In early January 2020, the BBC reported about a new “mystery virus” in Wuhan, China. Since then, news organizations around the world have learned important lessons from covering Covid-19 that could become valuable for how they cover the climate crisis.

Never in the history of modern news journalism has a science story — the story of a new pandemic, its prevention and treatment — dominated the news agenda for as long as Covid-19 has. When I asked science journalists if they could think of any precedent, some mentioned the space race between the former Soviet Union and the U.S., from the “Sputnik shock” in 1957 to the moon landing in 1969. While the space race did garner enormous media attention, its effects on everyday life can’t be compared to those caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, and it didn’t dominate the worldwide news agenda as much as Covid-19 has.“The last 18 months have been a step change for our newsroom,” said Sven Stockrahm, science editor of German news organization Zeit Online. “Of course, our workload has been staggering, but we are delighted to see how normal it has become for all teams in our newsroom to first consult with the science desk before publishing a story that deals with aspects of Covid-19.” The degree of interdisciplinary collaboration with the science desk is new, and it could prove a model for how news organizations cover the climate crisis.

Today, news reports about the climate crisis primarily come from a newsroom’s science, politics or economics desk. A few news organizations already understand, though, that the climate crisis is more than a beat or a topic — it poses urgent questions that affect all sectors of society. Based on this understanding, journalistic coverage of climate change needs to involve all teams of a newsroom, including its culture, finance, real estate, lifestyle, fashion, health, and sports journalists.

When sports journalism mentions the financial aspects of a team, a transfer, or a tournament, nobody would be surprised to see “business journalism in the sports section.” Climate journalism needs to become just as integrated in every vertical.

“We are not learning the lessons that the Covid-19 pandemic taught us, where we have a global crisis and the entire newsroom mobilizes to cover that crisis,” said Emily Atkin, environment reporter and editor of the newsletter Heated, in a recent interview with CNN’s Brian Stelter. “We understand that this infiltrates every single area of our life.” She continued: “There is no excuse for a reporter today who doesn’t understand the basic science of Covid-19. Why is it not the same for climate change? Everyone should be a climate reporter. And if you are not a climate reporter right now, you will be.”

What are the other potential lessons from covering Covid-19 for covering the climate crisis?

For journalism about Covid-19 to be effective, readers, viewers, and listeners need to know some basic scientific facts and metrics of the pandemic: How does contagion via aerosols work? What is a national vaccination rate and what do the regular updates on R values and “7-day incidence rates” mean?

News organizations have established at least some of these basic facts and metrics within only a few months. They achieved this through consistent repetition, easily visible explainer boxes in their texts, and prominently placed data modules on their sites. The pandemic has also brought about some outstanding interactive journalism, explaining the core facts of Covid-19 and its transmission.

For journalism to more effectively inform about the climate crisis, news organizations equally depend on their audiences having acquired basic climate literacy.

Learning from Covid-19 journalism could mean that news organizations pick only a small set of key metrics for the climate crisis and emerging solutions, such as the global CO2 ppm value and the percentage of renewables in their own country’s national energy mix, and then keep repeating, explaining, and updating these few metrics regularly. Bloomberg Green already experiments with embedding a consistent set of climate data in all its texts. The Guardian publishes global carbon dioxide levels in its weather forecasts.

An audience’s climate literacy over time could be tested with reader surveys or, less intrusively, climate quizzes such as the ones produced by the Financial Times, the The Washington Post, or, in a localized version, by Boston’s public radio station WBUR.

Some other potential lessons from covering Covid-19 for covering climate change are more tangential: During these last 18 months, journalists have gained valuable experience in covering the often conflicted relationships between governments and their own scientific advisors, as well as public disputes between reputable scientists.

With climate change becoming the central theme in some national election campaigns, and with debates about the Green New Deal in the U.S. or the European Green Deal taking center stage, many journalists’ recent experience of reporting on the tension between politics and science during the pandemic should prove valuable again.

When asked what further changes he would hope for in his newsroom after 18 months of covering Covid-19, German science editor Stockrahm said, “I would hope for a greater appreciation of the fact that questioning science is a core part of science. It is a misunderstanding of science when journalists primarily demand definitive answers from scientists or from us science journalists.” But this appreciation of scientific disagreements shouldn’t be confused with a dismissal of science itself. As a large-scale analysis of roughly 100,000 English-language digital and print media articles on climate change has shown, journalists often understate just how much scientific agreement there is on climate change and its human-made causes.

