (with a particular focus on journalists in Nairobi) and found that journalists like to contrast themselves with the “propaganda” of their governments as well as outlets they see as compromised, such as Russia’s RT. They also emphasize their day-to-day autonomy and argue that their state backing allows them more freedom to cover hard-to-reach or easy-to-ignore news because they’re not constrained by commercial pressures. But they very rarely use that autonomy to exercise any resistance against their governments’ diplomatic efforts.

Embedding, quoting, or paraphrasing? Investigating the effects of political leaders’ tweets in online news articles: The case of Donald Trump. By Delia Dumitrescu and Andrew R.N. Ross, in New Media & Society.

As social media has become an increasingly typical source in news stories, journalists have wrestled with what to do about one person’s tweets more than any other: Donald Trump. Dumitrescu and Ross used an experiment to test the effects on Republican and Democratic readers of embedding, quoting, and paraphrasing incendiary Trump tweets. They were most interested in the effects those tweets had on readers’ perceptions of Trump, and of the article itself.

They found that Trump’s tweets had a favorable effect on Republicans’ attitudes toward him, but only when embedded, and only indirectly, by activating their emotions. (The tweets had no effect on Democrats’ attitudes toward Trump, which were as dismal as you’d expect in all conditions.) Republicans were more distrustful of articles when tweets were quoted, and Democrats were more skeptical when they were quoted or embedded. The results were ambiguous, but the general conclusion was that Republicans liked seeing Trump’s tweets in their original form (perhaps because they could see the likes, retweets, and profile photo), though both parties’ followers seemed to accept paraphrases of tweets as a legitimate journalistic practice.