Editor’s note: The Front Page is a biweekly newsletter from The Objective, a publication that offers reporting, first-person commentary, and reported essays on how journalism has misrepresented or excluded specific communities in coverage, as well as how newsrooms have treated staff from those communities. We happily share each issue with Nieman Lab readers.

It’s Monday, November 9. This is issue 11 of The Front Page. Before we get into it, a quick plug: If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve been reading over the last few weeks (or months!), we’d love your feedback. If you have time for a 10-15 minute Zoom or phone call, please contact us and we’ll connect with you. In return for your time, when we eventually offer paid membership, we will provide six months free.

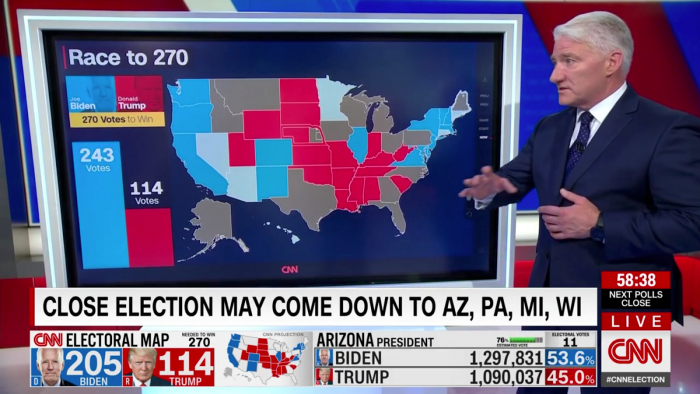

Why are we still doing it like this? As the vote totals rolled in on Election Night, a captive audience around the world on Twitter and in Slack wondered: Does it really have to be this way?

All of the elements of broadcast journalism were played up for effect. During what has been one of the most turbulent years in recent American history (even without an election), why are we still doing this?

my dad is still watching MSNBC and my mom is calling relatives to tell them we know the results definitively and my sister keeps trying to tell me about obscure districts the podcasts said were important and pic.twitter.com/l2YjUa3yPm

— Amal Ahmed (@amalahmed214) November 4, 2020

What could we actually learn on an election night when when many voters sent in their ballots ahead of time and a key swing state had opted not to start counting those ballots early? Why host coverage that suggested the election might end on Election Night if the certified vote totals often take place weeks after the winner is called?

There’s no doubt that, despite the fact that no media executive would say this out loud, there’s a clear answer: chaos and Trump are still good for business.

The anxiety was played up to the max, with an array of panels announcing and repeating projections for each state, and a smorgasbord of former Trump administration officials and Democratic strategists. Of course, there was also the requisite man waiting by the touchscreen of a state and “zooming in” county by county.

The only network where anyone could exhale from the chaos of election night was PBS. It’s no wonder that a channel that does not have to rely solely on advertising money to sustain itself gave anxious viewers a break from the neverending unease of election day. Judy Woodruff was more poised to tackle issues of uncertainty and warned viewers against thinking that anything definitive would be announced that night.

Nobody:

Cable News: "Folks, with 3% reporting, we know this area I'm clicking is a little bit red, but this one is a little bit blue. We still don't know how it's going to play out."

— Gabe Schneider (@gabemschneider) November 4, 2020

On Saturday, the election was called for Joe Biden. But there has got to be a better way: One that treats election night coverage with the seriousness it deserves, rather than treating it like a game.

Who gets a second chance? A racist conservative journalist from the ’90s, apparently. Ruth Shalit Barrett fell out of favor before the people who work on this newsletter were born, but her name might have been mentioned in a lesson on plagiarism. Once a “bubbly prodigy renowned for cultural literacy and political conservatism,” she only recently made a foray back into journalism. However, Barrett didn’t start at the local metro, or freelancing for off-the-wall alt-weeklies for her re-entry. She skipped about 20 years of career-building since the last time she stole someone’s work, and The Atlantic published a 945-word editor’s note and correction and pulled her article about Ivy-League sport schemes off the website after an error was pointed out by Washington Post media critic Eric Wemple. Dozens of errors cropped up once it was confirmed a child had been invented (according to Barrett, to hide her anonymous source’s identity).

Barrett had once gone through the effort of putting pen to paper to announce that The Washington Post had gone too far in its diversity initiatives (this was the mid-90s, but reads like it was published yesterday by Andrew Sullivan). “And the new editorial culture, in its eagerness to avoid offense at all costs, has sought to achieve not simply a racially balanced workplace but racially balanced news coverage, carefully edited to respect the increasingly brittle sensibilities of the relevant groups,” then Barrett continued to argue that The Post was now too soft on Black subjects in news coverage.

The Atlantic dedicated a not-insignificant amount of time in the editor’s note explaining why it thought it was okay to hire her after around 20 years, and apologized for its error. It’s very strange to hire a plagiarist again, but even weirder to just ignore the part where she was bombastically racist.

