That sports media struggles with diversity and bias is not new. Just a few months ago, a report from the University of Central Florida’s Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport found that, in the U.S. and Canada, only 19 percent of staff positions in sports journalism are held by women.

But now a longitudinal study looking at bylines across 15 years finds that not only are women underrepresented — they’re not even gaining much ground. And readers aren’t the ones to blame.

Some caveats off the bat: The study only looked at bylines in one newspaper — Munich-based Süddeutsche Zeitung — between 2006 and 2020. So the findings may be generalizable to other outlets or broadcast media. It also focused almost exclusively on soccer. And finally, the study didn’t seem to include nonbinary or trans people in its examination of gender differences.

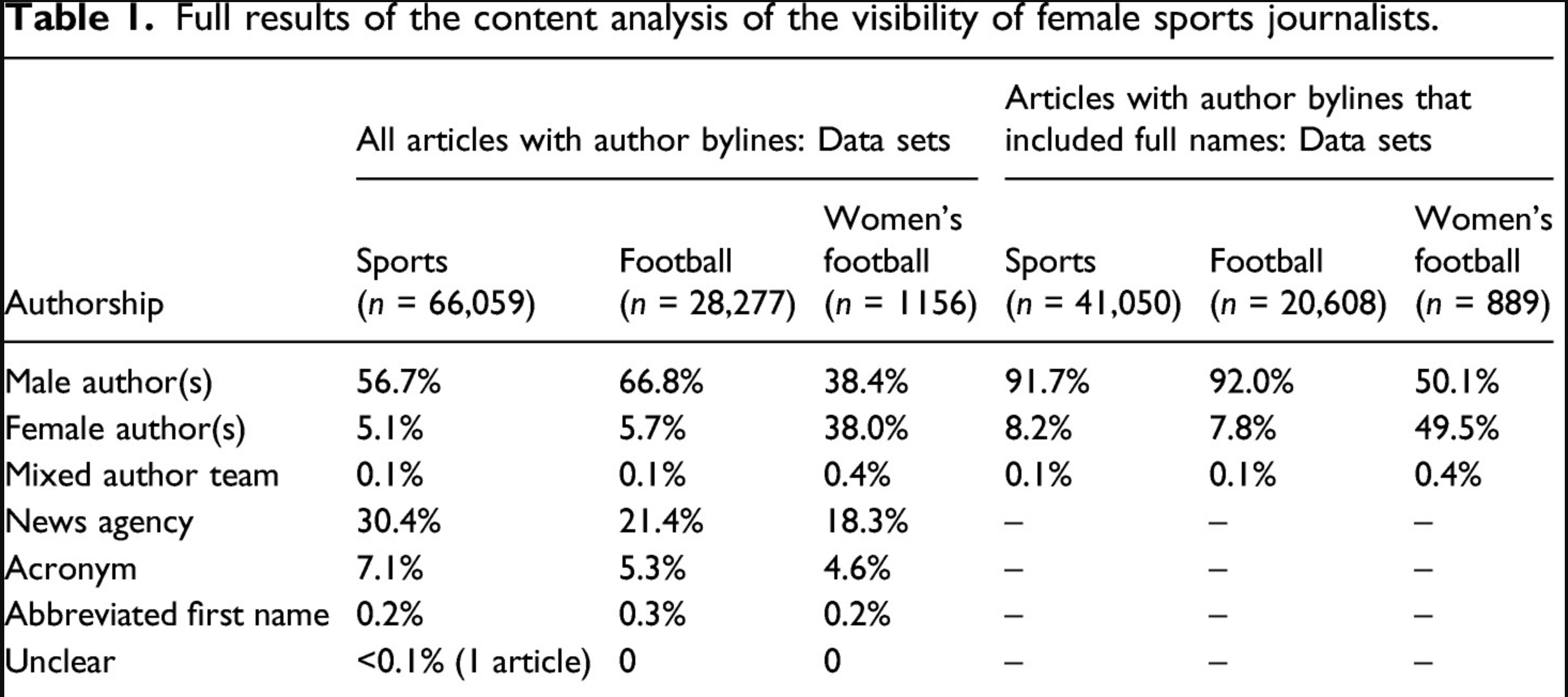

The researchers — Karin Boczek, Leyla Dogruel, and Christiana Schallhorn — looked at nearly 42,000 sports articles published during the study window. They found that only 8.2% of the articles were written by a woman or a team of women. Men wrote nearly 92% of the sports stories, with less than 0.1% of articles having both men and women in the byline.

The numbers were similar when the authors looked just articles about soccer (or, as the Germans call it, Fußball). It was only in coverage of women’s soccer where there was something like parity, with male and female bylines roughly equal.

