Forgive the staff of BBC News if they seem a bit…shaken these days: They have a lot more than virus fears on their minds.

The world’s largest broadcaster, the BBC has remained iconic through the generations — criticized regularly, of course, but nonetheless capturing the trust and attention of Britons like nothing else. But now it’s facing a remarkable array of new private-sector competitors — and public-sector overseers — that all seem to have Auntie Beeb, in various ways, in their sights. And that puts one of the core purposes of a public service broadcaster — serving as a central, trustworthy anchor in a country’s media ecosystem — at a new level of risk.

(Anyone whose government spends more than $3 per capita on public media per year should feel free to skip this section. You already know this.)

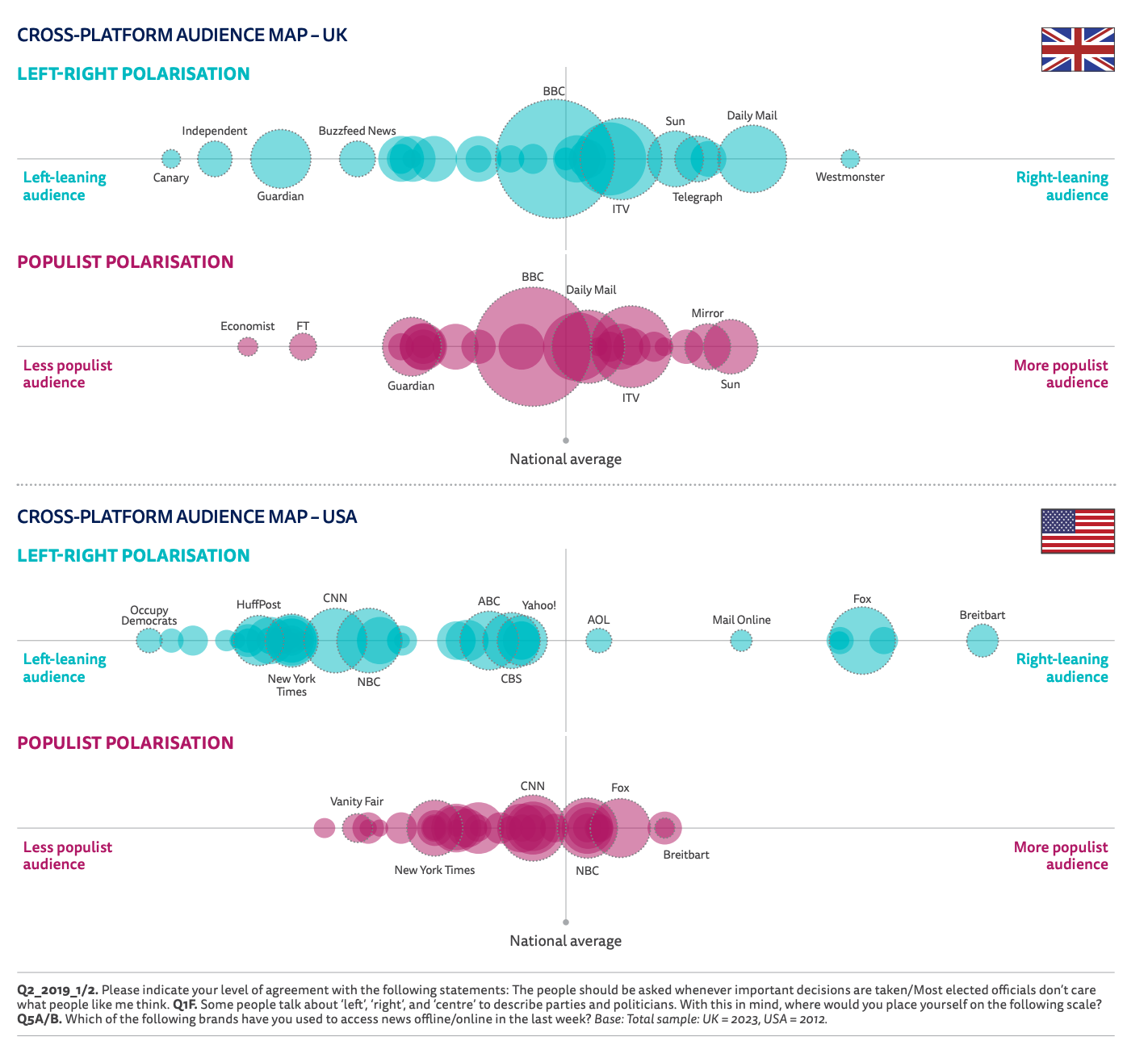

To explain the role the BBC plays in the U.K. to Americans, I like to show them this chart from the 2019 Digital News Report comparing the U.S. and U.K. media universes. Two things to know: The size of each circle here represents the size of a news outlet’s audience. And the left-right axes here represent the average views of each outlet’s audience.