International surveys by Pew, the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, and the United Nations show broad public acknowledgment of the risks of global warming in most countries, with the U.S. typically ranking lower in the acknowledgment of climate risks than the UK, France, or Germany. In a Reuters Institute survey last year, 56% of U.S. respondents said climate change is very or extremely serious. In a 2019 Pew survey, 62% of U.S. respondents said global climate change is a major threat. And in a survey by the United Nations earlier this year, public belief in the climate emergency in the U.S. was at 65%, compared to 81% in the U.K. and Italy and 77% in France and Germany.

But journalists don’t necessarily need to segment their audiences into the majority that acknowledges climate change and the minority that doesn’t.

The psychologists Anna Klas and Edward J. R. Clarke suggest a more nuanced approach. When communicating about climate change, the two recommend factoring in the specific beliefs, values, identities, and political ideologies of six different groups of opinions on climate change: The alarmed, the concerned, the cautious, the disengaged, the doubtful and the dismissive. Yale University’s Program on Climate Change Communication refers to these six different groups as “Global Warming’s Six Americas” (take the quiz to see which group you fall into).

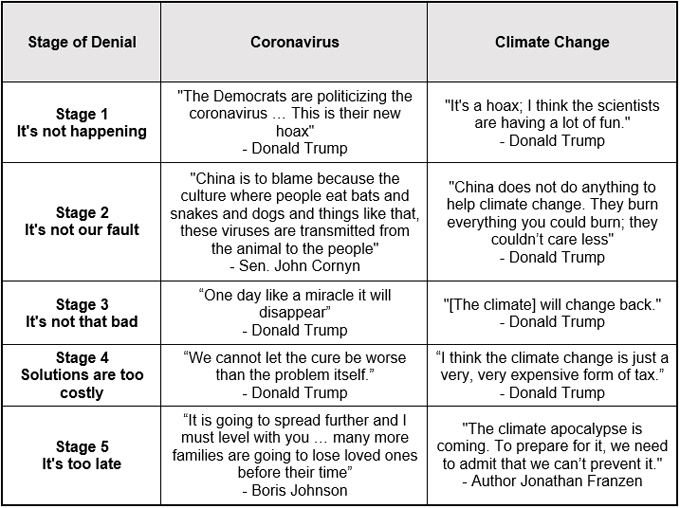

Environmental scientist Dana Nuccitelli has also identified five similar stages in which the outright denial of Covid-19 and the denial of climate science both unfold. Here’s his table:

