What is news, anyway?

I don’t mean to get all metaphysical with you on a Tuesday, but it’s not a question with an obvious answer. What’s news to you might not be news to me. Sometimes, when people talk about “the news,” they really mean “politics and government.” News changes at scale; a new restaurant opening in Zwolle, Louisiana is “news” in a way a new restaurant opening in Manhattan is not. Some news is “hard”; other news is “soft” and often subject to being declared not news at all. Somewhere, there’s a boundary between news and entertainment, but it’s not easy to point at it on a map. And sometimes, the label of “news” implies a certain worthiness, a justification of its request for your attention. (“That story was just a bunch of embedded tweets — that’s not news.”)

These are all important distinctions! The primary discourse around news the past two decades has been about saving it. Something we value is threatened. But even before we get into debates over quality or importance, it’s hard to save something when you can’t even define it.

This is a problem that two academics — Stephanie Edgerly at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, and Missing Conjunctions and Emily K. Vraga at the University of Minnesota — have been poking at in recent years. In 2021, they published a paper, cited dozens of times since, that tried to define the quality of news-ness. The abstract:

A by-product of today’s hybrid media system is that genres — once uniformly defined and enforced — are now murky and contested. We develop the concept of news-ness, defined as the extent to which audiences characterize specific content as news, to capture how audiences understand and process media messages.In this article, we (a) ground the concept of news-ness within research on media genres, journalism practices, and audience studies, (b) develop a theoretical model that identifies the factors that influence news-ness and its outcomes, and (c) situate news-ness within discussions about fake news, partisan motivated reasoning, and comparative studies of media systems.

In the pre-digital world, when access to publishing was limited, news was largely defined by its production. That stuff that gets printed every morning and delivered to people’s houses? That’s a newspaper, and what’s inside it was news.1 It you turned on the TV to watch Tom Brokaw or your local anchors for half an hour, you were “watching the news.” The medium constructed the boundaries of the message.

Edgerly and Vraga defined news-ness straightforwardly: “the extent to which audiences characterize specific media content as news.” But note who has the decision-making authority in this conception: the audience, the readers, the viewers, the listeners. Not the news professionals sitting in newsrooms.

The question of news-ness harkens back to traditional audience theories of media genres and the distinguishing of one type of media from another, yet this classification faces significant challenges from hybrid media. In a world where media blend in unprecedented ways and long-held media expectations have become “unfixed” and “open to reimagining,” do audiences still make assessments of genre, and do such categorizations (if they occur) matter?We argue that media hybridization makes the classification of genres — and specifically the features that lead someone to consider content as more or less news-like — even more important for understanding audience sensemaking and response. With an influx of content and sources available to audiences in the modern media environment, including those that deceptively masquerade as “news,” scholarly research needs to consider when audiences are likely to consider something news and how this label impacts their processing and response…

This conceptual definition has three important components: (a) news-ness focuses on audience rather than producer definitions; (b) news-ness is not a “yes-no” categorical assessment, but one that emphasizes “degree rather than kind”; and (c) news-ness is judged in relation to specific media examples. Together, the concept capitalizes on the “gut feeling” and “mental schema” individuals hold about news. Indeed, past studies have found people are able and willing to render judgments about whether specific examples should be considered news, yet they struggle to provide concrete definitions of news. In other words, news can be difficult to define, but people know it when they see it. News-ness capitalizes on this.

(Ah, the Potter Stewart fuzziness principle.)

I bring up this three-year-old paper because Vraga and Edgerly have just published a follow-up article that aims to examine news-ness in an experimental context. This paper’s titled “Relevance as a Mechanism in Evaluating News-Ness among American Teens and Adults“:

Definitions of news are increasingly fraught in today’s media environment, making audience assessments of news-ness — the degree to which something is considered news — particularly important. Drawing from literature on representation in news and news-ness, we explore how seeing news that features a similar age group affects ratings of news-ness. We also argue that relevance offers as a psychological mechanism to explain how audiences make assessments about news-ness.Using two experiments among teens and adults in the United States, our results confirm that proximity (in terms of age) of the groups represented in news affects audience evaluations of news-ness, with relevance acting as a mediator to linking proximity and news-ness. These results are replicated across issues and among American teens and adults. We discuss the importance of representation and relevance as strategic initiatives to involve people in news.

The question here is, again, an important one. If anything has rivaled “saving” the news as a nexus for discourse, it has been diversifying the news — in terms of who produces it, whose stories it considers worth telling, and which audiences it chooses to seek out. Does representation in the news people see make them more likely to consider it “news” — or even to grant it some sort of elevated mental status as important, or maybe even worth paying for?

