What happens when a tech company turns off the traffic tap? We’ve had occasion to find out over the years.

There was the time in 2014 when Google removed Spanish publishers from Google News; web users’ news consumption dropped 20 percent.

Or the time Facebook decided to remove news stories from its News Feed in six countries; one Guatemalan news site lost two-thirds of its traffic overnight.

Or that autumn day in 2018 when Facebook went down altogether for about 45 minutes. Direct and search traffic to news publishers spiked as users went looking for something else to scroll through — enough that total traffic to news sites actually went up in that brief Facebookless respite.

Our latest datapoint comes from the Antipodeans down under, where a battle between Australian regulators and the two tech giants has come to a head. Australia wants to force Facebook to pay Australian publishers for some abstract notion of the “value” their stories produce for Facebook. (It’s a bit as if TV network had to pay Procter & Gamble for the value of all those 30-second Crest-themed short films that run between the longer bits.)

Faced with that impending requirement, Facebook told regulators to go [vulgar Australian slang tk tk] themselves and went nuclear: “In response to Australia’s proposed new Media Bargaining law, Facebook will restrict publishers and people in Australia from sharing or viewing Australian and international news content.”

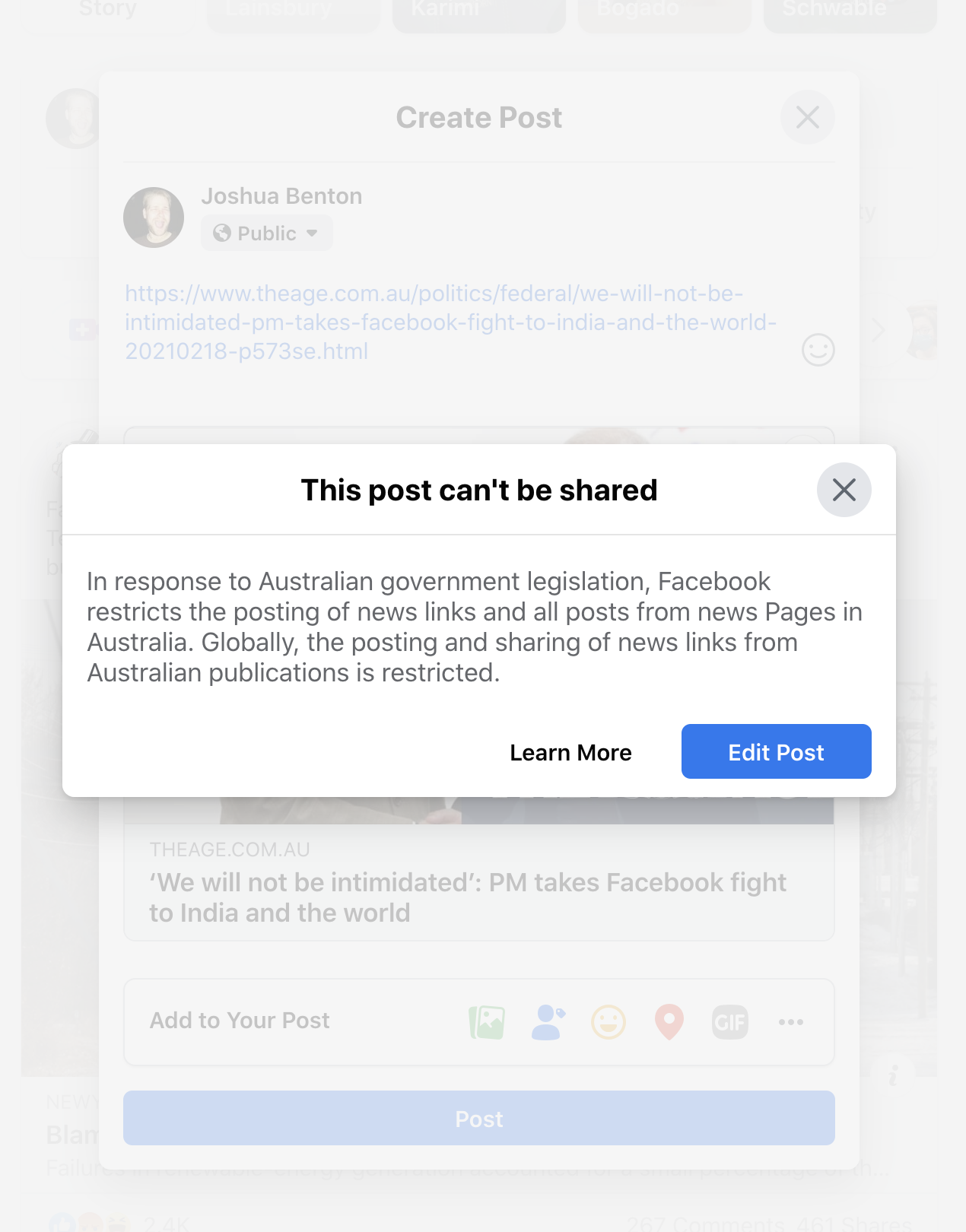

Even people outside Australia can no longer share stories from Australian publishers big and small, from the Sydney Morning Herald all the way to the Goondiwindi Argus. Try to post a link to a story from The Age and this is what you get:

This is what an Australian newspaper’s Facebook page looks like right now: all liked up but nowhere to go.

So what has this done to traffic for Australian publishers? Our friends at Chartbeat shared some preliminary data with us, and the numbers ain’t good.

Let’s first look specifically at Facebook referrals — traffic that comes from Facebook’s properties to an Australian news publisher’s website. This is what happened to Facebook referral traffic from within Australia to those publishers.

The X-axis here is a span of 38 hours, starting at 11 a.m. on Wednesday, Sydney time. The first half of the chart looks pretty normal — a nice hearty plateau of Facebook traffic in the afternoon and evening Wednesday, followed by a normal overnight dip as Australians go to sleep. The next morning, traffic started to creep up as it would on a typical day — until Facebook turns off the tap around 5:30 a.m. local time.

From that point, daytime traffic looks like the dead of night. In the 6 p.m. hour on Wednesday, Facebook sent 201,000 pageviews to Australian publishers. Twenty-four hours later, it sent just 14,000 — a 93 percent drop.

