Writers Daisy Alioto and Kyle Chayka are known for their work on aesthetics and the internet: After its initial publisher fell through, Alioto self-published a longread essay entitled “What is Lifestyle?” looking at how we live has been affected by the internet; Chayka writes a weekly column for The New Yorker about digital culture. Sitting at home, during the pandemic, they were both spending a lot of time online. So, almost a year ago, Chayka and Alioto started Dirt, a Substack newsletter on these online habits — streaming incessantly and falling down internet rabbit holes. Sent several times a week, it talks about TV shows, movies, and the aesthetics of the internet — the “avant-garde of digital content,” in Chayka’s description.

Dirt has published pieces on YouTube desk tours; dressing like a Pokémon trainer; having lots of tabs open on your computer; and what the Sims can teach us about grieving. The publication recently hosted a Discord session where everyone watched the 1995 Japanese animated musical “Whisper of the Heart.” A T-shirt collaboration is in the work, as are TikTok essays — i.e., essays that will run on TikTok. “Dirt is like an afterschool activity club,” Chayka said.

Dirt is also completely free to read. It has no subscriber-only paid level and doesn’t solicit donations from readers. It pays its writers a $500 fee for each 500-word dispatch. Chakya and Alioto didn’t get an an advance from Substack. Instead, Dirt funds itself with the sale of non-fungible tokens, or NFTs.

No, wait, come back! Really quickly: An NFT is a unit of data stored on a digital ledger, or blockchain, the technology that underpins cryptocurrencies. “Conceptually speaking,” Chayka said, “NFTs are just a way of making multimedia on the internet a scarce commodity.” A piece of code is attached to a digital file and acts as a certificate of authenticity and scarcity. A real-life parallel might be prints of a piece of art: You can have one edition or more. It’s the code that’s traded when an NFT is sold; anyone can still use the image or video or other digital asset that the code is attached to.

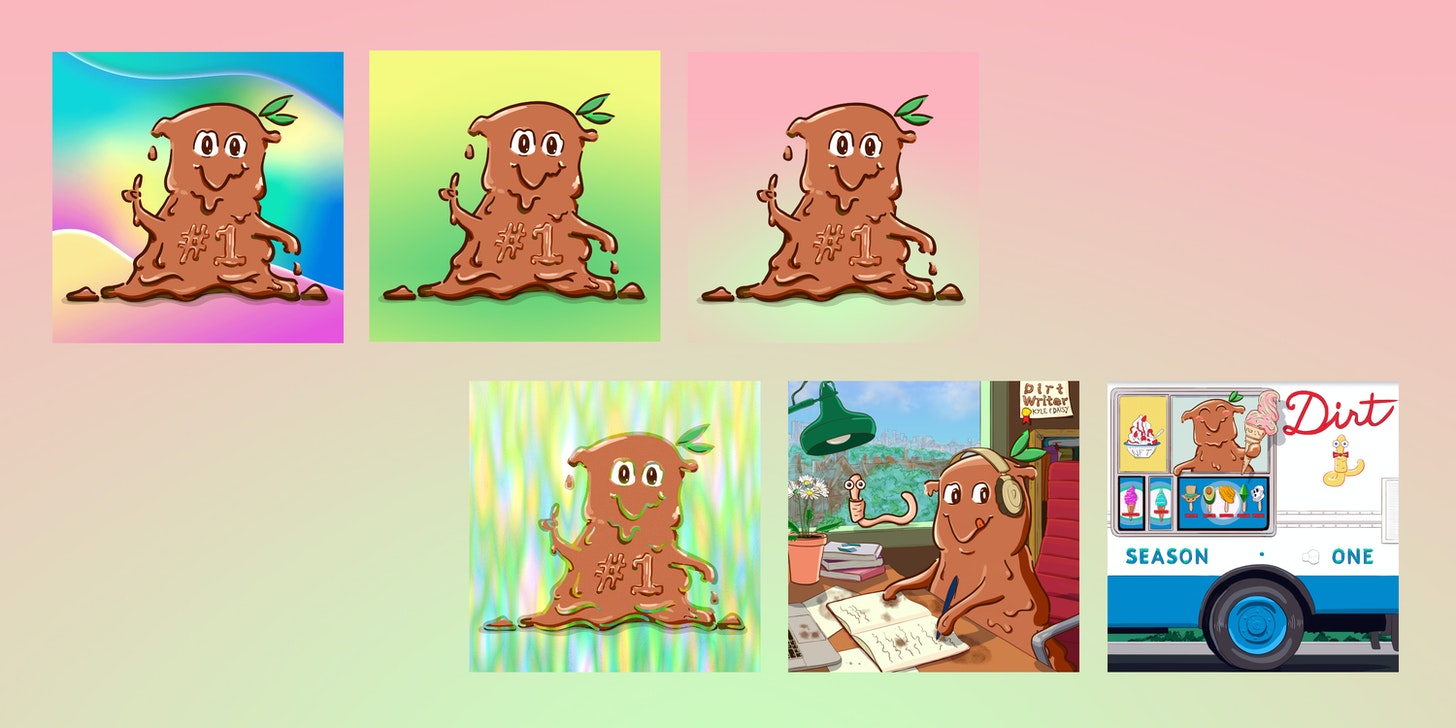

Or, as Dirt explains: “Think of the NFT as your Dirt annual subscription, except it’s something you own (until you decide to sell or trade it)”:

Our NFTs are like digital souvenirs, but souvenirs you can trade, sell, and use to access things like private Discord channels and IRL events. By buying one, you become a Dirt supporter but also an insider, helping us develop the future of the publication. Soon, you’ll be able to use the token to vote on topics that we cover and how we focus our editorial. Think of it as a Kickstarter tote bag but much, much better. Whenever a new reader wants to support Dirt, they can buy one of our NFTs (if there are any left).

