In the six weeks since George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis and the resulting Black Lives Matters protests that erupted around the country, newsrooms in the United States have been forced to reckon with their own institutional racism that has stifled and derailed news coverage and careers of people of color for decades.

A new study from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism finds that the United States isn’t the only country in which newsroom demographics don’t represent the demographics of the country’s citizens.

NEW factsheet on our website: @rasmus_kleis @MeeraSelva1 & @simgandi look at the number of white and non-white top editors across 100 news organisations in

. Most of them are white.

Read the factsheet herehttps://t.co/ngYK3CUerO

Key findings in this thread pic.twitter.com/vYpksTOhMo

— Reuters Institute (@risj_oxford) July 16, 2020

The Institute studied 100 news outlets from Brazil, South Africa, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States:

In each market, we focused on the top ten offline (TV, print, and radio) and online news brands in terms of weekly usage, as measured in the 2019 Reuters Institute Digital News Report (Newman et al. 2019). (Our focus on the most widely used offline and online brands means that some important outlets are not covered. For example both the Financial Times in the UK and Vox in the US have women of color as editors-in-chief, but they are not included in the sample.)

The authors looked at percentage of top editors and journalists of color, the percentage of people of color in the country (Germany doesn’t collect or publish data about its population’s racial demographics, though the call to change that practice has been renewed in wake of the George Floyd protests, and so the report’s authors aggregated migrant census data to come up with a figure), and the percentage of online news users using at least one source with a non-white top editor.

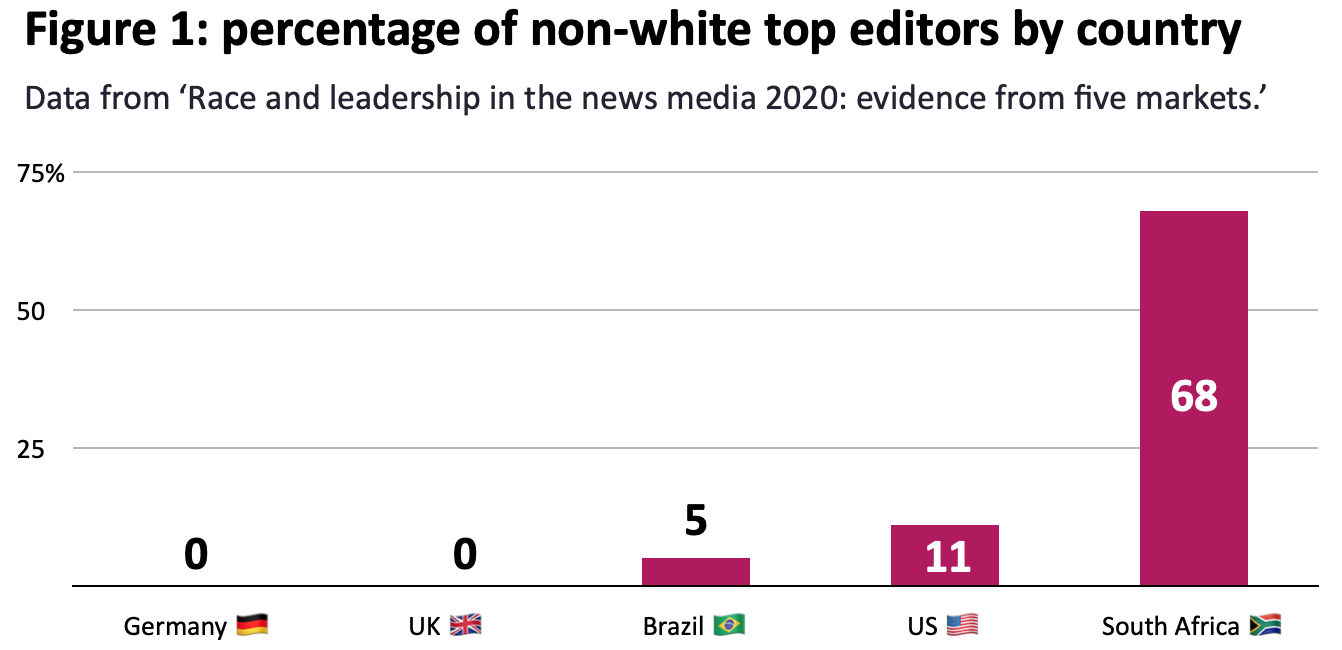

The results aren’t great. The report shows that just 18 percent of the 88 top editors (“We coded observations as missing in cases where both online and offline versions of the same brand share a top editor, so the analysis covers a total of 88 individuals across the 100 brands included”) across the 100 news outlets covered are non-white.

In Germany and the U.K., not a single publication studied had a top editor of color. In the United States, two publications did. (We’ve asked Reuters to confirm who those two U.S. editors are — we assume New York Times’ executive editor Dean Baquet is one, but in light of Lydia Polgreen leaving her HuffPost editor-in-chief position for Gimlet, we weren’t sure who the other person was.)

The problem was most apparent when the Reuters Institute directly compared the country’s non-white population to the country’s percentage of non-white editors.

“It is biggest in percentage points in Brazil, which has a majority non-white population (52%) but only one (5%) non-white top editor in our sample,” the report says. “The gap is very large in both South Africa (91% versus 68%) and the United States (11% versus 40%), in both cases almost 30 percentage points. The gap is numerically smaller in Germany and the UK, but in a way even more glaring given the absence of any non-white top editors in our sample in countries with significant non-white minorities.”

At the risk of stating the obvious, top editors lead the newsroom and determine editorial direction, which stories get the most resources, and how they’re placed in the paper or online. They help decide who gets hired, fired, and promoted. An editor who can’t relate to the way that large portions of the population experience the country has major blindspots, and the power dynamics in the newsroom may make it difficult for other staffers to point them out. “If your newsroom isn’t diverse, you’re failing at journalism,” Swati Sharma, The Atlantic’s managing editor, wrote in a Nieman Lab Prediction in 2017.

Dorothy Byrne, the editor at large of Channel Four, spoke at a Reuters Institute seminar in October 2019 about why diverse newsrooms are better for journalism and for the public. Here’s what she said in context of Brexit coverage:

If your newsroom is dominated by people with a particular mindset and background, you will also literally get the news wrong. That’s what happened with Brexit. Most newsrooms were taken by surprise by the fact that there was a narrow vote in favor of us leaving the EU. Why didn’t journalists see that coming? Well in the UK, far too many of our institutions are in London, and that includes major broadcasters and newspapers. London was pro-Remain so it was easy for journalists living in London to be misled by their interactions with the people around them.

Read the full report here.

In Germany and the UK, both home to millions of people of color, none of the outlets have a non-white top editor. In Brazil, with majority non-white population, one non-white top editor (5%), in the US, two (11%), and in South Africa, a majority (68%) https://t.co/Yhi5wDR761 pic.twitter.com/gWWcBowpug

— Anup Kaphle (@AnupKaphle) July 16, 2020

Relative to their share of the general population, whites are significantly overrepresented among top editors in all five countries, and non-whites significantly underrepresented. https://t.co/AzWSzERCyS

— Katherine Salahi (@KatherineSalahi) July 16, 2020

Disturbing stats show few non-white leaders at the top of major media. https://t.co/sZAkvGYWDB

— juliansher (@juliansher) July 16, 2020