What do people see in their Facebook feeds? How much news do they encounter there — from legitimate outlets or from those known for sowing misinformation? Are most people’s accounts cesspools of fake news and garbage from disreputable sites, or do they see stories from Facebook’s trusted news partners?

Or…do they mostly see innocuous memes, baby pictures, and cute animal stories?

Debate over these questions has raged for years, especially in the weeks leading up to the highly fraught 2020 U.S. presidential election. Answers depend on who you ask and what tools you use.

Look at daily engagement data from the Facebook-owned CrowdTangle, which measures the reactions, shares, and comments a post gets, and you’ll see lists dominated by Donald Trump and far-right pundits.

Facebook claims its internal data paints a different picture. The company says that the posts with the highest engagement aren’t actually the ones that reach the most people, and that the average Facebook user sees little political content. But since Facebook doesn’t make its reach data public, researchers who want to get a sense of what the average Facebook user sees are generally forced to rely on anecdotes, company statements, or CrowdTangle.

I decided to approach the question in a different way — by peeking directly into people’s Facebook feeds. Between October 1 and 31, 2020, I surveyed the Facebook habits of, and got real News Feed samples from, 306 people aged 18 or older in the United States. I reached them using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform, asking them to send me screenshots of the first 10 posts in their Facebook feeds. (I used the images for classification purposes only. No identifying information is referenced in this story.) After cleaning the data and removing entries that were submitted incorrectly, I had data from 173 people — a total sample of 1,730 Facebook posts. (See more in the methodology section at the bottom of this post. You can see my spreadsheet here.)

In doing this project, I built on Nieman Lab research from three years ago, conducted by my then-colleague Shan Wang, who is now a senior editor at The Atlantic. (We miss you, Shan!) At the time, Shan found that people saw surprisingly little news in their Facebook feeds. Three years later, in one of the craziest news months in U.S. history, my findings were similar: People saw surprisingly little news in their Facebook feeds. (I counted news both from publishers and from links shared by friends and family.)October — which kicked off with Donald Trump revealing that he and the First Lady had contracted coronavirus — was a nonstop news month in the most relentless news year in decades. If there were ever a month that you’d expect people to see a lot of news at the top of their Facebook feeds, it would be October 2020.