For the two sets of blue circles, we’re talking about the audience’s political views: left = liberal, middle = centrist, right = conservative. And for the two sets of red circles, we’re talking about how populist the audience is: left = not populist, middle = kinda populist, right = super populist.

Now take a look:

Check out those BBC circles in the U.K. survey data, right smack in the middle. The BBC’s audience is almost exactly split between liberals and conservatives. And it’s almost exactly in the middle for populist attitudes as well; the BBC’s audience is much more populist than The Economist’s or the FT’s, but much less populist than readers of the country’s major tabloids. And look how much bigger the BBC’s audience is than any of its peers. The BBC functions as a heat sink for polarization — converting potentially dangerous energy into something the system can more easily deal with.

(Contrast with the United States data for media polarization. There’s no major news organization as squarely in the middle; major broadcast networks (ABC, CBS) and browser-homepages-your-gramps-never-got-around-to-changing (AOL, Yahoo) come closest. The “elite” mainstream media attracts an audience well left of center, and cable news audiences are sharply divided between left and right.)

This is the role that a good, well-resourced public service broadcaster can play in a democracy: a central hub of trust that is enjoyed (or at least tolerated) by a wide swath of the ideological public. When Pew asked people in eight rich Western European democracies what news organizations they trusted most, the country’s public broadcaster finished No. 1 in seven of the eight. (Sorry, Spain.) America’s public broadcasters, PBS and NPR, also score high on trust, but their audiences are smaller and their reputations more split by ideology than those of their European peers.

As Eiri Elvestad and Angela Phillips put it in 2018 in a review of the literature around public service broadcasters (PSBs), all emphases mine:

The Internet has undoubtedly opened up channels of communication for subaltern voices. These voices have not necessarily been progressive and have often been disruptive, but the ability to collectively demonstrate outrage has forced that anger into the mainstream, where it has crossed over from the insulated bubbles of private complaint and into public consciousness.But without the continuing existence of mainstream media, producing common news narratives available to all, at both local and national level, the Internet will too easily become a place that divides us into factions rather than uniting us into communities. The Internet was designed as a space of dispersed networks but democratic debate requires a central space in which ideas can be both heard and contested. Without a centre, there cannot be periphery, merely a number of unconnected and deeply divided spheres.

The research we have analysed tells us that the best way of ensuring that a central space for democratic debate is maintained, and not polluted by accusation and counter-accusation of bias and “fake news,” is by investing in public service media that is rigorously independent and funded for the public good. PSBs will never be capable of satisfying all political factions. That is not their role. They need to be protected for the same reason they were invented: as a bulwark against totalitarianism and a means by which people can speak and be heard across bitter divisions. The compromises necessary for communities to live together cannot be made if we are unable to hear one another.

In every study that examines the effectiveness of news media in ensuring that all citizens are equally well informed, the evidence clearly demonstrates that the provision of publically funded, independent media improves outcomes. Those with access to publicly funded media are better informed, and more aware of debates across the political spectrum or less polarised. There appears also to be some evidence that people are more willing to pay for news media in countries that maintain well-respected and universal public service provision.

(I’m sure none of that “bulwark against totalitarianism” business would resonate with anyone right about now.)

With that background in place, let’s look at the multiple new threats the BBC is facing.

This one launched first, over the summer. The Times (and Sunday Times) have had a relatively positive run the past few years, with its once-mocked hard paywall turning out to be a significant moneymaker. But owner News UK (and Rupert Murdoch) want the sort of influence that’s hard to achieve with subscriber-only content. So they launched Times Radio, a radio/streaming competitor to the BBC’s talk radio flagship, Radio 4. It hired away a bunch of BBC talent and took to the airwaves in June.

Reviews have been mixed, and there’s every possibility that it’ll just end up being a huge cash-burner for Murdoch. But think of it as the opening shot in this round of challenges to the BBC’s airwaves supremacy.

A bigger announcement came over the weekend: One of BBC News’ most familiar faces is leaving to launch a rival TV channel called GB News. (Stateside, meanwhile, WGBH just rebranded as just GBH: It’s a good time to be a GB.)

Andrew Neil has quit the BBC to launch a new right-leaning opinionated rolling news channel which aims to start broadcasting early next year as a rival to the public broadcaster and Sky.

GB News, which has drawn comparisons with Fox News, promises to serve the “vast number of British people who feel underserved and unheard” by existing television news channels, explicitly pitching itself into the middle of the culture war.

