There was the voice of Jon Miller, baseball’s best and wittiest game caller, setting the scene for me, some 5,000 miles away from San Francisco’s AT&T Park. As Travis Ishikawa strode to the plate, my Shinkansen bullet train was headed north out of Kanazawa, Japan — quite ironically, the seat of Ishikawa Prefecture. As Ishikawa powered a home run to the deepest part of the ballpark, winning the game with a walk-off and sending the San Francisco Giants to the World Series, I heard live the fan euphoria, and the familiar voices of the Giants’ radio crew picking apart the pivotal plays of the game.

It seems like magic — but it’s just radio, pushed beyond the ionosphere by the Internet, with the help of some of the 500 tech people employed by MLB Advanced Media.

Chuck Richard, my friend and Outsell colleague, and I rhapsodize about MLB.com. We enjoy it as baseball fans. “Let’s say you’re a Red Sox fan living in New York — you can listen to the local Boston broadcast from WEEI with Joe Castiglione every night,” Chuck says. “When you’re a Red Sox fan flying home from Brazil in October 2013, during the exact time of the clinching game in the World Series, you can use the American Airlines on-plane wifi to listen to the game live at 35,000 feet. Now you can see the strike zone with every pitch of every game to see whether the ump got it right using the PITCHf/x data that MLB funded the development of and installed at every stadium. Now the FIELDf/x defensive digital tracking stats are beginning to show up.” (Bob Bowman, president and CEO of Major League Baseball Advanced Media, or BAM, explains the “revolutionary” innovations to Grantland.)

Along with our fan exultations, we’ve noted the digital smarts inside the MLB products, and how their innovations could apply to publishers of all types. So today, in the midst of the World Series, let’s focus on what MLB.com does so well, and what news publishers can take away from its leadership. Let’s especially focus on its success in mobile — probably the area of greatest challenge and opportunity for publishers today.

Major League Baseball launched MLB.com just 12 years ago, to mild derision and deep suspicion about the idea that a sport league could cover itself well enough to win a major audience. MLB.com has done that and more. Its numbers are impressive:

One secret of innovators like MLB and Pandora is early investment in new tech — before the opportunity is universally apparent. Back in 2005, Bob Bowman made his first investment in mobile, hiring two staffers. That was pre-app, pre- the time we thought about an age of mobile majority. Today, about 500 of its total staff of 750 do tech, and 60 or so work on mobile alone. That’s how you optimize experience across those 400 devices. About 100 fill out the editorial staff, including 30 beat writers (one for each team) and a growing roster of columnists.

MLB.com, of course, is only part of how the web changed baseball coverage. Long the semi-exclusive province of daily newspaper beat writers and columnists, along with a handful of national magazines, it’s been democratized. ESPN, of course, is a major player. Further, ESPN’s Grantland, Gawker Media’s Deadspin, Vox’s SB Nation, and Turner’s Bleacher Report lead a parade of decidedly unofficial sites, offering an alternative to MLB.com’s very civil approach to a boisterous sport, with often highly spirited, sometimes profane voices. MLB.com does host some good and strong MLB Voices — including former newspaper columnists like Richard Justice, Tracy Ringolsby, Hal Bodley, and Mike Bauman – though sometimes they’re harder to find than they should be.

One reason those columnists may be harder to find: MLB.com is about the day-to-day flow of the game. Fans pay their money, and they get a steady stream of baseball basics. Many think of it as a utility. In part, that’s because it’s monopoly of a sort, the league presenting itself and, of course, controlling video rights. As Chuck Richard points out, though, it’s an ususual monopoly. “We can give MLB Advanced Media some well deserved credit. Most other monopolies, including utilities, telephone companies, cable companies and governments, have never developed diddly squat online.” We can also give the league credit for its self-acknowledged ownership position — the tagline “This story was not subject to the approval of Major League Baseball or its clubs” runs at the bottom of every story — though it does seem to remind us too much of the box in which journalists color. One lesson, though, says Richard, “Some will do self-coverage better, more journalistically, than others.”

We come this week, though, not to just celebrate the National Pastime and MLB.com’s digitization of it, but to ask how to learn from this pioneering model. If MLB can serve as the official town crier of baseball, serving its village, how can newspaper-based and local broadcast-based companies take pointers from its impressive scorecard?

Even before MLB.com embraced mobile and streaming, its web product excelled. It is, though, its smartphone and tablet products that offer best-practice models for publishers and product creators. Let’s quickly breakdown what works so well, and may be applicable, about MLB.com.