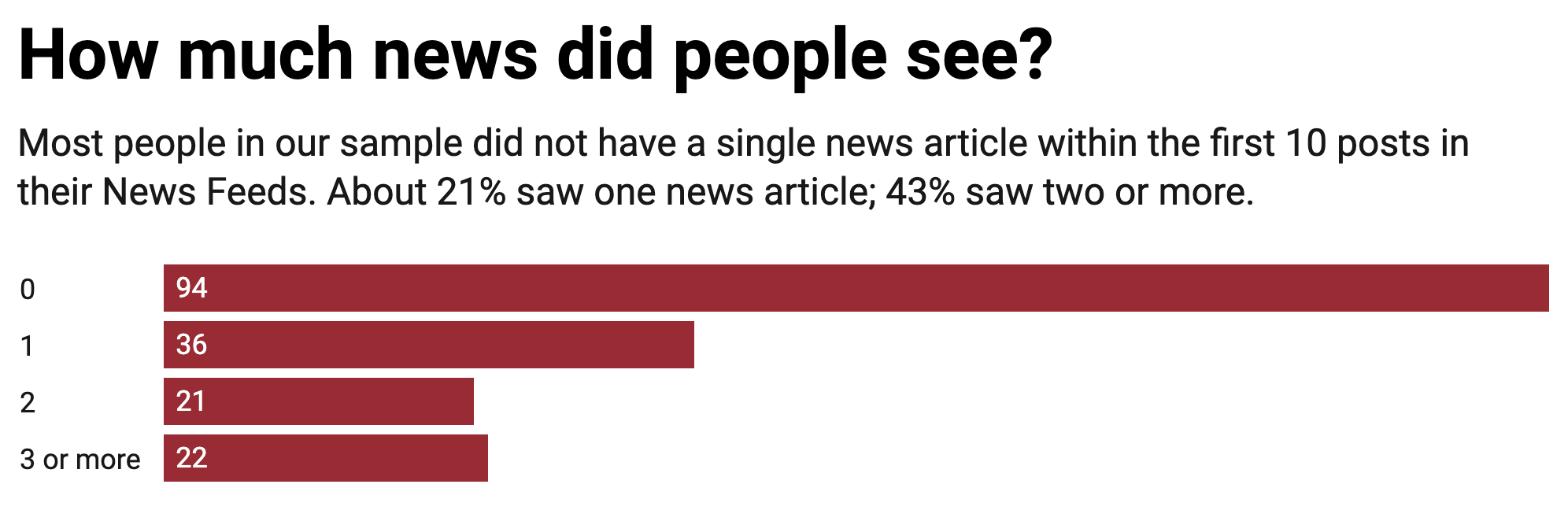

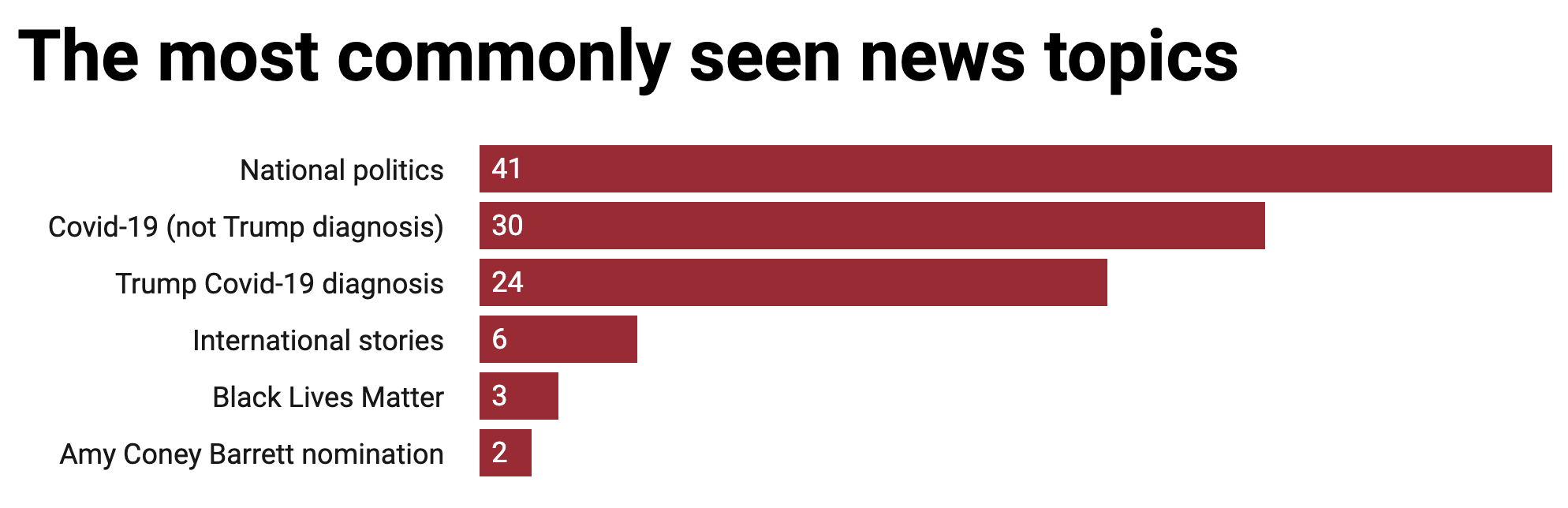

Nope. Even using a very generous definition of news (“Guy rollerblades with 75-pound dog on his back“), the majority of people in our survey (54%) saw no news within the first 10 posts in their feeds at all. In Shan’s 2017 survey, that figure was 50%.

79 people — or 46% of the sample — saw at least one news article.

Hard news — which I defined as serious and important stories about national politics, Covid-19, and so on — was the most common type in my sample. In total, out of the 1,730 posts I looked at, 178 were news stories; of those, I classified 138 as hard news. Of the people who encountered any news at all, 81% came across at least one hard news story. The other 19% saw only soft news (weather, elephants smashing pumpkins, “Irish court rules subway bread is not bread“).