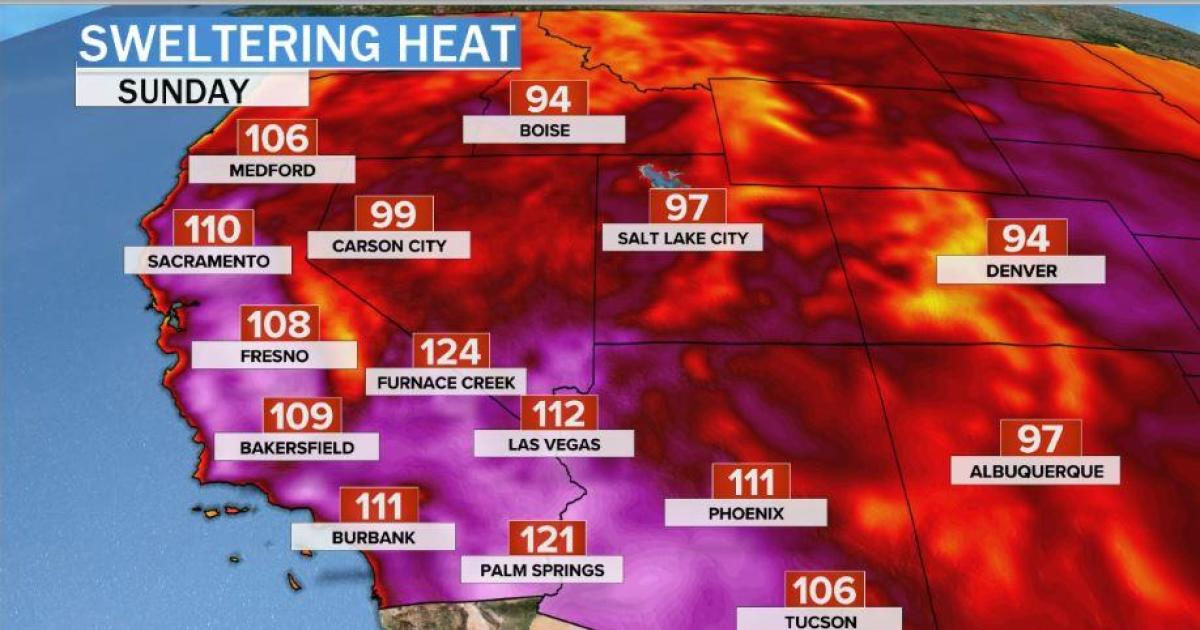

Another instructive similarity between covering Covid-19 and the climate crisis is that both crises are mostly being experienced locally but can only be overcome globally. The two crises are not only connected through the loss of biodiversity and animal habitats, which leads to an increase in zoonotic diseases, but both crises also reveal global injustices and the disparities between rich and poor countries.

Parallels between covering Covid-19 and the climate crisis have their limits, though. The most obvious difference between the two is that the risks from the climate crisis, and the necessary changes required from us to address it are far larger than what is required from humanity to overcome Covid-19.

Another key difference is the time horizon of the two phenomena. One day, we may be able to look back on Covid-19 as a challenge that we have overcome. For the climate crisis, the assumption is that while humanity still has a chance to stabilize the climate, nobody alive today will see the end of the challenges posed by human-made greenhouse gases we have already emitted into the atmosphere. For journalists, this is a difficult reality to convey.

Susan Hassol, a climate change communication expert, and Michael Mann, a climatologist and bestselling author, warned in 2017 that doomsday scenarios are as harmful as outright climate change denial. Both can lead to the disengagement of readers and viewers. The Yale Center for Environmental Communications recommends instead to rigorously cover the challenges of the climate crisis while also presenting credible solutions to them.

Especially during the early months of the pandemic and in countries where vaccines and masks were available, there was a list of practical things everyone could do to contain the pandemic: Wear masks, wash hands, keep distance, and, eventually, get vaccinated. The pandemic also had its early heroes, healthcare workers around whom a country could jointly experience important moments of appreciation and reflection.

The climate crisis, by comparison, is mostly missing such collectively agreed sets of behaviors and gestures. Compared to the commonly used metrics of the pandemic, such as the numbers of people tested, infected, hospitalized, or vaccinated, most news organizations are still missing a similarly small set of established key metrics for covering the climate crisis. Having a set of commonly understood metrics of climate change itself and of the key measures to mitigate the climate crisis could give readers much-needed context and allow them to track the development of a story over time.

When dealing with climate science denial, with so-called “doom-ism, or with targeted misinformation directed at their journalism, news organizations should also factor in that the vested industry interests in undermining climate science and in delaying mitigation actions are far greater than those in preventing measures against Covid-19.

For news organizations that want to reach young audiences, Covid-19 and the climate crisis each have risk profiles that are virtually mirror-opposite from each other in how they affect different age groups: While older people are at much greater risk from Covid-19 than young people are, young people face much greater challenges and potential hardships due to climate change in their remaining lifetime than older people do.

The different risk profiles and time horizons of the two crises may be reasons why most governments have been far more responsive to the Covid-19 pandemic than to the climate crisis. In a typical four- or five-year election cycle, most politicians still treat the climate crisis as something future politicians should deal with. They’d hurt their chances for re-election if they didn’t address the pandemic immediately.

Two leading experts and editors of a new research handbook on climate change communication, David Holmes and Dr. Lucy Richardson from Australia’s Monash University, have pointed out that while many politicians identify with climate denial lobbies and don’t trust climate science, they often trust the medical profession as it is tied to major campaign infrastructure known as “the healthcare system.” From the perspective of journalistic audience strategies, the strong resonance of health themes could then also speak for presenting the climate crisis more strongly as the enormous health challenge it already is.

Overall, journalists should feel encouraged by one finding of the 2021 Reuters Digital News report: during this last year of consistently covering the pandemic — a very complex and often frightening topic — trust in the news has grown worldwide, on average by six percentage points, bringing levels of trust back to those of 2018.

For news organizations, there could hardly be a more direct path toward being relevant to young readers, viewers, and listeners than to start covering the climate crisis at least as intensely as they covered Covid-19.

Wolfgang Blau is currently a visiting research fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, studying the intersection of journalism and the climate crisis. Prior to that, he was the global COO and president, international, of Condé Nast.