In the last year in the city of Atlanta, the story about “water boys” — teenagers who sell water at intersections — has become a hot-button issue.

I started out by reading the coverage on this topic in the city’s flagship newspaper, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Those stories often mentioned crime. “The issue of ubiquitous youths selling water at Atlanta’s intersections and highway exit ramps has become a tale of society cracking at the fringes,” one columnist wrote.

When the Atlanta City Council “passed a resolution calling for a feasibility study into whether the city should start a water business that could formally employ the water boys,” the Journal-Constitution’s editorial board wrote, “The city’s plan has potential to increase the already-powerful financial incentive that motivates the water sellers who hustle hard on city streets … given the steep spike in homicides that has taken hold over our city, it is hard to believe that developing an improved business model for a troublesome practice should be at the top of anyone’s to-do list.”

A nonprofit news outlet called Canopy Atlanta, however, took a different tone. In a story about “Baby D,” a water boy in the West End neighborhood, freelance reporter Gavin Godfrey, who won an Atlanta Press Club award for this story from October 2020, wrote:

A homeless man approaches carrying a 24-pack and a bag of ice over his shoulders. It’s Baby D’s re-up. The man drops the goods on the ground. Baby D hands over $3 and tells him, “Thank you, Unc,” short for Uncle. It’s a term of endearment given to anyone older than the boys. He’s making a killing today because, thanks to the cheap labor, he hasn’t needed to leave the spot yet.

Before he drove away, Baby D told Todd that he’ll most likely keep selling water. It’s easier and safer than some of his previous gigs. “I used to steal cars,” he admits. “If they stop this, then I’m going back to doing what I used to do.”

The story is filled with statistics and original photos of the main character; it’s clear that Godfrey spent lots of time with Baby D to get to know him. These are the types of stories that Canopy Atlanta strives to produce: ones that are impactful, relatable, and told for Atlantans by Atlantans.

Atlanta, which is 52% Black, is “the number one city for income inequality in America,” according to the Atlanta Wealth Building Initiative, an organization that seeks to close the city’s racial wealth gap. The median household income for a white family in the city is $83,722, AWBI found, compared to $28,105 for a Black family.

Canopy Atlanta is a nonprofit community news project that was started in 2020 by a group of around 25 journalists in Atlanta who were disappointed with the state of the city’s current media landscape. The group thought local media wasn’t diverse enough and it wasn’t always responsive to the people it was supposed to serve, said Sonam Vashi, one of Canopy’s six co-founders and its operations director. (There are currently no paid, full-time staff members, though Vashi said they’re on track to add paid staffers next year. Four of the co-founders, including Vashi, make up its core team of directors while the other two cofounders sit on the board of directors. They don’t take a salary.)

“A lot of us were reporters who felt like we were not doing what we came into this business to do,” Vashi said. “Community engagement can still be like a checkbox for a lot of media outlets, rather than the framing through which we look at everything. The biggest difference with Canopy is that we’re participatory and collaborative with the people that we cover.”

Canopy Atlanta’s model is just one of the recent approaches we’ve seen in trying to get community members involved in local journalism. In the past, McClatchy has launched community-funded reporting labs to focus on single issues and community advisory boards for its papers’ opinions sections. In 2016, Berkeleyside announced its plans to offer a direct public offering so its readers could also become its owners. A few weeks ago, I wrote about a weekly newspaper in Nebraska that turned its back room into a liquor store because its community didn’t have one.

Each Canopy Atlanta issue focuses on a different Atlanta community. In selecting the neighborhoods to cover, Canopy’s team thinks about which communities are underserved by other news outlets.

