If you’ve ever had to cite or find information from a city council meeting, you know how frustrating it can be to find what you’re looking for. Lots of times meeting minutes aren’t uploaded until after they’re approved, which means waiting anywhere between a week and a month, depending on how frequently council meets. Watching video recordings or listening to your own audio recording to find what you’re looking for is time consuming.

If you have to find things from multiple meetings, repeat the same tedious steps.

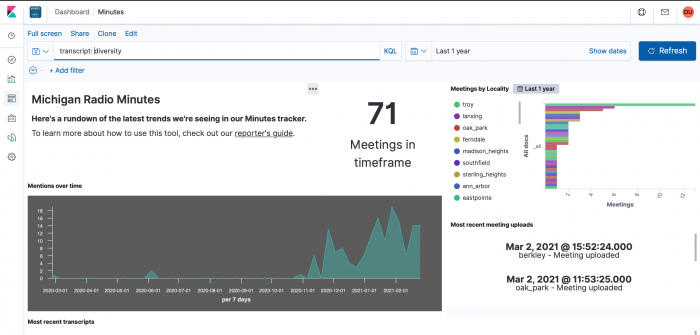

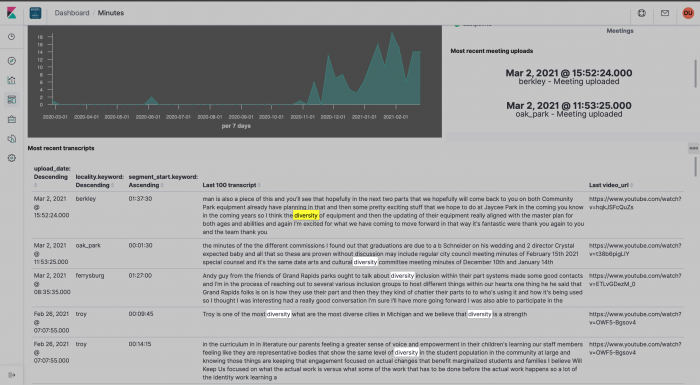

But recently, journalists from Michigan Radio, the NPR station in the state, have been using a database they built in-house to better sift through public meetings. The database is called Minutes and it searches, downloads, and transcribes videos of public meetings in a few dozen cities in Michigan. The project is funded by the Google News Initiative’s Innovation Challenge.

Meeting are already public in Michigan because of the Open Meetings Act, but there was no searchable index of meetings from across the state, Dustin Dwyer, a Michigan radio bureau reporter and 2018 Nieman Fellow, said.

Just because information is public doesn’t mean it’s easy to find. Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy gets it. And so does @MichiganRadio. We’ve got an exciting new project launching tomorrow that will help you get at what’s in that locked cabinet. Stay tuned! pic.twitter.com/oGBZDwizNc

— dustindwyer (@dustindwyer) March 2, 2021

“It is unbelievably complicated to find out what happens in these meetings, even though all the information is online,” Dwyer said. “We’re trying to make the content of the meetings searchable, so that you don’t have to spend a lot of time scrolling through the agenda finding out when they’re talking about the thing that is important to you. [Instead], you can search for the information and get a meaningful result. It’s overcoming an informational barrier around these meetings.”

The tool is called Minutes. An application code monitors YouTube channels it can pull from, Michigan Radio’s digital tech specialist Brad Gowland explained. When it sees that there’s new videos, it gets the audio of the video, and it transcribes it in 45-second chunks so there’s enough text to transcribe complete sentences. So if a reporter is looking for a certain topic, they can search through the transcripts to find legible sentences about what they’re looking for, and then they can go to YouTube to watch the full video and pull out soundbites.

The database allows reporters to keep tabs on issues across the the state, even in places where there aren’t any Michigan Radio reporters covering them regularly. It’s somewhat inspired by tools like City Scrapers and Documenters, both of which are open-source, collaborative community efforts to make information from and about public meetings in select cities more readily accessible. Minutes doesn’t create an excuse for a newsroom to not cover a city council meeting, Dwyer said, but it helps catch things that might otherwise slip through the cracks. Often, issues become more important for coverage when it’s clear that they exist in multiple places. Minutes helps figure that out.

“I live in Grand Rapids so if something is happening in Grand Rapids, I’m going say it’s kind of important, but I may not know that it’s also happening in other communities on the opposite side of the state that we don’t normally cover,” Dwyer said. “But then there’s people showing up at those meetings every week giving public comments and saying ‘this is important to me.’ If we don’t know that those things are happening in other parts of the state, we may not realize how big or how important something is or how widespread it is. Being able to draw those connections is a big part of what this database is about for our reporters.”

The Minutes database and its transcripts aren’t available to use to the public because they aren’t checked for errors (the program could hear the word “vaccine” and transcribe “Maxine”). It also isn’t a definitive database of every meeting in Michigan because it still takes time to process so many videos and costs money to store those large files. But since the program is already downloading audio from the meetings, it then sends the audio to one of Michigan Radio’s 42 new podcast feeds. That means that anyone can listen to a public meeting in 42 of Michigan’s cities as a podcast. Michigan is a large state with fewer and fewer reporters, Dwyer and Gowland wanted to be able to provide public meetings information to people who are interested in them, but it’s difficult to continue the current model: reporters attending meetings and producing stories about them.

“I see this already available in so many other aspects of local life,” Dwyer said. “If I want to know what the weather is in my city or what the weather was yesterday, I can know that immediately. If I want to know high school prep scores, I can know that immediately. All of these things are already indexed and searchable and if I type it into Google or ask a device I get an immediate, useful result. Why in the heck can’t it be that easy to find out what’s happening within my local government?”