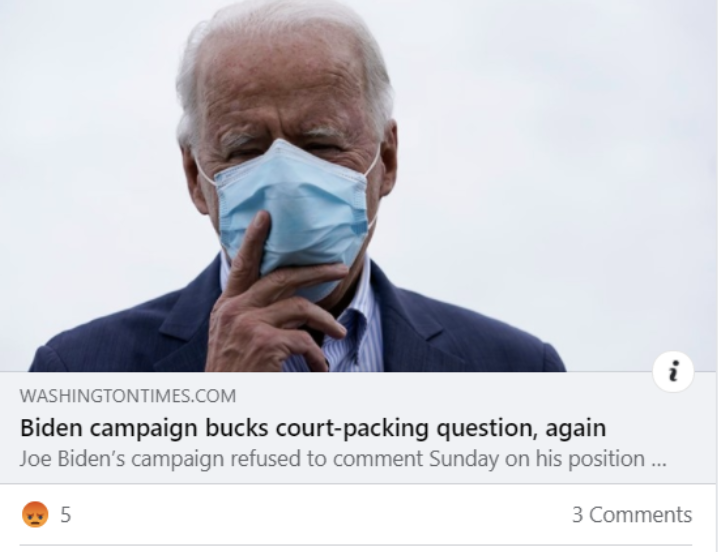

There were lots of stories about national politics or Covid-19 (or, sometimes, the intersection between the two). Trump’s Covid-19 diagnosis and its aftermath was a huge story that I coded separately from other news stories about Covid-19: 17% of the hard news articles in my sample were about Trump contracting Covid. (I put stories about other politicians contracting Covid-19 in the “general” Covid-19 category.)

I didn’t find any completely fake news (of the “Pope endorses Donald Trump” variety) in this survey. Exactly zero of the 1,730 posts I looked at had been flagged by Facebook for including false or disputed information. Most of the hard news articles in the sample were published by mainstream national news outlets.

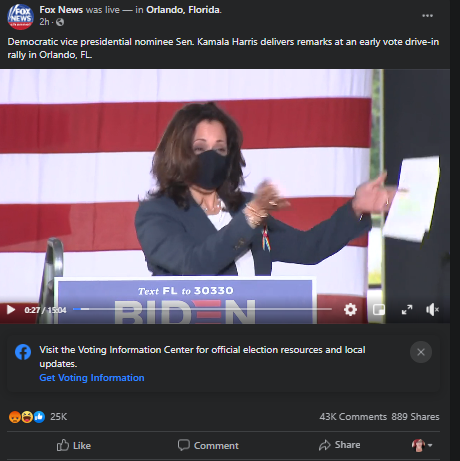

Still, partisan sites like Fox News, the pro-Trump One America News Network, and The Western Journal made it into the list of top 10 publications, although the individual Fox News articles were straight news, like these ones:

Facebook reportedly limited The Western Journal’s reach last year after it published deceptive stories, but it still did well in our sample. Of the four Western Journal stories that our respondents saw in their feeds, two — one about Trump’s diversity order and one about the plane crash — were written as straight news. The plane crash story was syndicated from the AP.

I saw one hard news article from each of the following outlets:

AARP, ABC, Al Jazeera, AP, Auburn Plainsman, Boulder Weekly, Business Insider, BuzzFeed News, Catoosa-Walker News, CNBC, Commercial Appeal, Corvallis Gazette-Times, Counterpunch, The Daily Caller, Daily Mail, The Federalist, FiveThirtyEight Forbes, Fox 2 Now, Fox 5 Vegas, Fox 6 Milwaukee, The Guardian, Holy City Sinner, Honolulu Star-Advertiser, HuffPost, LifeSiteNews.com, Majority Report, NBC CT, Neon Nettle, New Bedford Guide, The New York Post, The New Yorker, News and Guts, News2Share, News4JAX WJXT4, Newsbreak, Newsy, OUDaily, Police Tribune, Real STL News, Reuters, The Blaze, The Bulletin, The North Star, The Week, Time, Times of Israel, TMZ, Trending World by The Epoch Times, Truthout, USA Today, WAFF, Wall Street Journal, The Washington Examiner, The Washington Post, The Washington Times, Wavy TV 10, Westword, WMUR, WRIC ABC-8, WSWS (World Socialist Web Site), Yahoo

Out of those, The Blaze, Counterpunch, The Daily Caller, The Federalist, LifeSiteNews.com, Majority Report, Neon Nettle, Police Tribune, Trending World by The Epoch Times, Truthout, The Washington Examiner, The Washington Times, and WSWS can be considered partisan news outlets, but for the most part their stories in my sample weren’t particularly inflammatory. Here are a couple examples:

As I mentioned before, very little soft news appeared in people’s feeds. I saw two soft news articles each from CBS, The Dodo, ScreenRant, and Us Weekly. No other news outlet appeared in the sample more than once.