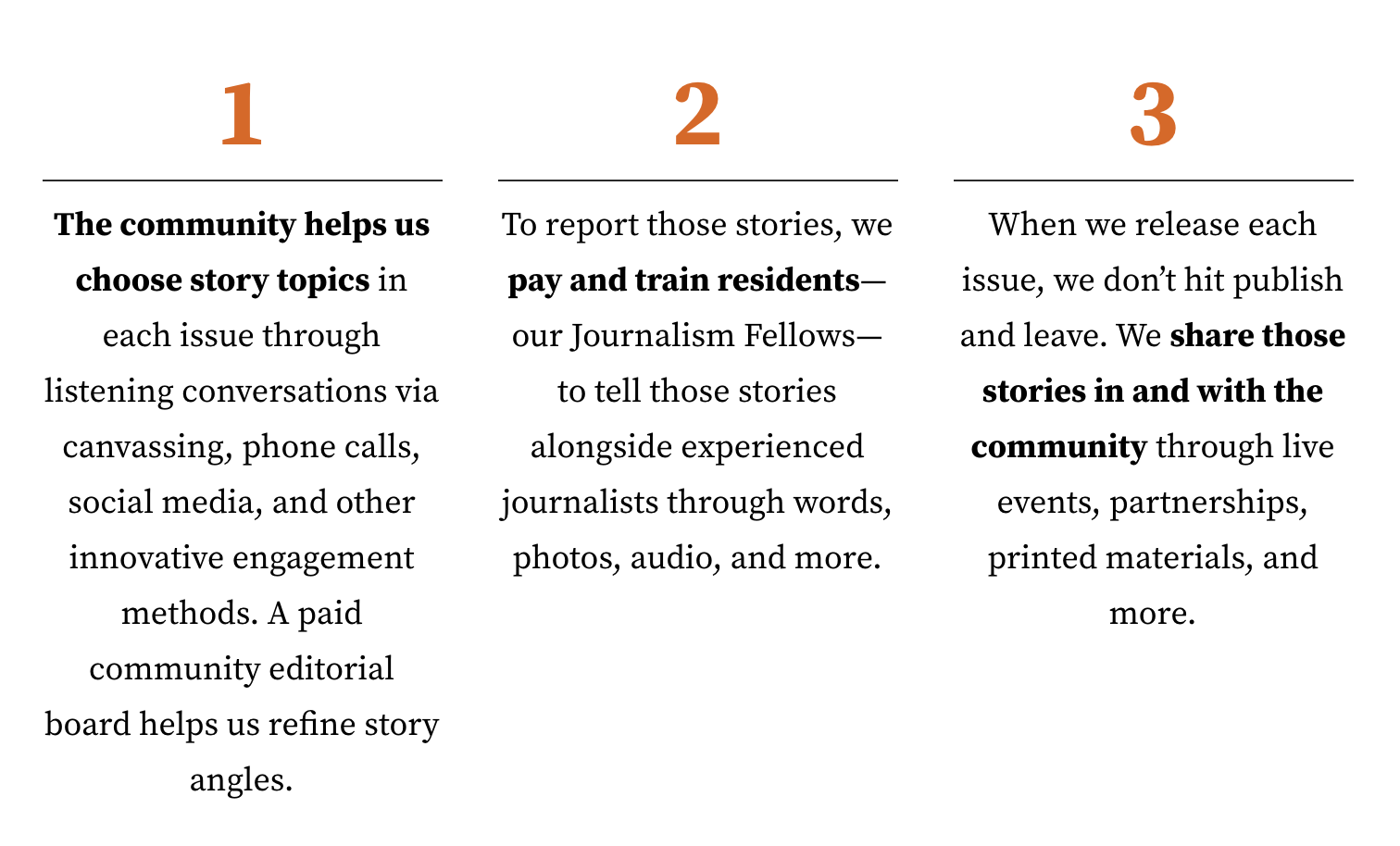

Once a community is selected, Canopy has a three-stage process. First is the community engagement strategy, which identifies people who are ambassadors for the neighborhood and looks at how information is already being shared in the community. The listening phase consists of canvassing, phone banking, and other methods to get a mass of responses about the types of issues the community wants covered. A community editorial board, made up of residents who apply to their positions and chosen by the core team of directors, helps sift through those responses and determine story angles.

Canopy also selects a class of fellows — usually either early-career journalists or longtime residents of the area with journalism-adjacent skills — to help produce the issue. Canopy’s cofounders and guest mentors — usually seasoned journalists in Atlanta — hold a six-week training program to teach the fellows about community journalism. The training teaches community members that anyone can be a journalist, and that their experiences are an asset, not a hindrance.

“We’re super-charging what a really good reporter does,” Vashi said.

The fellows then either work on their stories individually or pair up with experienced journalists to complete them. (The fellows and more experienced journalists are paid the same amount.) Once the stories are ready for publication, the team comes up with engagement strategies and events to get them out there.