Neil said: “We’ve seen a huge gap in the market for a new form of television news…GB News is the most exciting thing to happen in British television news for more than 20 years. We will champion robust, balanced debate and a range of perspectives on the issues that affect everyone in the UK, not just those living in the London area.”

The positioning of GB News — serving the “underserved and unheard” out in Real Britain, not just those London toffs — will be familiar to consumers of American conservative media. Neil is a respected journalist and interviewer — his semi-bewildered conversation with Ben Shapiro last year is a personal favorite — but he also has plenty of conservative bona fides, including as chairman of The Spectator and a previous Thatcher-era run editing The Sunday Times.

There’s nothing wrong with competition, obviously. But it’s noteworthy that GB News’ rhetoric seems to oppose the general idea of a public service broadcaster, and in a very Fox News-inspired mode. (As the right-wing Express put it: “End of BBC?”) Its co-founder, Andrew Cole, has called the BBC “possibly the most biased propaganda machine in the world.” He’s the kind sort who sends emails like: “You really are an offensive little man…Left-wing moron to the core. We do NOT want more illegals in this country and your views are so sickeningly extreme it’s astonishing you get any airtime. I truly despise people like you. Go back to your Left-wing Scottish highlands: or better still go and live in Merkel’s Europe. We do not want you.” Yeah, he’s that guy.

Journalists who have been approached to work for GB News say that despite the UK’s strict broadcasting impartiality rules the channel has been pitched to them as a Right-wing alternative to the BBC. One would-be recruiter corrected their approach to instead describe GB News as an impartial challenger to the “biased BBC.” Cole’s complaints about the news media extend beyond the BBC, however. The Guardian is a “disgusting extremist rag,” he has written, while Bloomberg is “very suspect” and “almost unreadable.” “Journalism has one problem alone — political bias,” he explained on LinkedIn. “[It’s] almost impossible to find one that is balanced and not biased on almost any topic. Modern day journalists are the problem as they claim to be unbiased (some may actually believe this) but in reality they are so, so partisan that it brings the whole profession into disrepute.”

That certainly is one set of opinions. May I suggest the motto “Fair and Balanced”? Or perhaps “We Report, You Decide.” Meanwhile, Sputnik News is excited to see a challenge to the “BBC Propaganda Machine.”

GB News arrives with lots of connections to the Murdoch empire, via past employment and executive hires — but it isn’t a Murdoch project per se. Rupert, Lachlan, and the rest of News Corp have their own Fox-News-a-like on the drawing board for the U.K.

A rival project is being devised in the headquarters of Rupert Murdoch’s British media empire by the former Fox News executive David Rhodes, although it is unclear whether it will result in a traditional TV channel or be online-only…

Rhodes, who was hired by News UK in the spring and most recently served as president of CBS News, is said by sources at the company to have the backing of Lachlan Murdoch, the heir apparent to the business empire. He has been seen taking an interest in the TalkRadio model. A News UK spokesperson declined to comment on the suggestion that a fully fledged news channel was in the works but confirmed he was continuing to work on “video projects.”

As the FT reports, News Corp “has yet to reveal its plans, with the branding and distribution strategy still being hotly debated internally. Both projects see a gap in the UK market for pugnacious, presenter-driven programming that has proved to be lucrative for US cable channels such as MSNBC and Fox News, which earlier this summer became the most-watched US channel in prime time.”

Both GB News and a notional new Murdoch channel would have to navigate the U.K.’s broadcast impartiality rules around maintaining political balance — a stricter version of what the fairness doctrine used to require in the U.S. The path that’s evolved appears to be picking a mix of right and left voices, though with no particular guarantee of equity of power between them. (Imagine Sean Hannity stamping on Alan Colmes’ face — forever.) But while highlighting fights between left and right might meet broadcast standards, it also renders politics ever more polarized.

British prime minister Boris Johnson, though a journalist of sorts for much of his career, is no fan of the BBC. In the runup to his election, he refused to sit for an interview with the broadcaster, alone among major party leaders. (The interviewer? None other than Andrew Neil. Circles within circles.)

“It is not too late. We have an interview prepared. Oven-ready, as Mr Johnson likes to say”

Andrew Neil issues a challenge for Boris Johnson to commit to an interview with him, to face questions on why people have “deemed him to be untrustworthy”https://t.co/daHLxEYn4r pic.twitter.com/oQ21uDdtJe

— BBC Politics (@BBCPolitics) December 5, 2019

Johnson has considered scrapping the license fee that funds the BBC’s operations, replacing it with a voluntary subscription fee and selling off some of its channels. Such a move would obviously do great damage to the institution.