“I think NFTs are the newest form of digital content,” Chayka said. “Structurally, that fits with Dirt’s scope.” He first encountered NFTs when he was writing a New Yorker profile of the digital artist Beeple, who had just sold an NFT for a record-breaking $60.25 million.

The first lot of Dirt NFTs sold for around $30,000. They were sold in Ether, a cryptocurrency, and liquidated into U.S. dollars over some time to hedge against the fluctuating exchange rate. This paid for Dirt’s “first season,” which was edited by writer and editor Jason Diamond. (Pieces published before this sale are called the “pre-season.”)

Another set of NFTs is now on the market to fund Dirt’s second season, which is being edited by Alioto. The price is 0.1 ETH, or about $380.71, and so far 21 NFTs out of a set of 100 have been sold — worth about USD $8,000.

(If you’re trying to figure out what Dirt might have made by selling regular subscriptions on Substack instead — it has nearly 6,000 subscribers on its free list. Substack says it commonly sees about 5 to 10% of subscribers convert to paid. So if it relied on a paid subscription model, Dirt might expect to make between $15,000 and $30,000 a year.)

So who’s buying these NFTs? Well, because Dirt is the first media outlet attempting to fund itself in this way, the NFT evangelist community is excited about it (and its potential to make cryptocurrency seem more legitimate to non-crypto-evangelist audiences). NFTs publicly show their owners’ blockchain addresses, which let you see that the owners of Dirt NFTs include not just Dirt readers but also Silicon Valley investors and Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), which are like racehorse syndicates of people pooling their money, but for crypto-products rather than shares of horses. For Dirt’s third season, Chayka and Alioto will set up a DAO where people may be able to vote with their NFTs on what the newsletter should publish.

a trustless media DAO would work like this: Funding exists in a pool, growing via staking or new subscriptions or whatever; writers propose a fee to write a given pitch; token holders vote on the proposal; writer automatically gets paid from the pool when the pitch is approved

— Kyle Chayka (@chaykak) August 18, 2021

Treating contributors well is important to Chayka, who also co-founded freelancers’ collective Study Hall. They’re giving their first 100 contributors each a free NFT. It’s like a “kind of membership card,” Chayka said, adding that he wanted to reward the writers who got in on the ground floor and helped build the newsletter.

The writers don’t all have crypto wallets that can receive NFTs, though, and so the editions of the NFT haven’t all been distributed. Helping contributors set them up has been one of Alioto’s recent administrative tasks — “the least fun and sexy aspect of any project. If it wasn’t tracking wallet addresses it would be managing subscriptions.”

Some of the writers, though, are crypto evangelists, and a handful have accepted payment for their pieces in Ether. One of them is Alex Marraccini, who said she was “initially very skeptical of Dirt’s foray into crypto.” On thinking about it more, she didn’t see cryptocurrency as being any ethically worse than a fiat currency [From the ed: The carbon dioxide emissions generated by cryptocurrencies are one ethical consideration], and being paid in Ether was easier for her for tax reasons — she works for a German employer and pays German taxes, lives in the U.K., but is also a U.S. resident. “This is normally financial hell,” she says.

Contributors are allowed to sell their free NFTs, though none have tried so far. “Hopefully, the [contributors’] NFT is worth something,” Chayka said. Some buyers of the first-season NFTs have flipped theirs for a profit.

This week, Dirt announced a collaboration with London-based magazine The Fence, a young publication known for its satirical takes and serious investigations. It has a print circulation of under a thousand at the moment, but its following includes Alioto, who reached out about doing an NFT collaboration in late August. “It’s much easier to sell something you believe in,” she says.

NFTs are “a super-contemporary way of funding our old-school magazine,” The Fence editor Charlie Baker said. “The problem with British media is that people in this country expect journalism to be free, and there is also little money in advertising for new publications,” which is why trying something like NFTs is attractive to him.

On Monday, The Fence published a British opinion on the TV show Succession as part of the collaboration, and its NFT — called “Filthy” — went on sale on NFT marketplace Open Sea. Sixty percent of proceeds will go to The Fence, 30% to Dirt, and 10% to the artist Mark Costello.

With the growing newsletter environment, more and more writers are thinking about funding model. Chayka isn’t against funding all this with traditional paid subscriptions in the future, if needed — but the NFT model is a nifty idea that’s working at the moment. Chayka thinks that in a year, media CEOs will be asking “How do we feel about NFTs?” For now, Dirt has its answer.

Brian Ng is a writer from Aotearoa–New Zealand, living in Paris.