The act of throwing money around to resolve an issue? COIN TOSS. One with four legs and many hands? CARD TABLE. Drop just a drop? MICRODOSE. What these have in common? CROSSWORD CLUES.

Clues, to be specific, in The New Yorker’s thrice-weekly crossword puzzle. The magazine launched its first-ever Puzzles & Games Dept. at the end of 2019 and has rolled out a number of digital goodies for solvers since, including the social distancing-compliant Partner Mode, a newsletter, special holiday puzzles, a way to play on the New Yorker Today app, and behind-the-scenes videos. (Here’s one entitled “Crossword Puzzles with a Side of Millennial Socialism” and another with tips on how to solve those tricky British-style cryptic crosswords.) The team is growing, and now includes fact-checkers and a dedicated copy editor. And, just last month, The New Yorker began investing some ink in the endeavor by announcing they’ll print a full-page puzzle in every issue of the print magazine.

The crossword puzzles, like the magazine’s longform journalism, fiction, and other work, live behind a metered paywall online. Readers who have not subscribed can view the newyorker.com home page, Goings On About Town listings, and a limited number of articles (including puzzles) per month; a digital-only subscription costs $100/year. The “Subscribe” page highlights the crossword, noting that every option includes access to “newyorker.com, including the online archive and crossword puzzles.”

Unlike The New York Times, which offers a standalone subscription to its crossword and other games, the only way to gain unfettered access to the New Yorker’s puzzles is to subscribe to everything. And, given that 80 percent of The New Yorker’s revenue is reader-generated, that’s exactly what the publication is hoping readers will do.

But can crossword puzzles really affect a news organization’s bottom line? There’s evidence to suggest the answer is yes. Publishers have found that the number of active days a reader has on their site is a telling metric for determining whether or not they’ll continue a subscription. Encouraging readers to develop a crossword habit may help. At The Wall Street Journal, for example, a team looking to increase subscribers’ active days found that playing a puzzle had a more dramatic impact on reader retention than other actions the team had been promoting to new subscribers, such as subscribing to an email newsletter or downloading the Journal’s app.The New Yorker’s puzzle has been getting rave reviews from the crossworld, er, crossword community. Rachel Fabi, a professor of bioethics who moonlights as a crossword reviewer and constructor, says it’s her favorite puzzle to solve, thanks to a diverse set of constructors, answers that send her down fruitful Wikipedia rabbit holes, and a lively, unstuffy style. (“Love that New Yorker puzzles can just clue ASSES as ASSES without any need to pretend like they’re talking about donkeys,” she wrote in a recent review.)

