New York City is now the largest municipality in the country to implement ranked-choice voting. In a city where there are seven registered Democrats for every registered Republican, the primary election this month will almost certainly determine who takes citywide offices.

Here’s the rub for voters and the newsrooms catering to them. Ranked-choice voting is a bit complicated for the uninitiated. Ballots can be “exhausted.” Voters have the option of ranking several candidates — or they can cast their ballot for just one. The candidate leading after the first round of vote-counting may not, ultimately, be the winner. And the method can lead to some wacky political maneuverings, like two candidates for the same office endorsing one another.

With widespread mistrust in our democratic processes, covering election administration and explaining how, exactly, democracy works in the U.S. is increasingly important. Here’s how a handful of news organizations in New York are covering the new way to vote.

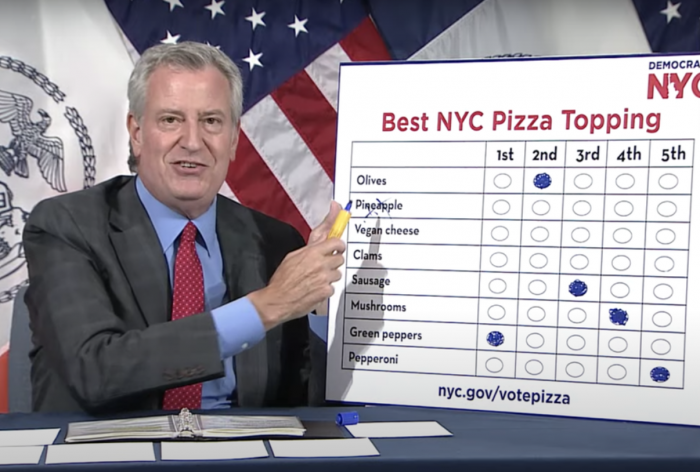

To explain how ranked-choice voting works, news organizations — and city officials — are wading into highly charged but ultimately nonpartisan debates. New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio, who knows that local media can’t resist a pizza-related story, ranked toppings to demonstrate how the process works in a press conference.

“A lot of people don’t appreciate green peppers enough,” de Blasio deadpanned. “I have southern Italian roots. Green peppers are a very big, important part of our life.” https://t.co/mZWD3hMa3G

— Sam Raskin (@samraskinz) June 10, 2021

What’s more NYC than pizza? How about bagels? To demonstrate how the ranked-choice process works, The Wall Street Journal pitted classic bagel orders against one another.

The interactive explainer shows how the worst-performing candidate is eliminated and their votes are redistributed to other viable candidates every round, until one candidate captures 50 percent of the vote. (The cinnamon raisin with jam and butter never stood a chance.)

Gothamist, meanwhile, turned to fictional rather than culinary inspiration. The digital news site, which has been part of New York’s public radio station WNYC since 2018, ran two “simulations” to show how ranked-choice voting works. The first pitted fictional mayors against one another and a second, in partnership with the New York Public Library, saw New York novels facing off.

What is your favorite book about (or featuring) New York City? Here’s how 6 of the 8 leading mayoral candidates answered. https://t.co/7fWt3wuRvs pic.twitter.com/9Aoxg8n8Z1

— Gothamist (@Gothamist) May 12, 2021

The Votes Are IN For Our Greatest Fictional Mayor of NYC Election & here’s how it all played out through ranked-choice voting https://t.co/BjmL5LLMIU pic.twitter.com/6m9P91tm2X

— Gothamist (@Gothamist) February 18, 2021

One news organization putting major resources behind getting New Yorkers ready to vote is The City. The nonprofit newsroom, launched in 2019, found that readers have a lot of questions about the election — and about using ranked-choice voting for the first time, in particular.

The queries ranged from basic (What’s ranked-choice voting?) to skeptical (Why are we even doing this?) to strategic (How can I optimize my ballot so that [Candidate X] doesn’t win?). To address them all, Rachel Holliday Smith, a reporter for The City, wound up writing two explainers.

Smith’s work is part of a larger effort at The City — called Civic Newsroom — to “encourage and inform engagement in local politics and the electoral process.” Although primary elections often determine the winning candidate, voter turnout has been dismal at the local level. (In 2017, just 15 percent of Democrats voted in the primary. In 2013, the last time there was an open primary for the mayor’s office, the number wasn’t much better: 20 percent turned out.) Smith, though, said the response from readers to The City’s call for questions and comments has been encouraging.

“In getting these questions from people, it’s really clear that, beyond just this election, people have a lot of questions about how civic life works in New York,” Smith said. “They’re asking, ‘What’s the deal with community boards? What are they? What do they even do?’ ‘What is the power dynamic between the state, the city, the federal government, and these hyperlocal offices?’ I think people are hungry for more journalism about civic life in general.”

The explainers have been published in English and Spanish on The City’s website and are available in audio form, too. Terry Parris Jr., The City’s engagement director, said voting guides have also been translated into Chinese and Korean for in-person distribution at the newsroom’s Voterfest events.

For the outdoor (read: Covid-safe) Voterfest events, The City chose three NYC neighborhoods with historically low voter turnout and partnered with community organizers. The partners included South Bronx Unite and Nos Quedamos in Mott Haven in the Bronx; the Brooklyn Public Library in Brownsville; and MinKwon Center for Community Action, APA VOICE and the Chinese American Planning Council in Flushing, Queens. The City, which has hosted other “open newsroom” events on housing and jobs, hopes to expand the civic series in the future.

“It is very much an experiment because it is only three neighborhoods,” Parris said. “But if we can start to figure out, ‘What are the practices?’ and ‘What are the materials and partnerships we need?’ and ‘How can we spread that into three other neighborhoods? And then six other neighborhoods?’ — then it becomes more efficient.”

As part of Civic Newsroom, The City also publishes weekly election news and information via newsletter and text message. The newsletter has about 5,000 subscribers and text messages go out to another 1,000 people. Parris said these initial signups will help shape the future of the Civic Newsroom after the current election wraps up.

“Civic engagement isn’t just voting and we hope to think about that as we move forward,” Parris said. “Voter mobilization is as much of a relationship with your community and audience as it is anything else. This is us making relationships and we want to continue the program [Civic Newsroom] and apply it to other aspects of city life.”

In 2020, new projects and entire newsrooms popped up to cover the ins and outs of voting. Experts urged journalists to responsibly cover election administration — including informing the electorate that, given the close race and practicalities of vote counting during a pandemic, declaring a winner in the presidential race could take weeks.

Now, the election in New York City is not the first to use ranked-choice voting. Maine — and a handful of cities, including San Francisco — have been serving as a laboratory for democracy in recent years. But there’s about 1.3 million people living in the state of Maine … and roughly 8 million in New York City. Even with less-than-stellar turnout, that’s a lot of ranked-choice ballots to tabulate. (At least the city has approved software for the job; special elections in Queens earlier this year had to be counted by hand.)The city’s Board of Elections will release initial, unofficial results on election night that reflect first-choice votes. There are 15 candidates running in the mayoral election alone, so there’s a very good chance that no one candidate will capture the majority of votes right away. (Ranked-choice voting is sometimes called instant-runoff voting for this very reason.) Election officials won’t begin to compute additional ranked-choice voting rounds until a week after election day.

“We’re trying to do as much reporting as possible to prepare people for that,” Smith said. “It’s not going to be over on June 23. It’s going to be weeks, probably, until we have a solid answer.”

Gothamist is taking a similar approach. It ended its guide to ranked choice voting with a plea for New Yorkers to, please, be patient.