The PM has the power to appoint key figures that oversee the BBC — both at the service itself and at Ofcom, the government regulator of broadcasters (equivalent to America’s FCC). And he appears to be doing so with significant intent, as came out in The Times over the weekend.

Boris Johnson is ushering in a revolution at the top of British broadcasting by offering two of the top jobs in television to outspoken critics of the BBC.

Paul Dacre, the former editor of the Daily Mail, is the prime minister’s choice to become chairman of Ofcom, the broadcasting regulator, replacing Lord Burns, who is due to leave before the end of the year. Lord Moore, the former editor of the Daily Telegraph and biographer of Margaret Thatcher, who has condemned the criminalisation of those who refuse to pay the licence fee, has been asked by the prime minister to take up the post of BBC chairman.

The potential appointments of two right-wing Brexiteers will send shockwaves through the broadcasting establishment. Steve Baker, a Tory MP, said that the appointments of Dacre and Moore could lead to more “conservative and pragmatic” reporting by broadcasters…

As editor of the Mail, Dacre was a fervent critic of BBC bias and waste, backing the publication of the salaries of the corporation’s top talent. He remains on the board of the Mail’s parent company, Associated Newspapers, a position he is likely to come under pressure to relinquish.

(A Johnson minister denied the Times’ report — though only on the thin reed that the two have not been formally offered the jobs yet.)

The Guardian, no friend to Johnson, has helpfully gathered various past comments from Dacre and Moore about the BBC:

“The technology no longer works; nor does the concept. Bureaucracy is the enemy of creativity. The BBC can only be a bureaucracy.” (Moore)

“The BBC has decided to be a secular church and it preaches and tells us what we ought to think about things. So it tells us we shouldn’t support Brexit and we should accept climate change alarmism and we have to all kowtow to the doctrines of diversity. Like the Church of England in the 19th century, I think the church of the BBC has some good aspects, some high standards in some respects and some benefit to the culture. But I do think it should be disestablished.” (Moore)

The BBC “exercises a kind of ‘cultural Marxism’ in which it tries to undermine that conservative society by turning all its values on their heads.” (Dacre)

“Drunk on ‘free’ money from licence-fee payers, the BBC seems institutionally incapable of mending its spendthrift ways or recognising that in this multi-channel, digital age, many of its activities are impossible to justify.” (Dacre)

(Moore has also compared same-sex marriage to marrying your dog, called criticism of Donald Trump’s Muslim ban “more ridiculous than anything he has done,” labels Black Lives Matter a “Marxist movement whose doctrines about white people are explicitly racist,” and believes climate change ain’t no thang, praising Trump for “breaking the spell of climate change mania.”)

It’s the combination of all of these factors — new and well-funded conservative competitors on both radio and TV; skating around fairness standards by pushing news discussion towards ideological conflict and American-cable-news-style yelling panels; a Conservative government that wants to hand control of the BBC to a climate denier and put the former editor of the Daily Frickin’ Mail in charge of enforcing neutrality in news broadcasting — that feels new.

It’s not just new competition; it’s new competition that wouldn’t have been possible under the regulations that have governed British broadcasting for decades. It’s not just a conservative government complaining about public media; it’s turning those complaints into appointments that seem to have little respect for the reason the institution exists in the first place. (See also: the appointment of Steve Bannon pal Michael Pack to oversee Voice of America. And Donald Trump’s annual kabuki elimination of public media funding in his budgets; even if the cuts never actually happen, they serve to polarize public media funding into a partisan issue.)And the real problem is that, once you unleash these forces on the public, there’s no guarantee you can stuff them back in the bottle. The BBC’s existence as that giant heat sink in the middle of British media hasn’t limited the expression of political points of view — it’s enabled it. (Why are British national newspapers so famously diverse in their politics and target markets — from The Guardian on the left to The Telegraph on the right, from the upmarket broadsheets to the populist tabloids? Precisely because the BBC’s centrality and neutrality allows them to be partisan counterpoints. Compare that to the United States, where monopoly local newspapers used to play the role of bland middle-of-the-road outlet in the center of all those charts above.)

Look, I don’t doubt that there are a thousand ways the BBC could improve and needs reform. And I won’t deny that climate deniers and I are unlikely to see eye to eye on much journalistically. But the problem with going after the BBC really isn’t about favoring one political view over another. It’s that a strong trusted public broadcaster plays a huge role in keeping the entire media ecosystem healthy. It provides the central anchor, the shared environment of fact that — as we Americans and lots of other people around the world have found out in recent years — is critical to keeping a democracy from going off the rails. And once it’s gone — or sufficiently kneecapped — it’s awfully hard to bring it back.