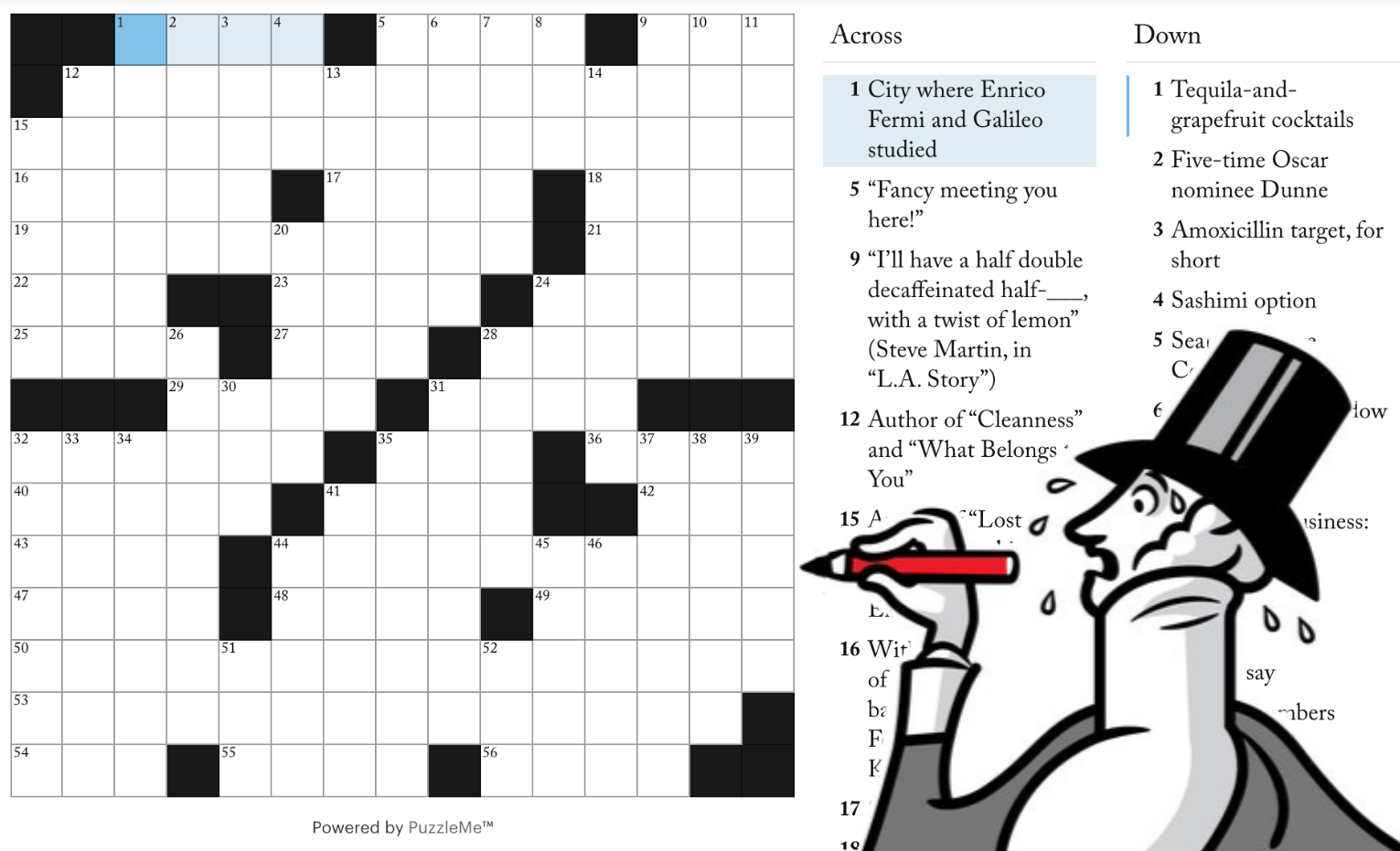

Unlike The New York Times and other crosswords, The New Yorker’s crosswords get easier with each passing weekday and are always themeless. (The hardest crossword — the type that has “Eustace Tilley” sweating bullets, as above — appears on Mondays, the easiest on Fridays. Something in the middle is published on Wednesdays.) They’re also seen as less concerned with catering to an imagined “average solver,” Fabi said.

“There’s been a lot of discussion in the crossword space about what clues or entries get rejected from the Times,” said Fabi, who has constructed for the Times and USA Today, along with indie outlets like Inkubator. “You’ll get a rejection from the Times saying ‘This is not something that the average solver will know,’ which carries with it this connotation that an average solver is a white man in his 50s. There’s an expectation that the person solving your puzzle looks like Will Shortz.”‘The New Yorker is willing to press those boundaries and reject that vision of the average solver,” she added. “There’s just a lot more diversity, both in the constructors but also in the clues and entries, in a New Yorker puzzle.”

The New Yorker’s Puzzles & Games Dept. is led by Liz Maynes-Aminzade, previously the magazine’s digital initiatives editor. I asked her about how The New Yorker’s quirky house style affects solvers, what other games they’re cooking up, and how her work fits into the magazine’s larger subscription strategy.

Read on for our full conversation, which has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

We launched the weekly crossword in April of 2018, and by the end of that year, it had developed a solid audience: not huge in terms of scale, but very engaged. In 2019, we added a second, easier weekly crossword, because a lot of people found our original crossword prohibitively hard. By then, the crossword had become a big part of my job: not just editing it, but working with our tech team and our partners at Amuse Labs to refine the product, for instance, by making it work better on mobile.

