Last week, Ed Zitron wrote an important piece on coordinated online attacks against reporters. His primary argument is that newsrooms still don’t understand the nature of the culture war they’re sending their reporters out into each day. When their employees are the subject of bad faith networked harassment campaigns, they frequently fail to protect their reporters or, more troublingly, they sometimes punish their staffers for attracting perceived “controversy.”

News organizations often address bad faith attacks on reporters by repeating the language of the attackers, in part, because they’re worried about looking “impartial.” What they ought to do, he says, is dismiss the attacks outright for what they are: propaganda intended to delegitimize their institutions.

Zitron argues that big news organizations “need to invest significantly in exhaustive, organization-wide education about how these online culture war campaigns start, what they do, what their goals are (intimidating critics and would-be critics) and are not (their goals are not reporting, or correcting facts, for example), the language and means they use to execute, and how they use the newsroom against itself.” Only then, he writes, can newsrooms respond “from a position of power.”

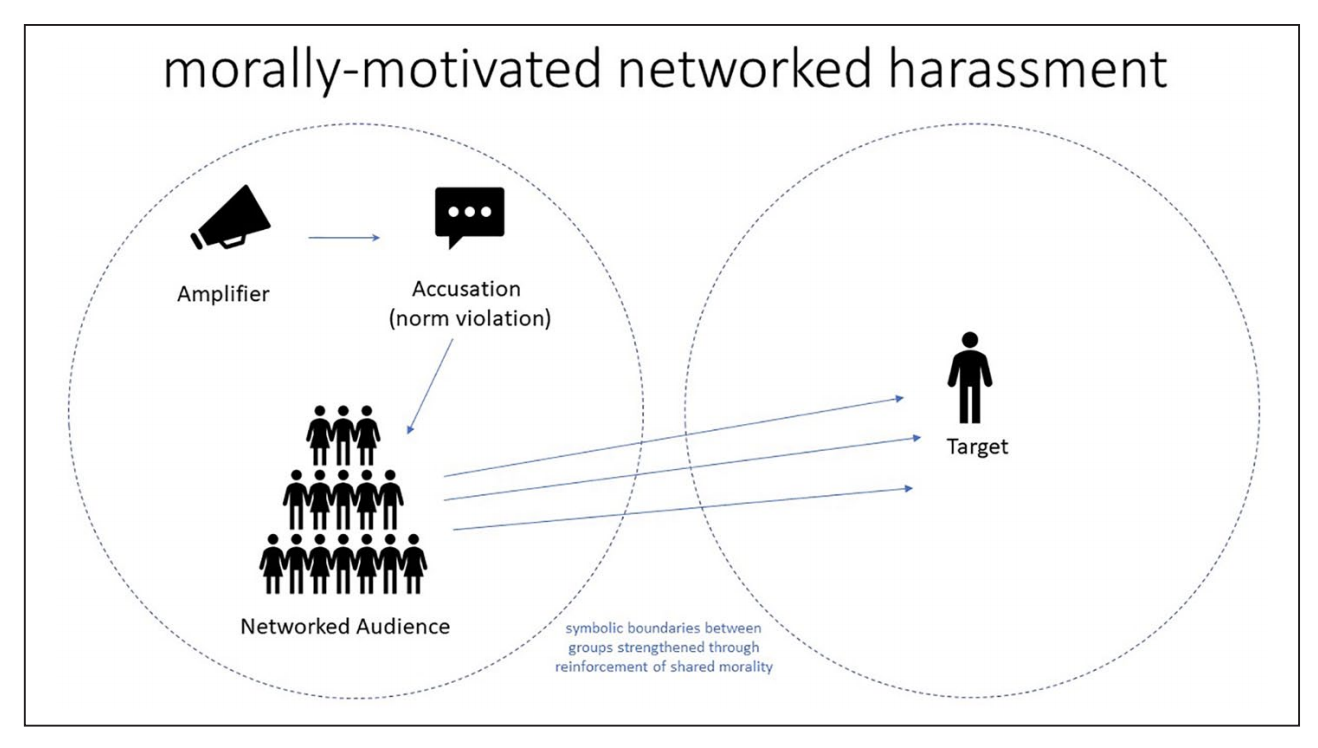

Zitron’s post reminded me of a fascinating paper I read recently by UNC associate professor Alice E. Marwick on “morally motivated networked harassment.” The paper offers exactly the kind of detailed explanation of how and why online harassment takes place at scale that newsrooms are lacking. Marwick focuses on a specific variety of online harassment called “morally motivated networked harassment,” which is the type that’s most prevalent in arguments about politics, cancel culture, and media bias.

Networked harassment is when a large audience descends on a person and overwhelms them — the speed and volume are what do the most damage. But, as Marwick notes, the larger audience of harassers is usually convened (sometimes unwittingly, often purposefully) by an amplifier, which is usually a high profile or well-followed social media account or community. The important function of the amplifier is that they tend to take a person’s comment or idea and move it from the author’s original context and audience and into their audience (this phenomenon is called context collapse).