Politicians and pundits often appear in lists of the top posts in Facebook. Here, for instance, is a list of Facebook’s top-engaged link posts for October:

Some month-end data from Facebook: in October, the most-engaged link posts from U.S. pages (excluding some UNICEF posts that were boosted by FB) came from:

1. Franklin Graham

2. Donald J. Trump

3. Graham

4. Trump

5. Trump

6. Graham

7. Graham

8. Graham

9. Fox News

10. Graham— Kevin Roose (@kevinroose) November 1, 2020

In the pundit division, total interactions on all posts (including photos/videos) for October:

Occupy Democrats: 61 million

Dan Bongino: 48 million

The Other 98%: 26 million

Ben Shapiro: 24 million

David J. Harris Jr.: 12 million

Robert Reich: 11 million

Sean Hannity: 9 million— Kevin Roose (@kevinroose) November 1, 2020

In my sample of 1,730 posts, there were 40 political posts (2%). I saw one post from the conservative pundit Dan Bongino (but it was in the feed of a respondent who identified as “very liberal” and also had a New York Times article in their feed) and one from Donald Trump.

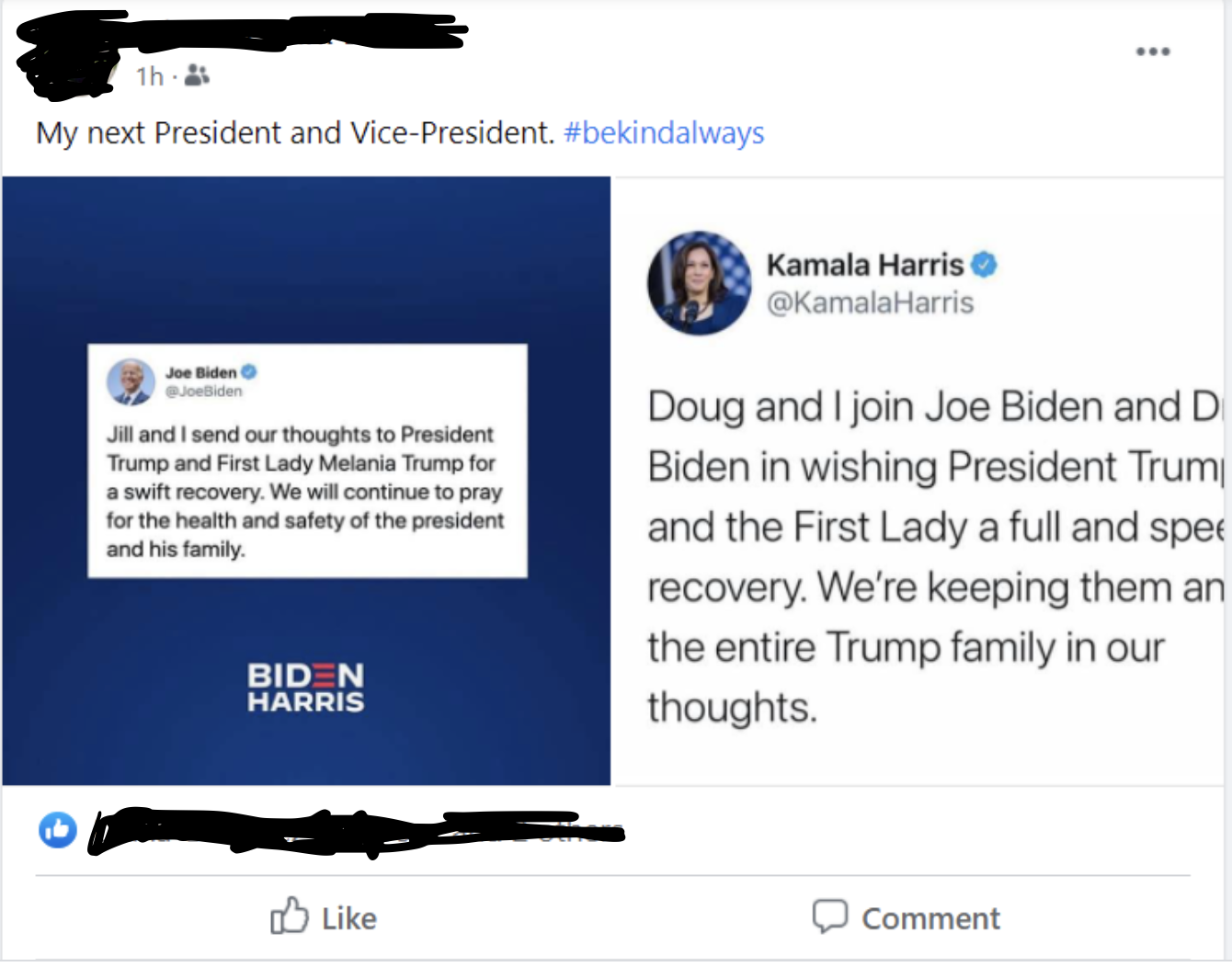

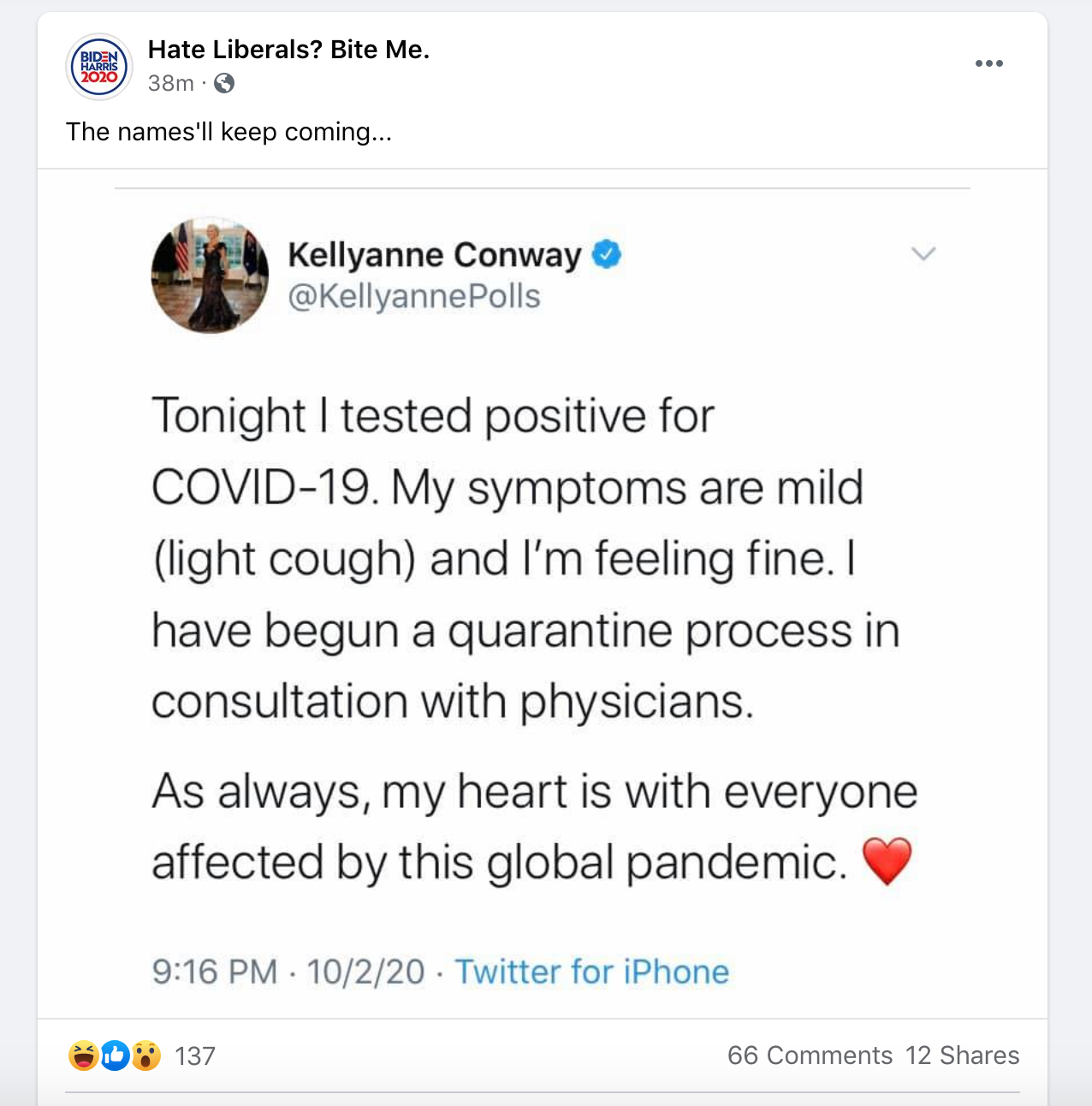

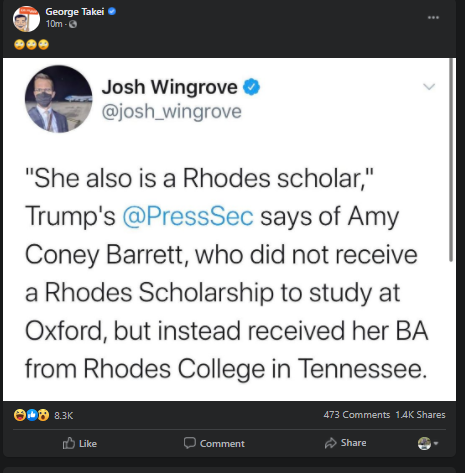

While my sample was small, the type of political content I saw most frequently was the “tweet screenshot” — a post that simply consisted of a screenshot of a tweet by a political figure or a tweet about politics, sometimes along a line or two of commentary. Tweet screenshots accounted for 30% of the political