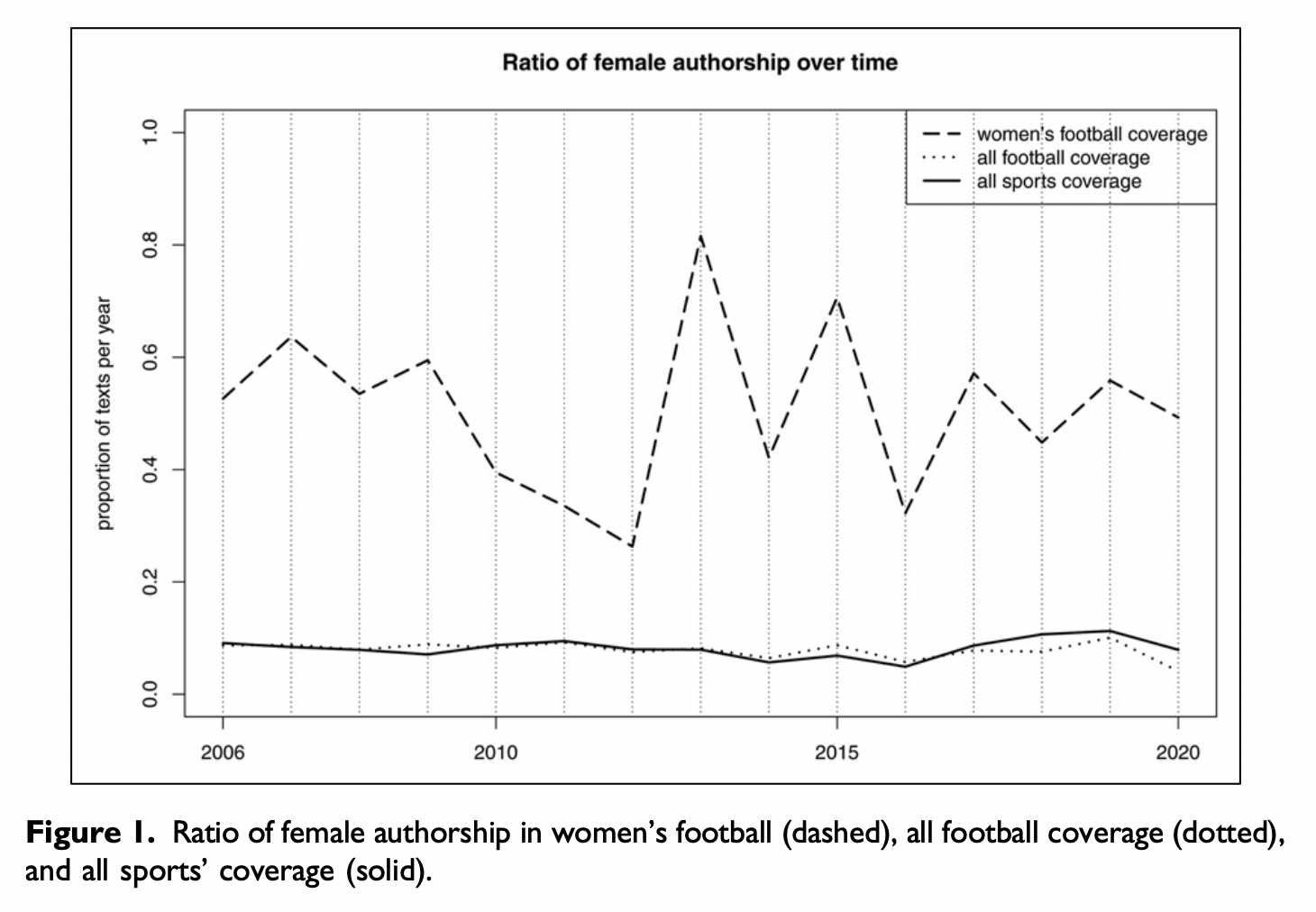

The authors didn’t even find that the numbers dramatically improved over the study duration. The ratio of sports articles written by women hit a low of 5% in 2016 but never exceeded 11% (2019), for a 15-year average of roughly 8%. The same was true for articles specifically about soccer. And even among articles about women’s soccer, the highest proportion of bylines featuring women was 82%, with the lowest at 26%. Overall, that still averaged out to about 50% over the 15-year study span.

So why are sports sections so stubbornly male? One theory holds that it’s the audience’s fault — that readers prefer their sports journalists to be men. The study cites earlier research that found male sports journalists have historically been perceived as more credible and competent by audiences.

The authors conducted a small survey with 635 participants (56% of whom were men). The volunteers were shown a preview of a sports opinion piece. Some were shown the piece with a female byline and columnist photo, some with a male. Some people were shown it as a story about the German women’s national soccer team, some about the men’s. It looked something like this:

Respondents were asked to indicate their interest in reading the article, as well as their perception of the credibility of the story’s author, based only on the information provided thus far. The researchers controlled for variables including interest in soccer, participants’ age, sex and education level as well as affinity for right-wing authoritarian politics (which the authors said has shown to influence gender attitudes).

What they found was that the byline’s gender didn’t have a significant effect — on either a reader’s desire to keep reading or on their perception of the writer’s expertise.

Interestingly, there were differences that hinged on readers’ gender. Women were less likely than men to be interested in a story about men’s soccer — but for stories on women’s soccer, there was no gender gap in interest levels. Women, on average, rated the expertise of female journalists lower than they did male journalists. But men tended to rate the expertise of male and female sportswriters equally.

What does all this mean? Audience perception alone can’t explain the historical and persistent exclusion of women from sports journalism. Readers seem perfectly willing to read and value the work of women sports journalists. The authors call for specific investments in equity — such as the BBC’s 50:50 project — to diversify bylines. “Until changes such as these are implemented across the board, it is likely that women will continue to be invisible and disadvantaged in sports journalism, even if they have as much expertise and competence as their male colleagues,” they write.You can read the full study here.