This process is particularly effective at generating conflict at scale. Marwick describes what it looks like quite well:

For instance, a progressive activist advocating deplatforming alt-right influencers might be labeled “anti-free speech” or “censoring” by right-wing network participants, while members of a left-wing network view them differently. In this case, the two networks have different priorities, values, and community norms. However, the context collapse endemic to large social platforms allows for networks with radically different norms and mores to be visible to each other.

Networked harassment is particularly thorny to navigate because it’s not always easy to enforce. As Marwick notes, most platforms’ Terms of Service define harassment in a different, more traditional context (one individual repeatedly harassing another) and tend not to take into account the amplifier factor. Here’s how one person Marwick interviewed described the disconnect as it relates to tech platform enforcement:

The Twitter staff might recognize it as harassment if one person sent you 50 messages telling you suck, but it’s always the one person [who] posted one quote tweet saying that you suck, and then it’s 50 of their followers who all independently sent you those messages, right?

Put another way: serial amplifiers — especially the savvy ones who don’t themselves harass but signal their disapproval to their large audiences knowing their followers will do the dirty work — tend to get away with launching these campaigns, while smaller accounts get in trouble. A good amplifier knows how to create plausible deniability around their behavior. Often they say they are “just asking questions” or “leveling a fair critique at a person or public figure.” Occasionally, this is true, and individuals inadvertently kick off networked harassment events with good faith criticisms. Sometimes, people with big accounts forget the size of their audience, whose behaviors they can’t control. These social media dynamics are messy because they vary on a case by case basis.

Still, morally motivated networked harassment is extremely common and intense. Marwick’s paper suggests that’s because the tactic “functions as a mechanism to enforce social order.” And the enforcement tool in these instances is moral outrage.

“A member of a social network or online community accuses a target of violating their network’s norms, triggering moral outrage,” she writes. “Network members send harassing messages to the target, reinforcing their adherence to the norm and signaling network membership.” As anyone who has spent time online knows, morally charged content performs better online. It resonates widely and provokes strong responses among all humans. “As a result, people are far more likely to encounter a moral norm violation online than offline,” Marwick notes. This is partly why spaces like Twitter, where different audiences interact easily, feel especially toxic.

What I appreciate most about Marwick’s paper is that it wrestles with the complexity of this type of networked harassment. In her studies, Marwick finds that “networked harassment is a tactic used across political and ideological groups and, as we have seen, by groups that do not map easily to political positions, such as conflicts within fandom or arguments over business.” Everyone across social media is constantly signaling affiliations with their desired groups. And each of those groups are trying to enforce a social order of their own based on their preferred moral codes. Dogpiling abounds.

Marwick also demonstrates that the subjects/circumstances with the potential to trigger harassing incidents are almost unlimited. For the paper, she spoke to people who’d been targets of harassment campaigns for the following reasons: tweeting, “Man, I hate white men” in response to a video of police brutality; criticizing the pre-Raphaelite art movement; refusing to testify in favor of a student accused of sexual harassment; banning someone from a popular internet forum; criticizing expatriate men for dating local women; and celebrating the legalization of gay marriage in the United Kingdom by posting gifs of the television show “Sherlock.”

It is important to recognize the universality of this phenomenon, in part so that we don’t fall into amplifier modes ourselves. But we also cannot confuse the fact that anyone can be the subject of networked harassment with the fact that morally motivated networked harassment isn’t always evenly distributed.

Harassment, Marwick argues, “must also be linked to structural systems of misogyny, racism, homophobia, and transphobia, which determine the primary standards and norms by which people speaking in public are judged.” She writes that women who violate traditional norms “of feminine quietude” experience disproportionate amounts of harassment which is linked to their gender. She deems these characteristics “attack vectors,” another word for vulnerabilities that increase the likelihood of online harassment. For example, while a nonbinary individual might be harassed over comments about anything, their nonbinary status will frequently become what she calls an “attack vector.”

Though Marwick’s paper is not about the harassment of reporters, much of the harassment leveled at journalists is conducted via morally motivated networked harassment. Just as important: the frequent, complex, and extremely varied kinds of harassment that Marwick describes is essentially the environment that newsrooms ask their reporters to go out into each day.

Not only are reporters participating in these online ecosystems when they’re promoting their stories or looking for stories, but they are also frequently covering the culture war arguments that take place on the platforms. By writing about or commenting on the online culture wars, reporters, wittingly or not, become a part of those culture wars. Similarly, news organizations influence and shape some of these fights, whether or not they intend to. The nature of the social web makes it incredibly difficult — if not completely impossible — for the press to be some kind of invisible bystander.

The fact that many news organizations think that they can engage or even merely observe and document these environments — and not also influence them — leads me to believe that newsroom leaders still don’t understand the complex dynamics of social media. Many leaders at big news organizations don’t think in terms of “attack vectors” or amplifier accounts — they think in terms of editorial bias and newsworthiness. They don’t fully understand the networked nature of fandoms and communities or the way that context collapse causes legitimate reporting to be willfully misconstrued and used against staffers. They might grasp, but don’t fully understand, how seemingly mundane mentions on a cable news show like Tucker Carlson’s can then lead to intense, targeted harassment on completely separate platforms.