posts I saw. While Twitter is still used by far fewer people than Facebook, it’s interesting to see how tweets make their way onto Facebook and Instagram. (It also raises questions about whether and how Facebook will be able to fact-check these tweet screenshots, which are just image files.)

While my sample was small, the type of political content I saw most frequently was the “tweet screenshot” — a post that simply consisted of a screenshot of a tweet by a political figure or a tweet about politics, sometimes along a line or two of commentary. Tweet screenshots accounted for 30% of the political posts I saw. While Twitter is still used by far fewer people than Facebook, it’s interesting to see how tweets make their way onto Facebook and Instagram. (It also raises questions about whether and how Facebook will be able to fact-check these tweet screenshots, which are just image files.)

In recent months Kevin Roose, a technology reporter for The New York Times, has consistently used CrowdTangle and NewsWhip data to assert that Facebook is teeming with misinformation, based on high engagement figures (likes, shares, etc.) for news stories from partisan outlets. He runs a Twitter account, Facebook’s Top 10, that each day provides a list of the 10 top-performing link posts by U.S. Facebook pages. The top-10 list is almost invariably filled with posts from far-right sites and politicians, including conspiracy-driven sites like Gateway Pundit and Infowars. Here, for instance, is the Top 10 post for November 19:

The top-performing link posts by U.S. Facebook pages in the last 24 hours are from:

1. Dan Bongino

2. Donald J. Trump

3. Dan Bongino

4. Fox News

5. Franklin Graham

6. Fox News

7. Classic Hollywood | Los Angeles Times

8. Breitbart

9. Bernie Sanders

10. CNN— Facebook's Top 10 (@FacebooksTop10) November 19, 2020

It’s a credit to Roose’s hard work that Facebook has been forced to respond. Over the past few months, company representatives have asserted that the high-engagement posts that appear on Roose’s lists aren’t actually what most people see in their feeds. Facebook isn’t asserting that the CrowdTangle data is wrong, exactly — but here’s John Hegeman, the VP of News Feed, in July:

3/6 CrowdTangle calculates interactions, not impressions, which is # of ppl who see posts. Pages in these lists see high engagement because followers, or those interacting w/ the posts, are passionate. But it shouldn't be confused with what's most popular.

— John Hegeman (@johnwhegeman) July 20, 2020

It’s a little rich for Facebook to downplay the importance of post engagement — how much interaction its users have with a given piece of content — given that Facebook is, at its core, an enormous engine for the creation of engagement. When Mark Zuckerberg explained why he was reducing the amount of news in News Feed in 2018, he said too often “reading news…is just a passive experience” and that his goal was to increase how much news and other Facebook content “encourage[s] meaningful interactions between people.”