Customization. Where does a fan want to start? With her favorite team, of course. It’s a snap to pick one or several teams, and the top one becomes the home page.

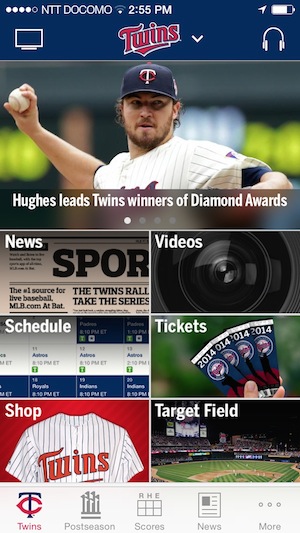

Customization. Where does a fan want to start? With her favorite team, of course. It’s a snap to pick one or several teams, and the top one becomes the home page. Fit and scale. The longstanding publisher cry: How can we possibly fit what we need to on such a small screen? Check out the MLB iPhone screen, which offers that small real estate. In the stretch of four diagonal inches, fans see much choice. On a team page, everything from news and video entry points to schedules, tickets and shopping are right there. On a game page, the multiple choices range from story wrap and box score to video highlights and inning-by-inning scorecard, with useful persistent navigation at the bottom of the screen. It would seem to be a lot to fit on one screen, but it fits well.

Fit and scale. The longstanding publisher cry: How can we possibly fit what we need to on such a small screen? Check out the MLB iPhone screen, which offers that small real estate. In the stretch of four diagonal inches, fans see much choice. On a team page, everything from news and video entry points to schedules, tickets and shopping are right there. On a game page, the multiple choices range from story wrap and box score to video highlights and inning-by-inning scorecard, with useful persistent navigation at the bottom of the screen. It would seem to be a lot to fit on one screen, but it fits well. Data-friendly. Baseball fans love data — we just call it stats. The wonkiest numbers can be a swipe away, an extension of a story – or a lead-in to it.

Data-friendly. Baseball fans love data — we just call it stats. The wonkiest numbers can be a swipe away, an extension of a story – or a lead-in to it.How can publishers take all those advances and apply them to their own businesses?

Baseball is a passion, but it’s also a big village. It’s a group of people with shared interests — and shared information needs and enthusiasms. News companies serve many villages, some geographical, some topical.

Let’s take one opportunity and challenge that CJR gave an excellent airing last week: the kind of election and endorsement information and opinion that local newspapers used to routinely supply in print. Writer Anna Clark pointed to good experimentation here and there with forums and video, and one editor said he’d love to produce an a robust online voters guide, but couldn’t afford the resources.

Apply the MLB.com model here, and we see a template of voter access impossible in the pre-digital age. In fact, the creation of a video-friendly, interactive-enabled, story-and-picture toggling, archives-accessing template could be done once (calling Jeff Bezos or the Knight Foundation) and filled to perfection across the country.

Or take another topical area that many local newspapers used to excel in: music coverage. Again, it’s pictures, video, and stories, and a good amount of data. Templatized, it becomes a great mobile experience on its own and a further model for other arts and entertainment coverage.

Finally, let’s consider the local or hyperlocal conundrum. Since AOL reduced and jettisoned Patch, we haven’t heard as much about local news. In part, that’s a resource allocation question for dailies. Yet given the run of news from metro- or city-wide to neighborhood news — news that runs through a print paper and haphazardly on websites – it’s as much an organizational issue. Think of “the paper” again as a utility, as many readers do. It’s a daily compendium of stuff. Increasingly, if fitfully, in the digital age, it becomes a storehouse of relational, retrievable data. Replace the team metaphor of MLB.com with that of an area or neighborhood, and consider how a new organization of local content can unlock much value for the reader. Here, as in music or politics, the time-travel, bring-archives-alive dimension profoundly advantages those who have published for decades or centuries.

White-boarded, MLB.com-adaptive brainstorming is particularly timely for companies like Gannett and Advance, which are thoroughly re-thinking traditional beats. The beat, and its coverage, is one thing; the presentation of the beat will equally important.

Real multimedia – so long promised, now technologically easy – has proven to be a tough exercise for legacy publishers. Ironically, former newspaper journalists — including Dinn Mann, top editor and executive vice president of MLB Advanced Media and a Kansas City Star alum — invented MLB.com. They’ve paved a way. Now can publishers and journalists follow, not needing to invent, but simply to borrow and innovate?