(Aside: Pew is out today with a survey of Black Americans’ perceptions of the news media, and it lines up awfully well with the thesis here. The high points: “Most say that Black people are covered more negatively than people in other racial and ethnic groups. Black Democrats and Republicans, as well as Black adults across all age groups, are similarly critical of news coverage of Black people. Educating all journalists about issues impacting Black people and history is among the steps Black Americans say would help the situation. Many Black Americans say Black journalists are better at understanding them and covering issues related to race, though few see a reporter’s race as a key factor in determining the accuracy of news in general.”)

Instead of race, though, Vraga and Edgerly look at the fissures of age — specifically, young people. Teenagers and young adults have famously different media consumption patterns than those middle-aged or older. Ask them and they’ll complain about not seeing their lives reflected in the mainstream media — or, if they do, they’re often filtered through a catastrophizing lens of parental worry. (“Is your teen about to ruin his life with this hot new TikTok challenge? We’ll tell you at 11 o’clock.”)

Their experiment was designed to evaluate two related but distinct concepts: news-ness and relevance. A story can be undoubtedly newsy but not feel relevant to the reader’s life. (See: Ukraine, Syria, most international coverage.) Or a story can be highly relevant but not especially newsy. (See: “Answer These Five Questions and We’ll Tell You Which SpongeBob SquarePants Character You Are.”) But how do those qualities influence each other?

Vraga and Edgerly picked two broad subjects — mental health and money — and came up with stories about each they thought aligned with different age groups. Money stories were either about student loan debt or retirement savings; mental health stories were about either depression or Alzheimer’s.

Those surveyed — 800 teens (ages 13 to 17, average age 15) and 786 adults (ages 18 to 92, average age 45) — were each shown a screenshot of a fake Associated Press story with one of these four headlines. Each of them is bad news, but bad news primarily directed at cohorts of different ages:

New study finds that depression diagnoses among younger adults increased from 2017New study finds that student debt and default among younger adults increased from 2017

New study finds that Alzheimer’s diagnoses among older adults increased from 2017

New study finds that retirement savings among older adults decreased from 2017

Then people were asked four questions about the story, on a seven-point scale: Was this post “definitely not news,” “sort of news,” or “definitely news”? Was it a good example of news? Was it what I expect news to be? And was it not very news-like? Then there were two questions on relevance: How relevant was the post to you? And did it mean a lot to you?

They found that, among teens, the stories that focused on teen-adjacent issues (college loans and depression) were rated significantly more relevant (about 0.7-0.9 higher on that seven-point scale), not only a little bit more news-like (about 0.2 higher). They also found that increased relevance correlated with increased perceptions of news-ness.