But: Rather than looking only at engagement, the company argues, calculations of the most popular content on Facebook should be made based on posts’ reach — how many people actually see the content. Alex Schultz, Facebook’s VP of analytics and chief marketing officer, wrote on November 10:

The vast majority of what people in the US see on Facebook is in their News Feed. Most of the content people see there, even in an election season, is not about politics. In fact, based on our analysis, political content makes up about 6% of what you see on Facebook. This includes posts from friends or from Pages (which are public profiles created by businesses, brands, celebrities, media outlets, causes and the like). […]

Engagement does not predict reach. (You can find additional explanation in these articles about personalization in News Feed, public comments and reducing the spread of problematic content.)

The following list, Facebook says, is “more indicative of what people actually see on Facebook, and the publishers listed are more indicative of which outlets people see on Facebook dealing with politics”:

And again, here’s the list of most-seen news outlets in my sample:

My survey is way too small to settle the debate. But the list of most-seen publishers in my sample falls somewhere between Facebook’s “reach” list and one of Roose’s “engagement” lists. It’s topped by mainstream publishers, sure, but it includes partisan outlets too.

141 of the 1,730 posts in my sample could be described as political content (101 news articles + the 40 political posts I described above). In other words, in this survey, political content made up about 8% of what people saw. That’s pretty close to Facebook’s claimed 6%.

My sample size was small and shouldn’t be used to draw sweeping conclusions about Facebook news consumers overall. With that in mind, here’s what I found. The hints here may provide opportunities for further study.