Really brings home what's wrong with 2020 American journalism when you realize Black journalists *still* have to fight just to be heard but people like Ruth Shalit Barrett are given platform after platform from which to spew their bias. ::coughGreenwaldhack::

— N. K. Jemisin (@nkjemisin) October 31, 2020

Guilds encourage McClatchy and Tribune to #dobetter. Over a year ago, The Washington Post changed its parental leave policy to allow caregivers 20 weeks of paid leave, leading to documentation of policies at other news organizations. According to information gathered at the time by Nieman Lab, Slate offers eight paid weeks for all new parents, The New York Times offers 16 to 18 weeks, and Bloomberg leads the list at 26 paid weeks. However, if you’re one of more than 5,000 employees who works for McClatchy or Tribune, no parental leave is offered.

Recently, One Herald Guild reintroduced that data on Twitter, leading other unions to demand fair family leave, which has been proven to promote diversity in the workplace and positively affect physical and mental health.

While working for @tribpub, I had to return to work before I was ready to with debilitating postpartum anxiety & depression because we couldn’t survive missing my full paycheck. It was the worst experience of my life. Parents working for Tribune deserve better. #DoBetterTribune https://t.co/AsmVckvI0I

— Jordan Sisson (@byjordansisson) October 29, 2020

Staffers at G/O Media are again calling on their company to ensure comprehensive healthcare benefits for transgender and gender-nonconforming employees. Five months ago, the GMG Union presented their plan, which would expand the number of transition-related procedures when compared to the current policy. Management has reportedly not acted on the letter introduced in June.

Leaders at Group Nine Media voluntarily recognized the NowThis Union, a new shop with the Writers Guild of America, East. Eighty-five percent of employees signed union cards, and members have already outlined priorities including transparency, equitable pay, and a thorough examination of and action upon allegations of “racism, discrimination, and sexual misconduct.”

Finally, after bringing the issue to the bargaining table in May, Time Union announced that management has tentatively agreed to ban nondisclosure agreements in sexual misconduct cases. If your organization lacks clear sexual harassment and misconduct policies or resources, this toolkit from the Society of Professional Journalists may be helpful.

Q&A: Diversity Hire with Arjun Ram Srivatsa and Kevin Lozano. A lot has been said about “POC” and “diversity” in media, but Arjun Ram Srivatsa and Kevin Lozano’s podcast questions the specificity of that language. On Diversity Hire, Srivatsa and Lozano challenge the idea that POC is an adequate descriptor, instead opting to discuss specific experiences of race and class. The podcast has hosted guests like The New York Times’ Jazmine Hughes, Time To Say Goodbye cohost Jay Caspian Kang, and Gaby Del Valle, a freelance immigration reporter, to talk about their careers and the nebulous notion of “POC in Media”.

The Objective sat down with them to talk about the podcast, class, unpaid work on diversity committees, and everyone’s secret dream of opening a wine bar.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity. You can read the rest here.

Siri Chilukuri: What does “POC in media” mean or not mean?

Kevin Lozano: POC is the wrong word for the kind of problem that we’re facing. Diversity is the wrong word too, and D&I too. These are kind of corporate catchalls that make it harder to point to the specificity of the problem of representation in the media which is the problems of each marginal group are very specific and we should be as specific as possible in order to address those problems. For example, the problems faced by East Asians in Flushing are very different than the problems faced by Indian-Americans in the Bay Area. I think such large encompassing terms flatten the experiences of like groups of people that can often contradict long held beliefs or stereotypes. So the reason we don’t like POC is that I think it prevents us from having a more nuanced conversation about identity.

Ram Srivatsa: Class.

Lozano: And class, especially class. I think POC really flattens class experience, even amongst people who are nominally part of the same racial group. There are really upwardly mobile Asian Americans who immigrated to this country to get graduate degrees and then there are recent immigrants who work at a restaurant. What do those people share? They have the same racial category but their class experience is so divergent. When the children of those people are applying for jobs they’re seen as the same but their class experiences is completely different.

Ram Srivatsa: Beyond that, the Harvard grad who applies to a job at The New York Times is going to be asked to report on the restaurant worker who just moved here and they have absolutely no idea what those people are going through. One thing about our podcast — and this is not on purpose, this is just people we’ve selected — I think only two of our 15 guests went to public college. The majority of them went to elite East Coast universities and, I mean, that just goes to show we’re having leftist writers who have good politics — like, similar politics to us but the track record is always going to be the same.

ICYMI at The Objective. In “Paid journalism internships are often the best chance to build a career. Are they enough?” Izz Scott LaMagdeleine, writes about how the vague notion of a paid internship doesn’t solve class inequities in journalism.

What’s happening. $$$ denotes a paid event.

A bit more media.

This edition of The Front Page was written by Holly Piepenburg and Marlee Baldridge, and Siri Chilukuri, with a Q&A by Chilukuri and editing by Gabe Schneider. The Objective was cofounded by Schneider, the Washington correspondent for MinnPost, and Baldridge, a Master’s student at the University of Missouri (and a former Google News Initiative fellow at Nieman Lab).