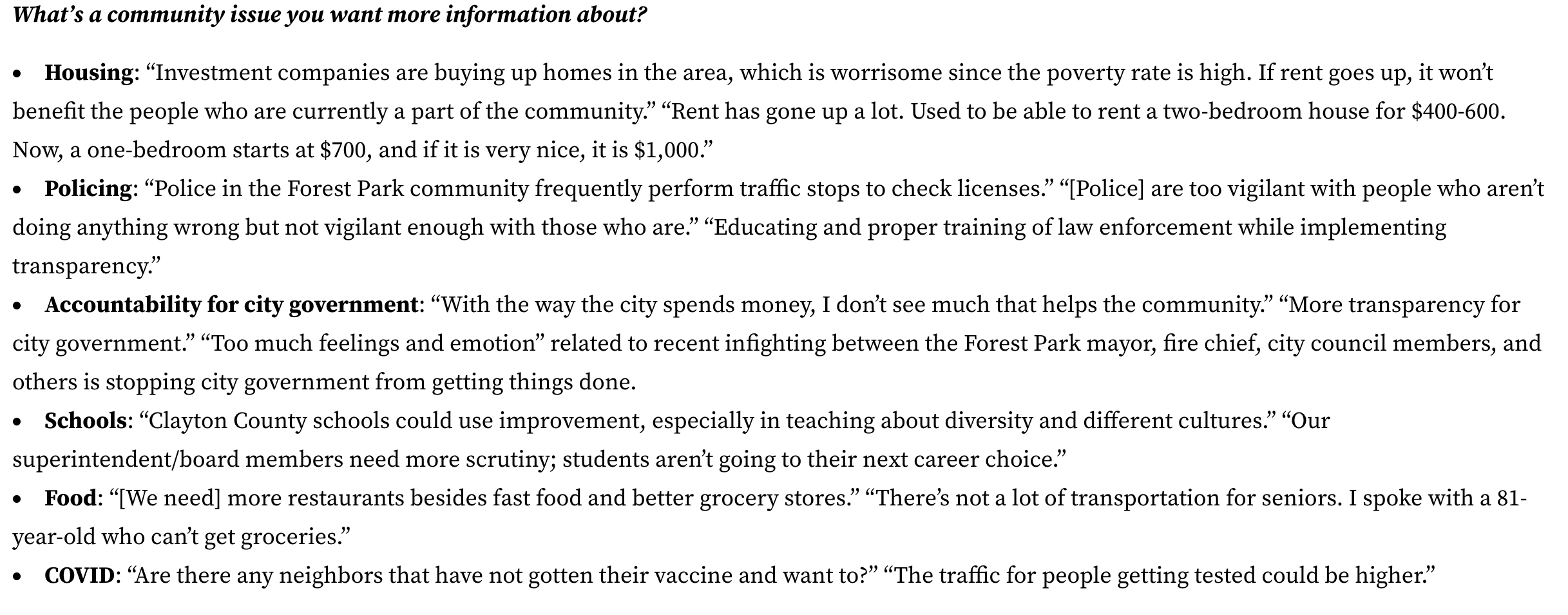

The Forest Park issue is currently in production, so the landing page shares Canopy’s findings from its listening phase.

“Our audience is really Metro Atlanta for the stories that we tell,” Vashi said. “In terms of the communities that we’re specifically training to access information to be journalists, we serve Black, brown, working class Atlanta or the specific community that we’re working in.”

Canopy is funded mostly through foundations, but also gifts, sponsorship and individual donations. It’s also looking into launching a membership program later this year. Its major donors include Mailchimp, The Kendeda Fund, United Way of Greater Atlanta, NewsMatch, and the Emory Philanthropy Lab. Canopy also collaborates and partners with other publications that are interested in Atlanta; the water boy story, for instance, was co-published with Atlanta Magazine and partially funded by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

“When we talk about building trust, I always feel like we’re talking about, [for instance], Trump supporters who call people fake news — that’s the kind of person centered in the larger conversation about rebuilding trust,” Vashi said. “[But] we think about people who never had trust in journalism in the first place. Our theory about how you build trust in information is to help people access it on their own.”