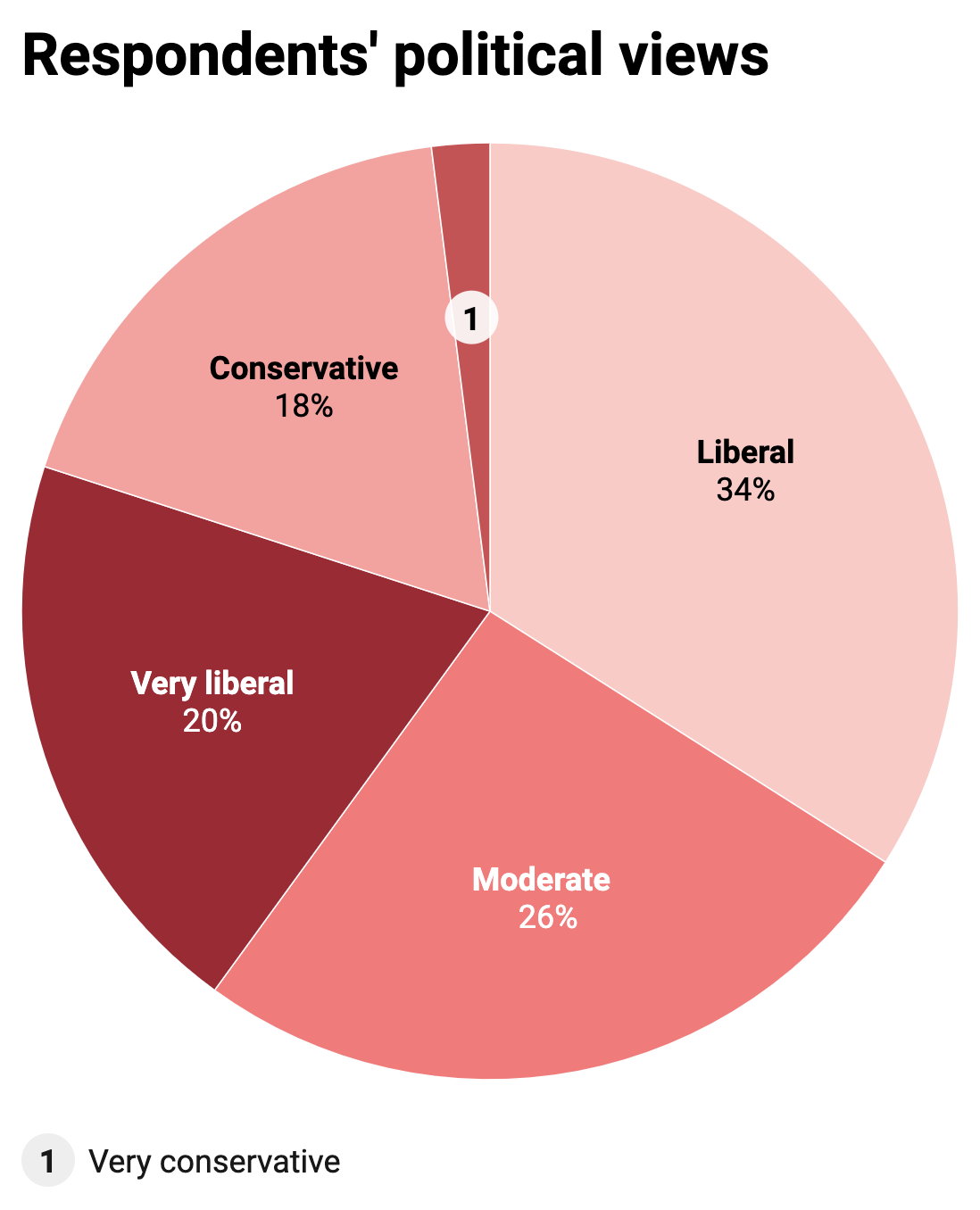

Respondents were young (81% of them were under the age of 45). More than three-quarters said they checked Facebook either “a few” (44%) or “many” (34%) times per day. Sixty-five percent said they “ever” check Facebook for news, and most respondents said they consume news outside of Facebook — either “often” (49%) or “sometimes” (40%). Most of them (60%) primarily check Facebook from their phones. The chart on the right shows how they identified politically — like many Mechanical Turkers, they skewed liberal.

Respondents were young (81% of them were under the age of 45). More than three-quarters said they checked Facebook either “a few” (44%) or “many” (34%) times per day. Sixty-five percent said they “ever” check Facebook for news, and most respondents said they consume news outside of Facebook — either “often” (49%) or “sometimes” (40%). Most of them (60%) primarily check Facebook from their phones. The chart on the right shows how they identified politically — like many Mechanical Turkers, they skewed liberal.

A little over a third of respondents (35%) said that they don’t ever check Facebook for news. Those people saw an average of 0.4 news articles within the first 10 posts of their feed. The 65% of respondents who said they do check Facebook for news saw an average of 0.58 articles. Still, a little more than half of that group (51%) saw no news articles within the first 10 posts of their feed.

— People who identified as conservative or very conservative saw the most news in their feeds — an average of 0.64 news articles.

— People who said they consume news outside of Facebook (from newspapers, TV, news sites, whatever) also see more news on Facebook. Those who “sometimes” or “often” consume news outside of Facebook saw an average of 0.55 articles in their feeds. Those who “hardly ever” or “never” consume news outside of Facebook saw an average of 0.19 articles.

— People with fewer Facebook friends see more news: People with 0 to 400 friends saw an average of 0.58 articles, while people with 401 to 1,000 friends saw an average of 0.39 articles.

Methodology

I reached users through CloudResearch (formerly TurkPrime), a platform that hooks into Amazon’s MTurk and returns batches of responses. I asked respondents nine multiple choice questions through a Qualtrics survey. Choices were offered as ranges. I also asked them to link to private Imgur uploads of screenshots of the first 10 posts each respondent saw in their Facebook feed.

I paid respondents $0.75 each for the survey and the screenshots. I received many more completed surveys at the beginning of the month than toward the end of the month, perhaps because I limited the survey to CloudResearch approved participants, who have been vetted by the company (“participants on this list have shown prior evidence of attention and engagement and represent various levels of experience on MTurk, different ages, races, incomes, and are generally demographically similar to other MTurk workers.”) I received 306 responses, but 133 were unusable (many respondents didn’t properly upload screenshots — also a problem in our 2017 previous survey — and I hope to find a way to address this in future surveys. One way to address it might be to pay more).

The survey asked for age; country where they were checking Facebook from (there was an IP-address restriction already, but we included this extra step); number of friends on Facebook; frequency with which respondents checked Facebook each day; whether respondents checked Facebook specifically to get news (news was defined as “information about events and issues that involve more than just friends or family”); the number of news organizations a respondent had “liked” on Facebook; the device they used to access Facebook; how often a respondent either read, watched, or listened to the news outside of Facebook; and self-described political views (very liberal, liberal, moderate, conservative or very conservative). Choices were offered as ranges.

In our 2017 survey, it was hard to decide whether or not certain posts should count as news. This time around, it was easier because I differentiated between hard news and soft news.