And yet these newsroom leaders privilege stories that touch divisive, morally charged issues. They want reporters to cover controversial subjects and the most active and inflammatory communities because the emotional charge that makes these people and spaces so volatile also makes for a good, sharable story — for news.

I’m not suggesting newsroom leaders don’t think the internet is a dangerous, often toxic place. A number of the people I’ve met who run or have run legacy newsrooms are reflexively skeptical of social media. Most of them didn’t come up in newsrooms dominated by social media and lament “the discourse” as a liability for their staff and institution. I’ve been at drinks with one or two of these people as they’ve told me that they’ve given up on Twitter altogether (interestingly, they used the same phrase: “I don’t do Twitter anymore”), citing it as a distraction from the real work of journalism. Sure.

But what I think they miss is that, for better or worse, “the discourse” is part of the work these days. In many cases, it is the context into which the work is dropped.

I don’t mean to provoke the “Twitter is not real life” crowd by suggesting that newsrooms need to make Twitter the assignment editor (please don’t do this!). I also don’t think that the most impactful journalism needs to come from the Extremely Online. Great journalism that speaks truth to power and has real world impact doesn’t need to have anything to do with an internet connection. But the larger cultural forces and conversation that surround that work — how it will be interpreted, weaponized, distorted, and, perhaps, remembered? That conversation will happen in these online spaces. A piece of shoe leather investigative reporting that never mentions the internet will eventually find its way into a culture war fight online and will likely be used to further somebody else’s propaganda campaign. Likely, this will involve discrediting the reporter who produced it.

This is where “I don’t do Twitter” (or insert platform here) becomes a liability. Not because Twitter is some great space for conversation or because being connected to it all day is the best use of a newsroom leader’s time and energy. But because the leader has no good sense of the environment their organization is dropping a reporter or a story into. Their ignorance is not a virtue, but a liability — for their staffers and for their organization at large.

More commonly, legacy newsroom leaders will graze on social media. They’re extremely busy running large institutions through chaotic news cycles and so they dip in and get a sense of the conversations from the social media bubbles they’ve created. They tend to have a vague sense of online dynamics, but it often lacks nuance. I’d argue this posture is the most dangerous, as it is the one most likely to overreact to bad faith attacks from trolls. They see outrage building, realize it is pointed at their institution, and they panic. They panic, in part, because they don’t understand where it’s coming from or why it’s happening or what the broader context for the attack is. This is when leaders make decisions that play into the hands of their worst faith critics.

If you run a newsroom — of any size — you need an internet IQ of sorts. Unfortunately, this kind of savvy is only really gained through experience or study. I spent a long time talking about Marwick’s paper because it’s an illustrative example of how the dynamics of online spaces and conversations are complicated. They require study and expertise, especially if you plan to navigate them. But if you spend real time in these spaces, you start to instinctively understand what’s happening.

Is internet savvy the most important skill an editor in chief ought to have right now? I don’t know. But currently, the skillset seems like an afterthought, especially in larger institutions. That’s a mistake. So much about newsgathering — talking to sources, framing stories, even managing writer personalities — is about developing an intuition and calibrating your sense of proportion. Is this person lying to me? Is this story an outlier or indicative of a more universal experience? The same thing is true about the navigating social media. As The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson mentioned this week, it’s critical to develop the right “thickness of skin” for the internet. And there’s just no good shortcut.

Critical 21st century skill: Developing the right “thickness of skin” on the Internet—that is, understanding when to listen to critics who have a point, but also how to not care when bunch of crazy people are screaming at you online https://t.co/vUY6sroGfu

— Derek Thompson (@DKThomp) June 15, 2021

If you’re interested in looking at the kind of policies that come out of a newsroom run by people who instinctively understand the internet, take a look at Defector Media’s harassment policy. The company covers expenses for the harassed, provides alternate housing if necessary, offers paid time off, works with law enforcement, provides legal help, and even provides a proxy “who can temporarily manage a targeted employee’s social media accounts.” The big difference, beyond the benefits, is that the organization’s leaders see harassment as an unfortunate and often difficult to avoid byproduct of reporters doing their job in a hostile environment. They trust their employees and stand by their work. They don’t get easily spooked by random jabronis trying to drag the site into a culture war argument and rashly suspend or fire a reporter. But they also instinctually know when shit is getting out of hand.

I get that navigating online bullshit is hard. I wish none of these words I wrote were necessary. I wish journalism wasn’t fully intertwined with commercial advertising platforms that connect millions of people with each other at once. I wish we didn’t outsource our political and cultural conversations to these commercial advertising platforms. I wish newsroom leaders and reporters could completely ignore these spaces and focus on a pure version of journalism. I don’t like this system any more than they do. But it’s the one we’ve got. Newsrooms don’t understand the internet they send their journalists onto. That needs to change.

Charlie Warzel writes Galaxy Brain, a newsletter about the internet, where this post originally appeared. Subscribe here. He was previously an opinion columnist for The New York Times.