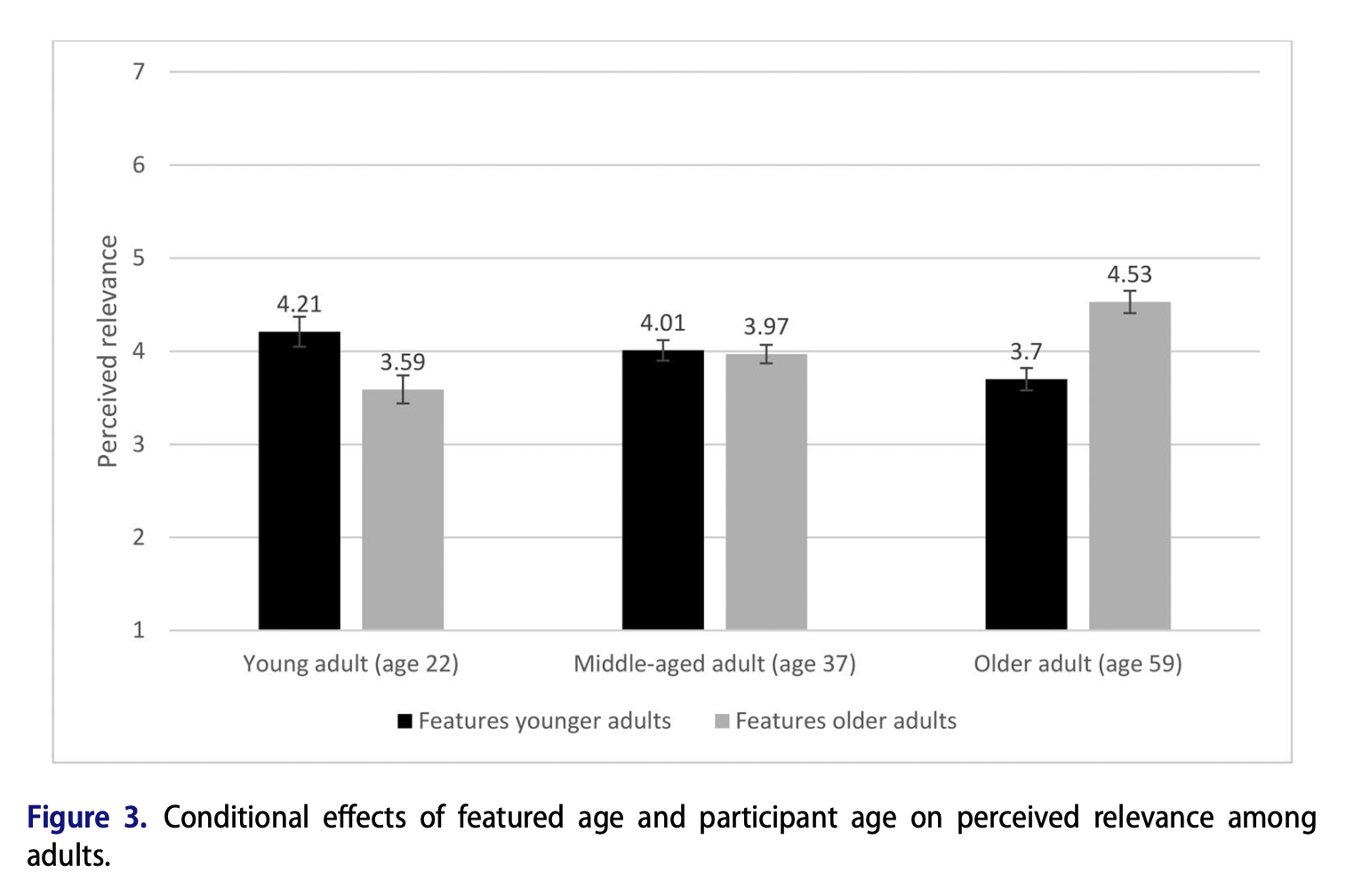

What about the older sample? First, adults are not a monolith: Twentysomethings saw higher relevance in the teen-adjacent headlines than Baby Boomers did, and vice versa for the headlines on Alzheimer’s and retirement. Second, adults were more likely to see all headlines as news-y, no matter what age group they’re about. Relevance seemed to support news-ness among the adults much as it had in the teen sample.

This model demonstrated that there is a significant negative indirect pathway for younger adults — with exposure to a story headline featuring older adults (as compared to younger adults) producing an indirect negative effect on news-ness via lower perceived relevance. This pattern was reversed for older adults: seeing a story headline featuring older adults led indirectly to higher news-ness via perceived relevance. There was no indirect effect on news-ness for featured audience for middle-aged adults, likely because they reported no differences in the perceived relevance of the headline…Our results demonstrate seeing a featured group in a story headline that is more proximate to an individual creates higher perceptions of the relevance of the story, which then translates into higher ratings of news-ness. This finding occurs similarly for teens, for younger adults, and for older adults. Middle-aged adults see the story featuring younger or older adults as equally relevant — but the link between perceived relevance and news-ness operates similarly for this group as well.

At one level, any decent editor could have told you the basic takeaway here: People find news about people like them more relevant than news about people who aren’t. That’s probably been true as long as Homo sapiens has been hanging out in groups. But it does contribute a business case to debates over diversity in the news. It’s not just the ethical choice to represent a wider swath of your audience — it’s also the strategic choice.

Thus, audience evaluations resemble journalistic decisions about newsworthiness — proximate stories hold greater news value because they are more relatable. Our findings support this long-standing journalistic belief by linking audience perceptions of relevance and news-ness…More broadly, our findings also have practical implications for news production. Research has identified failures on the part of news organizations to ensure that all groups see their concerns included and legitimized in news coverage. While such coverage has many benefits to society, we add a self-serving benefit: this study suggests that seeing a proximate social group encourages people to see the content as higher in news-ness. Recent research has highlighted the disconnect between teen and young adult audiences with news organizations.

Our study showcases one way of narrowing this gap — by publishing stories that feature people “like” the audiences. The disconnect many young people feel may come from a lack of representation, which we show violates a fundamental aspect of how audiences — teens and adults — define what is news.