(Why not zero? There are still a few places where you can find a publisher link on Facebook, like the link to its homepage on its Facebook Page, along with older links posted before the shutoff. And it seems at least some people are still able to post links — I found several Australian politicians who seemed able to link. And a site like The Guardian Australia is in a sort of grey area, seemingly able to link to Australian stories because they’re hosted on the international theguardian.com domain.)

What about the vast Australian diaspora, all the Bruces and Sheilas who left to make their fortunes but still want to know if Geelong could top St. Kilda? Here’s what their Facebook referral traffic looked like. (The times here are in GMT, not Sydney time, and note that the scale on the Y-axis is smaller than in the last chart.)

The peak here is roughly daytime in Europe — but again, traffic takes its usual overnight dip and then never comes back. The last 24 hours here move from 43,000 hourly pageviews to 3,000.

The decline in Facebook traffic from overseas has a particularly big impact because a larger share of publishers’ international traffic flows through Facebook than does its domestic audience. Call it the Law of Traffic Proximity: People who live near a local news outlet are more likely to head directly to the local daily’s website, while people who live farther away are more likely to click on a News Feed link that reminds them of home.

This is just traffic from Facebook — how big a deal is it in terms of traffic overall? Here’s how Chartbeat summed it up:

Unfortunately, Facebook’s disappearance has resulted in a hit to publishers’ traffic numbers: when Facebook traffic dropped off, overall Australian traffic did not shift to other platforms.

This drop has been seen most dramatically in traffic to Australian sites from readers outside of Australia: Because that readership was so driven by Facebook, overall this outside-Australia traffic has fallen day-over-day by over 20% (and looks like it’s fallen a bit more in recent hours).

We also see a large drop in traffic from readers within Australia: At 1 p.m. Eastern time on Wednesday [just before Facebook made the change], over 15% of visits from within Australia were being driven by Facebook. Traffic steadily fell from there, and by 8 p.m., less than 5% of visits were being driven by Facebook.

If this shutoff continues, I’d imagine that the more dedicated news consumers might adapt in ways that are, on net, positive for publishers. Maybe they go to a newspaper’s website more often, or they sign up for a daily newsletter to get their fix. But the casual reader of news on Facebook — and that’s most users, given that news stories make up only about 4 percent of the typical News Feed — might just skip out on news entirely.

Maybe Facebook and Australia will mend their rabbit-proof fences and this state of affairs will be short-lived. But until then, publishers have probably lost a decent-sized chunk of their audience.