By that point, it seemed clear to me that puzzles and games were a bigger area of opportunity. Mike Luo, the editor of newyorker.com, and Pam McCarthy, The New Yorker’s deputy editor at the time, believed that, too, as did others involved with strategy and audience development. I took on the mantle of puzzles & games editor at the end of 2019, and I’ve been building out the department since then. Nick Henriquez, who began co-editing crosswords with me when David went on paternity leave, became our associate crossword editor (he splits his time between crosswords and our production department). And Andy Kravis joined as assistant puzzles & games editor last summer. We also now have three fact-checkers who share crossword-checking duties, a proofreader, and a handful of puzzle testers and “consultants” around the office.

As for where people play, this has changed somewhat since we launched. You can play in the New Yorker app, as you say, and a lot of our audience has migrated there in the past year; if you’re playing on a phone, the app offers a much better experience than a web browser. There’s more screen real estate, for one thing, and you can stay logged in [Ed. note: !] and save your progress.

I have no idea how many people solve the crossword in the magazine; that will probably remain a bit of a mystery. But I’d guess a significant number, since it’s a mix of old and new audiences: those who regularly solve online but prefer to do so in print, and those who primarily read The New Yorker in print, and discovered our crossword that way. One interesting data point is that 5-10 percent of our online crossword audience prints out each puzzle. That tells you how much some people prefer the experience of solving by hand.

We also get some funny emails when people are scandalized by clues. Someone wrote in objecting to a puzzle that had LUBE in the grid — clued as “Bedside-table supply, perhaps” — which she said had ruined her morning coffee.

Most New Yorker readers would find it a no-brainer, I think, that a more diverse group of constructors makes for a better and more fun puzzle. And I mean diverse in terms of race, gender, sexual identity, of course, as well as things like age and regional background. All those factors shape a constructor’s lexicon and frame of reference. And the appeal of a crossword is testing what you know, but it’s also learning new things. That strikes me as even more true of crosswords than other trivia-related games, where, often, you know it or you don’t. With a crossword, you can still “win” without knowing all the answers, and there’s a unique pleasure in revealing an answer by filling in the crossings.

We also digitized the great series of British-style cryptic crosswords that ran in the magazine in the 1990s; those are now playable online every Sunday. Because cryptics aren’t a big part of American culture, and have a higher barrier to entry — there are a lot of rules to learn — they haven’t found the audience of our American-style crosswords. Regardless, I think they’re a lot of fun, and we’ll likely keep them going once we run out of the ‘90s originals. Who knows, maybe we can turn a new generation of Americans on to cryptics.

Most of my energies right now are focused on a new game, which Andy and I have been working on for a while with our product team. It will launch later this year, and I’m pretty excited about it, but I probably shouldn’t say what it is. Sorry to be coy!

New Yorker crosswords are also relatively topical. We have a fairly quick turnaround from first draft to publication, so our constructors know they can be responsive to things in the news.

Above all, though, I think our constructors are what set our crossword apart. All ten of them are fantastic, and each one has a distinctive voice.

To the question of what kind of games appeal to New Yorker readers, I think your formula — language-related, culturally literate, and challenging — pretty much nails it.

Initially, we tried sharing The New Yorker’s word list with the constructors, but you can’t really expect someone who’s not a copy editor here to memorize all the quirks. Eventually, we explained the situation to The New Yorker’s copy chief, Andrew Boynton, who was very understanding. He gave the crossword a special dispensation to use standard spellings as needed. It was a big moment; I think our constructors were relieved.

I asked a few of our constructors for their favorites. Erik Agard cited Kameron’s clue “Beauty company?” (answer: BEAST). Liz named this clue of Anna’s as a favorite fill-in-the-blank: “‘__ the Way,’ Loretta Lynn song that ends with the line ‘I hope it ain’t twins again’” (answer: ONE’S ON). And Wyna Liu applauded this clue from Natan Last: “Awkward knee-jerk response to a waiter saying ‘Enjoy your meal!’” (answer: YOU TOO).