Public mass shootings — ones that unfold in elementary schools, supermarkets, and parades — tend to receive the most media attention but a new database compiled by the Associated Press, USA Today, and Northeastern University reveals mass killings are far more likely to take place in private homes than in public spaces.

“A guy who kills his wife and children and sometimes kills himself is the most common type of mass killing,” said James Fox, a professor of criminology, law, and public policy at Northeastern University who worked on the database. But “although it is relatively easy to acquire information about the most high profile cases given the amount of press coverage, press briefings by law enforcement, and sometimes even reports from ad hoc investigations, most mass killings receive rather little coverage.”

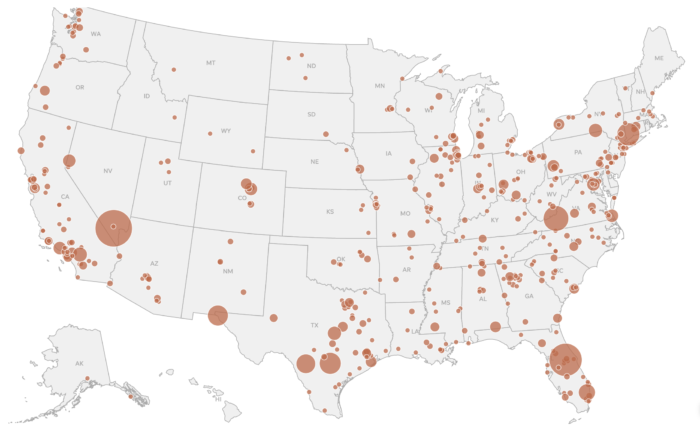

The newly public Mass Killings Database is one of the most comprehensive datasets assembled on the topic. It tracks all U.S. homicides since 2006 where four or more people — not including the offender – were killed. Each incident has dozens of data fields including location and detailed information about the offender (name, age, race, sex, and any previous criminal record), victims (including cause of death and relationship to the assailant), and weapon (including, if applicable, gun type, model, manufacturer, and caliber). The collaborative project has been underway since 2018 and revives an earlier iteration of the database launched by USA Today in 2012.

The architects of the dataset — including Fox and Josh Hoffner, director of U.S. news at the Associated Press — say they hope journalists will use the information to find local angles, add context to important stories, and spot trends. As one example, Hoffner noted that AP journalists used the database after 11 people were murdered at a Virginia Beach government building in 2019.

“We were able to look at the data and identify the frequency of workplace mass killings from the data and tell a more complete story of workplace violence,” Hoffner said. “The data told us that there had been 11 such mass killings since 2006. We hope that type of coverage will repeat itself time and time again by journalists around the U.S. because of the project.”

The dataset is continually updated. (The last update was less than 14 hours before this article published.) That means reporters can get real-time insight into the trend lines of mass killings.

“During the Uvalde breaking news coverage, we were able to immediately add context to the urgent story to say: This was the 14th mass killing at a school since the 1990s and 12th mass killing overall this year,” Hoffner said. “Reporters can now do the same on their stories and break them down in various ways.”

A team of data scientists, reporters, and researchers worked to create the dataset. They began with the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Reports (SHR), which Fox described as having “a rather high error rate” when it comes to mass killings. (The entire state of Florida is missing from the dataset as well as major incidents like the Sutherland Springs church shooting.) In addition, the SHR relies on police records that often list victims injured alongside ones who ultimately died in a single file.

On the other hand, Fox noted the FBI reports proved helpful for identifying cases that did not attract news coverage, including family massacres and gang and drug-related incidents.

The team sought to corroborate each data point with multiple sources and filled in the blanks in the SHR files with extensive searches using internet search engines, Lexis-Nexis, and Newspapers.com. Researchers also regularly contacted AP reporters on the ground for information in their notebooks or to ask them to access relevant court files.

“There are also lots of mass killings (domestic incidents in isolated regions for example) that don’t garner much attention,” Hoffner said. “Those cases require us to do more digging to obtain the relevant data.”

In the days and months following a mass killing, more information becomes publicly available and, ultimately, reflected in the database. Fox said he believes the AP-USA Today-Northeastern database is the only one to include court and sentencing data.

There are other databases that track mass shootings — including ones compiled by The Violence Project and Mother Jones — but the Mass Killings Database includes deaths from the 20% of mass killings that do not involve a firearm.

“Those who are killed with a knife, a blunt object, strangulation, a vehicle ramming, or fire are just as dead,” Fox said. “And even though they do not invoke the debate over gun control, these crimes matter no less just because a gun wasn’t involved.”